REVIEW: Fall for Dance North’s 11th edition opened with a meditative solo, a tsunami of an ensemble piece, and a smoky Harlem-meets-Havana jam

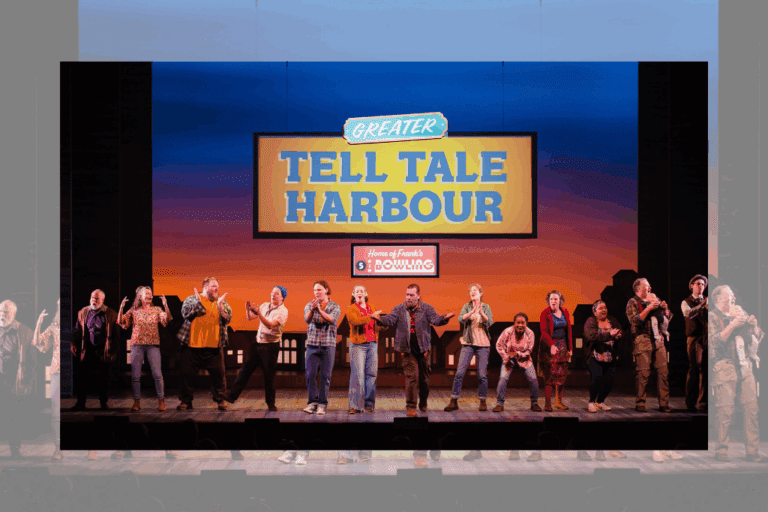

Last Wednesday at the Bluma Appel Theatre, the 11th edition of Fall for Dance North descended on the city with renewed energy. This year’s two-week festival — known for bringing emerging and established dancers from around the world to Toronto with how-could-you-not priced tickets — marks the first under new co-CEOs Robert Binet and Lily Sutherland. Their programming feels fresh and ambitious.

In addition to the three signature mixed programs put on in collaboration with curatorial fellow Esie Mensah (who’s a big reason for this year’s rich range of styles), there’s performance art programming at The Citadel that offers front-row-only seats, a two-day closing party at OCAD’s Great Hall with six chances to see an assortment of approaches all in one room, and adjacent free workshops for all levels led by Rock Bottom Movement director Alyssa Martin and visiting artists.

The first program on opening night offered three Afrofusion works: Duende, a meditative solo by London-based Dickson Mbi; Mensah’s own ensemble piece ESHI with students of Canada’s National Ballet School; and New Yorker Sekou McMiller’s smoky, Havana-meets-Harlem jam Afro Latin Soul.

The evening began with an empty stage, blank as a canvas with one spotlight illuminating its centre. Mbi entered the circle of light at a glacial pace, foot first, articulating every bit of heel, arch and toe, while a subterranean synth throbbed. As the music picked up, he folded and tumbled through lunges and Graham-style floorwork, punctuated by brief bursts of athleticism that stopped after only a few counts — as if he’d startled himself out of his own reverie.

Given the title Duende is an impish spirit in European and Filipino folklore that also translates to “duelling” in Afrikaans, I expected a stronger sense of struggle or a cautionary tale. Instead, I felt that central tension was slightly underdeveloped, with relatively safe choreographic choices that could have been filled in with a deeper sense of turmoil or storytelling. That said, his control and musicality were mesmerizing, and saw their peak in moments when flicks of his fingers matched the strings while expansions of his chest echoed the drums.

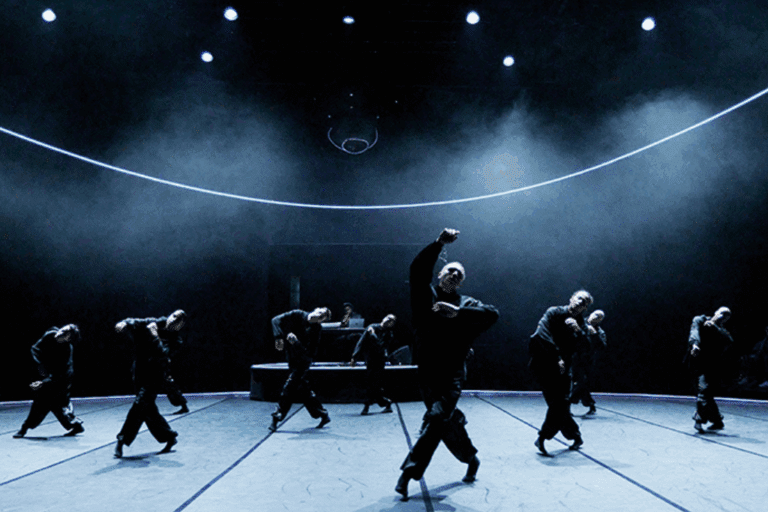

After brief remarks from Binet and Sutherland, ESHI opened on an aquatic blue-lit stage to honeyed R&B tunes by Yohance Parsons and Joanna Majoko. Mensah appeared hunched and haunted, soon joined by a corps of 19 ballet students who appeared to be embodying grief’s many currents.

“Eshi” means “water” in the Ewe language of Ghana, and the dancers pooled into tidal stage pictures, with Mensah always at their centre, being carried or washed by them. These images of grief were moving but sometimes too literal. For me, the most arresting moments came when the dancers faced the crowd in strong poses — their arms or knees bent at sharp, 90-degree angles — and spring-loaded emotional energy that signalled the active fight for closure.

After intermission came Afro Latin Soul, a full-swing immersion into a 1940s New York City jazz club. A live band warmed the back of the stage as McMiller, in a cream suit and saddle shoes, and a lav mic that dangled from an unfortunately loose cord. As the band played softly behind him, he grooved and announced muffled phrases to the crowd as the mic bounced on his belly, catching broken snippets like, “Afro Latin” and “is for the people.”

The piece cycled through solos — a tapper’s witty duet with a drummer, a flirtatious jazz interlude — but found its power in mambo ensembles. Their snappy syncopation and lightning-fast footwork crackled electricity, thanks in part to Teresa Garcia, who had me trying to keep from blinking so I could catch her every hit. When the choreography loosened into improvised dance circles, the energy waned, but McMiller brought it back with an infectious communal finale, inviting the previous dancers back on stage and the crowd to stand up, clap, and sway.

In each piece, the choreographer was a central presence. For Mbi, self-performance was the point, but Mensah and McMiller, both mentors, shared the stage with younger troupes. In ESHI, I wondered why Mensah hadn’t given one of the young dancers the leading role; I wonder if this piece was a way to teach her students the shape of grief. When I mourned for the first time as a young adult, I had no reference point for the experience, and I suspect many of the students are likely too young to have experienced deep loss just yet. Perhaps having Mensah at the centre of ESHI was an act of guidance for the future — a model for how to endure bereavement for the dancers to look back on and a reminder of the somatic power they hold to move through emotional tides.

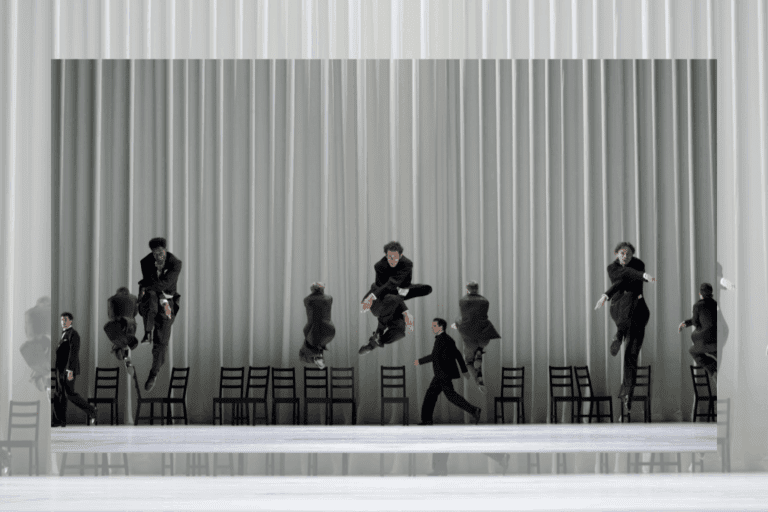

If opening night is any indication, this year’s Fall for Dance North will deliver on its reputation for range and vitality, reaffirming how inclusive, diverse, and uncontainable dance in Toronto can be. The second program, shown over this past weekend, included one of my favourite contemporary ballets, Reverence, by Ethan Colangelo with dancers from the National Ballet of Canada, and a world premiere of echos of the same tree by Ambrose Tjark & Kwasi Obeng Adjei.

The final program promises to end the festival with a bang, bringing eastern and western traditions together with a rare visit from the Royal Ballet, who will perform sections of Swan Lake and Winter Dreams, paired alongside another world premiere: Shanaasai, a romantic Kathak duet by Tanveer Alam.

The Fall for Dance North Festival runs at various venues across Toronto until October 26. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments