Fringe: Memories of a Long-Time Volunteer

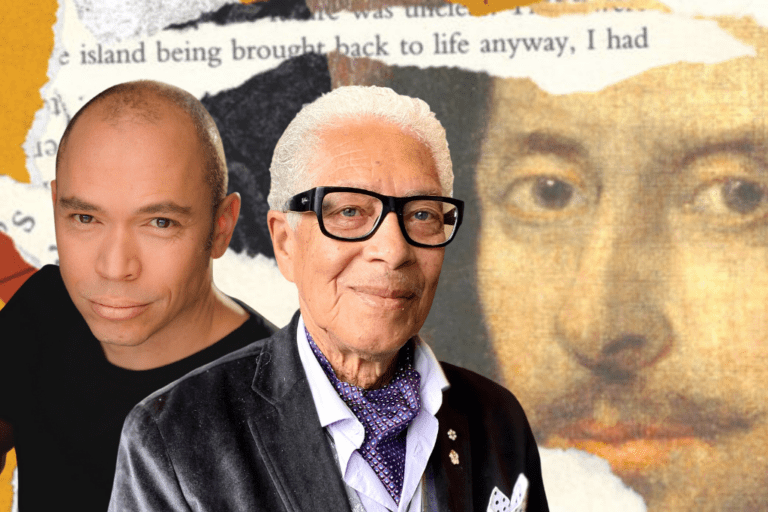

Archival images by Gregory Nixon and courtesy of the Toronto Fringe

My introduction to the Fringe was when I was asked to volunteer. At the time, I had already had several years’ experience volunteering at not-for-profit theatres: beginning with Theatre Plus Toronto, Tarragon, Factory, and Theatre Passe Muraille. It is odd that I hadn’t really known that the Fringe existed to prior to that request, but it has been an important part of my life ever since. Thank you, Sandra Hodnett. I now volunteer at perhaps a dozen theatre companies and festivals and am grateful for every opportunity and for the friendship of every person I have met as a result.

What follows are my memories, my perspectives, and my recollections of my Fringe experiences, and thus may contain but are not limited to accurate depictions.

When I first became involved with the Fringe, the amazing and wonderful Nancy Webster and Linda Keyworth were in charge. Nancy’s tenure as Fringe Producer occurred early in her career. She has had a varied career in arts administration, has won several awards as a result, and is the current Executive Director of Young People’s Theatre. Linda, Fringe General Manager, was also in the early stages of her career, which has more recently taken her to production management in the film and television world. Even though I didn’t know them back then, I found them welcoming, approachable, and friendly, always showing their appreciation for volunteers and others involved with the Fringe. They served directly after the originators of Fringe, through the bulk of the nineties.

The Fringe lottery party tended to happen in February, usually on the coldest day of the year and often in the draftiest venue. We volunteers were stationed by the cold entrance to welcome those hoping for a slot in the Fringe. We would look up their assigned Fringe numbers from printed lists, write the appropriate number on a tiny scrap of paper, and hand it to each applicant hoping to hear that number called. Prior to the draw, and to ensure the integrity of the process, cards with numbers eligible for each category were counted by an arbitrary attendee who then wrapped an elastic band around each category’s bundle and signed and attached a paper on top of the pile to confirm all the numbers were included. This kind of legal audit currently also continues to prove everyone entered has an equal chance to be drawn. When it is a category’s turn to be drawn, the bundle is shown to the person who checked and signed it to prove no tampering with the bundle has occurred, then the elastic is cut, and the cards drop into a bin which is then covered and shaken (but not stirred). Various individuals then draw and call the numbers. In the early years the selected cards were inserted into slots on a board, whilst in later years they were projected from an overhead. A couple of people were assigned to write the selected numbers on a chart as an official record of the companies drawn in each category.

Back then, the Fringe began on a Thursday early in July and ran for ten days. All of the shows were in University of Toronto theatres, within walking distance of each other (I was rather mobile then so even I could manage the walks relatively easily). There were a few BYOV (Bring Your Own Venue) productions nearby, too (but the venues usually stayed where they were, and we brought ourselves to them). Often those productions were played outdoors at the mercy of the weather.

I remember one volunteer shift at Central Tech where we waited at the top of the stairs under the overhang to see if the show would be able to go on. But alas, it had to be cancelled. I did, however, meet some people there whose careers I have followed since. That’s a bonus of the Fringe experience: watch people early in their careers and follow them as they progress, and then see other people in other shows and follow their careers, and so on. And I was able to see that rained out show at a later performance. It was terrific.

The House Managers and the volunteers used to construct and put up the tents at each venue, as they came unassembled (the tents, not the House Managers and volunteers). The House Managers had to receive training on how to put them together properly because it was so cumbersome and complicated. Nowadays, they still assemble the tents, but the newer tents come with their poles already inserted and just need to be pulled open, stabilized, weighted down, and closed again at night. We would also bring out tables and chairs along with boxes of Fringe and show programs, plus pre-written signs with rules, reminders, and information. We printed the day’s schedule of performances on white boards with water soluble markers in different colours and wiped them clean at the end of each day. If the wrong kind of marker was used, vestiges of them remained on those boards forever. Then we counted floats, ensured we had enough of the right change, and secured weights and rocks to keep everything from blowing away. If anything did decide to blow away it would almost always do so at the most inopportune moments. (Tents can still blow away on a windy day—last year on a particularly windy day, a tent positioned in front of the Randolph Theatre blew across Bathurst Street. A couple of kind passersby caught it on the east side of the street and held onto it until my fellow volunteer and the House Manager rescued it and set it up again—with additional weights to encourage it to stay put. I did my best to keep everything else on the table from blowing away. Later that same windy day, the other House Manager rescued an errant five dollar bill). After the last show of the day was loaded in, the whole procedure happened again in reverse, and everything was stored inside the venue for the next day.

Prior to the Fringe run, some of the volunteers would come to the tiny Fringe office to collate and fold copies of The Harold—the Fringe newsletter—to mail out to roughly three thousand recipients, informing them about the upcoming festival. (I believe we mailed newsletters at least one other time during the year and the process was the same). We stuffed them into envelopes upon which we pasted addressed labels. We sealed the envelopes, applied stamps, and put them into boxes so they could be mailed. We had different boxes for different postal codes to make it easier for the Post Office to get them out more quickly than if they had to sort them from scratch.

It was very exciting in later years when the stamps came on rolls with their own adhesive backing, and the envelopes, too, so we didn’t have to use the “lickers” anymore. Before they came with their own adhesives, we had had to turn over these little bottles filled with water and apply the wet spongy tops to the gluey part of the flaps on the envelopes and the backs of the stamps. It was often messy and sticky, because the bottles were too full at first and water would spill out, but we made it work. The camaraderie of those sessions made them fun, and some of us are still friends today (another bonus).

During the festival itself, bicycle couriers would deliver the daily-except-for-Tuesdays Harold newsletter, printed on different coloured paper each day, with information about changes, funny stories from House Managers and Technicians (still miss those), and various tidbits, short articles, and of course, Marty Koven’s haikus. The couriers also delivered change, notices, and other items and picked up money and other stuff which they took to the festival office at the Tranzac.

Tickets were only available at the venue box office beginning an hour before each show. We accepted the money (I remember eight dollars being the norm then, so making change could be challenging to the less than mathematically inclined), handed out the tickets, indicated where people were to queue, and emphasized the familiar “no latecomers will be admitted policy.”

It was crucial that every show started and stopped on time to keep on schedule, hence the no latecomers policy. The maximum length of a show was sixty minutes and that was strictly enforced. In the thirty minutes between shows, the audience had to leave lickety-split, the outgoing show had to remove their set, and then the incoming show had to put theirs up. Depending upon how speedily this happened, we usually had about five minutes to load in the audience (and for audience members to use the loo—which also could be used briefly after the show, same as nowadays; the routine for attendees continues to be queue, view, loo, and repeat). Even if someone was the dying aunt who came from Australia on the last day just to see the show, House Managers had to enforce the policy. Volunteers, like House Managers, have probably heard every potential excuse by now about why that person was so special they needed to enter late: from not being able to find a parking spot because they were at a premium that day, to not paying attention to what time the show was scheduled to start or at which theatre it was being performed. (It won’t start over again like a movie? You mean there are shows in different theatres? You mean the venues are not next door to each other?) Being stuck in excessive traffic whether they were travelling by car or TTC was a favourite excuse, as if that was the only day ever in which everyone was on the road so they didn’t know to leave plenty of time.

Other volunteers would work at the Fringe tent and some also helped with set up and take down. Some tallied the ticket receipts so the performers could be paid. There were many duties for volunteers but I don’t know if I have remembered all of them (or if I even knew some of them were happening).

I have asked a few volunteers for their comments about how they heard about the Fringe and to share their memories of volunteering. A few have had some similar experiences to mine. I’d love for other people to provide their memories too.

Valary Cook: “I can’t remember how I heard about the Fringe, but I loved the idea of the unexpected in performances and the opportunity it offered for so many aspiring artists to be seen … and make some money! Some assorted memories: seeing Kim’s Convenience, and The Drowsy Chaperone as Fringe shows; being in the Tarragon the night of such a huge rainstorm that several Fringe venues lost power and had to cancel, but our shows went on as the rivers of water pour down Bridgman. I think my favourite is being at a Canadian-themed satire show that referenced Ian Hanomansing and while we were singing “Ian Hanomansing he’s so handsome” realizing he was standing right behind us—he’d come from Vancouver to see the show!”

Larry Lubin: “I don’t remember when or how I heard about the Fringe. It must have been late 80s or early 90s. I started volunteering in the late 90s. I love working at the Fringe because of the opportunity to meet and talk with other theatre lovers, but the funniest stories are the ones about latecomers and their attempts to enter the theatre after the doors are closed. The striptease and dirty dancing one is my favourite.”

Eleanor O’Connor: “Volunteering for the Fringe changed my life. When I was working full time, I thought I was a regular theatre goer. I had a subscription at Tarragon and Canadian Stage, went to Stratford and Show … Then one July we were in town and I discovered Fringe. Then I learned they needed volunteers. I volunteered. Then I volunteered other places. Through that experience, I made a whole network of new friends. My new friends alerted me to must-see shows, and I discovered the world of indie companies in Toronto. Many performers whom I saw for the first time I now follow almost religiously. Many companies I wasn’t aware of have become must-sees. Perhaps the best thing Fringe did was make me more comfortable going to the theatre alone. Now I see at least 3 shows a week, and I almost always run into someone I know.” Computers have changed many aspects of the Fringe, particularly our being able to purchase tickets in advance. I have mixed feelings about some of the changes—although of course change is inevitable if organizations are going to survive and thrive. I understand the decisions to make ninety minute show slots available, to increase the number of shows, and thus to expand the number of theatre venues used by Fringe. However, the law of diminishing returns comes into play, and many potentially worthwhile shows are lost in the shuffle. The difference between shows that used to be under the BYOV banner and the current “site-specific” designation is tenuous at best. I like that activities are now offered at the Kids’ Venue, although I must admit I miss the George Ignatieff Theatre as a regular venue.

Computers have changed many aspects of the Fringe, particularly our being able to purchase tickets in advance. I have mixed feelings about some of the changes—although of course change is inevitable if organizations are going to survive and thrive. I understand the decisions to make ninety minute show slots available, to increase the number of shows, and thus to expand the number of theatre venues used by Fringe. However, the law of diminishing returns comes into play, and many potentially worthwhile shows are lost in the shuffle. The difference between shows that used to be under the BYOV banner and the current “site-specific” designation is tenuous at best. I like that activities are now offered at the Kids’ Venue, although I must admit I miss the George Ignatieff Theatre as a regular venue.

But I’m glad of what hasn’t changed: the people. Seeing up-and-coming and previously-unknown-to-me artists, as well as more established ones, perform and take calculated risks is thrilling and a joy. Meeting and reuniting with staff, volunteers, artists, and audience members, too. I love all of it.

The Fringe Collective, presented by the Toronto Fringe, runs July 1-12 on the Fringe website. For more information, tickets, and access, click here.

Comments