REVIEW: Guilt sends Diane Flacks on an odyssey of culpability

If you could sum up your life in a feeling, which would you choose?

For me (and my tendency towards sentimentalism), it would probably be nostalgia. Others might pick love, or ambition, or despair.

For actor and theatre creator Diane Flacks, that feeling is guilt. Thorny, inescapable, shape-shifting guilt.

Flacks attributes this thread of her life to a few sources — to her status as a relatively well-off white woman in Toronto, perhaps, or to her Jewish heritage. Guilt isn’t just a feeling to her: it’s both a companion and adversary as she navigates her life, making choices that in the end will either amplify or quell the relentless culpability sitting on her shoulders at all times.

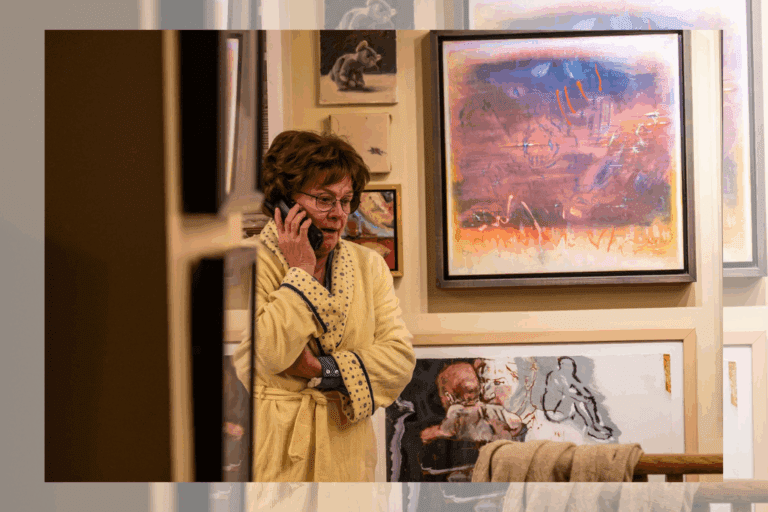

In Guilt, Flacks’ solo show in its Toronto premiere at Tarragon Theatre, we follow Flacks on a series of becomings, watching her evolve into a mother, and eventually, a divorcée. That second one in particular seems to stir up the strongest feelings of regret and heaviness — her divorce is the painful ending to a story of falling out of love, a breakup tangled with infidelity and parenthood. Flacks doesn’t cut herself any slack in her recounting of what happened — while, no, it’s not all her fault, she tells us, it’s not not her fault either — and the result is a 70-minute play drenched in honesty, pain, and even humour.

There’s lots of great stuff going on in Guilt: director Alisa Palmer has injected smart movement sequences into the text, keeping the play from becoming too physically stagnant in its more narrative segments. As well, there’s an interesting, sandy set by designer Junge-Hye Kim, making literal the all-inclusive beach vacations of Flacks’ memories. Embedded in the sand are talismans of Flacks’ guilt, including airplane oxygen masks and a gelatinous brain, as well as a simple chair that provides Flacks with a small jungle gym as she excavates her adult life for sediments of guilt.

Ultimately, the play could likely be cut to an hour — there are occasional swathes of writing that dip into Freudian psychology and surface-level role-playing, and these segments left me yearning for Flacks’ more personal, accessible writing, rooted in her life as a Toronto mom. Much of the play is lovely and evocative (I’m thinking specifically of a moment in which Flacks recalls her son’s earliest days in the NICU).

As well, Flacks has an odd tendency to lean into TikTok humour — already-dated viral songs and dances make frequent appearances as she paints the complex picture of her guilt — and I found these sequences ultimately distracting, and more in the realm of non-sequitur than artistic choice. The kernel of Guilt is a strong enough solo show that these additions feel extraneous, without contributing much to the play’s dramaturgical thesis or aesthetic.

All in, I quite enjoyed Guilt, and I imagine the story Flacks has to tell will resonate with anyone who’s experienced divorce, as either a spouse or a child. With further honing, Flacks will have a gem of a solo show on her hands, but for now, that perfect iteration of the play lies just beneath the sand, ready to be dug out if afforded additional polishing.

Guilt runs at Tarragon Theatre until March 3. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments