REVIEW: Riot King’s Red examines Rothko’s uncompromising legacy

Those devout rectangles with their bleary edges which infuriated some and affected many — the colour field paintings of American abstract expressionist Mark Rothko have always communicated something preverbal.

Riot King’s production of Red, the volatile two-hander by John Logan, observes Rothko (Lindsay G. Merrithew) creating his Seagram Murals alongside a young, conflicted assistant and aspiring painter, Ken (Brendan Kinnon). Set in 1958 Manhattan and spanning two punishing years, the story of these elliptic murals — a singularly lucrative commission for the Seagram Building’s Four Seasons Restaurant — unfurls into an elegy for the artist.

Ken is hired to do the invisible labour of art production: stretching canvases, mixing paint, cleaning brushes, and applying ground colour (a base layer to each artwork which the play’s Rothko maintains is not a form of painting). The pair dispute with alternating ferocity, scrimmaging as if trying to better understand each other. Meanwhile Rothko depresses himself with the slow realization that he is compromising his art for commercial gain. Intimations of his eventual suicide are felt throughout, pockets of desperation peeking through the painter’s harsh exterior. “Be exact, be sensitive,” he pleads, or demands, of Ken at the outset.

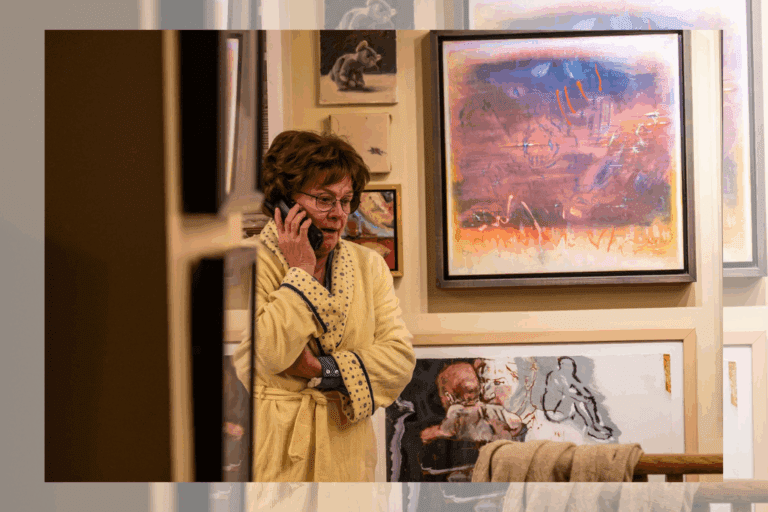

Director Kenzia Dalie reconfigures this history with finesse, wrangling the text’s agile tirades on modernism, dark anecdotes, and, naturally, the act of painting. The set design, also by Dalie, converts The Theatre Centre’s compact BMO Incubator into a homespun atelier. Splattered rags, loose wood, pigments, rusty cans, and a workstation lend the impression of orderly chaos — a “hermetically sealed submarine” of a studio, as Ken at one point describes it. The soft, flushed lighting by Kit Norman casts an abiding blush over the characters, a detail which calls to mind Rothko’s real-life claim that light is the instrument of unity.

The set’s aesthetic function is two-fold: the imposing oil paintings (deftly reproduced by abstract painter Ian Harper) and a record player for the artist’s diegetic soundtrack of Mozart and the like. The production design seems to unveil itself through these objects, which accentuate the text’s themes of procedure and resetting; bracketing each scene is a needle drop and the careful flipping of canvases to reveal more towering reds. They work symbiotically to insulate the space, with the grandeur of the paintings necessitating a booming soundtrack and the music stirring Rothko to paint.

In this production, questions of how to light a painting morph into questions of how to light a theatre, or faces, or bodies. Rothko, and by extension, the team behind Red, understand that our engagements with art will always be curated experiences; that these moments do not fully belong to us, but to the space in which they exist. In one scene, for instance, Ken turns on the fluorescent overhead lights to examine the paintings without their dim, romantic gloss, and the lights come up on the audience as well — a brief and uncomfortably sterile moment where the viewer is likened to the artwork, beholden to the same environmental whims.

Hence the artist’s climactic dilemma of exhibiting in a cafeteria for the uber-wealthy, even if under the guise of “ruin[ing] the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.” (In real life, Rothko would pull out of the commission and later donate many of the murals to the Tate Gallery in London. They arrived for exhibition the same day that he committed suicide.)

Keyed also into the criticisms of Rothko’s paintings — depthlessness, rigidity, interchangeability — this production of Red dispels such slander in its sheer motion: the ecstatic joy of covering a canvas with vermillion in under a minute, as primal as dancing or murder; or the exasperated slosh of paint mixing in the absence of speech. The actors move almost balletically across the stage, gesticulating, lifting, creating.

Merrithew’s portrayal of the artist is both stately and wounded, a fair approximation of Rothko’s disgruntled personality, as gleaned from his posthumously published writings. Kinnon’s Ken seems a slight departure from earlier productions which frame the character as bumbling or pathetic at the outset, living in the tall shadow of the murals and their maker. Here, the character is pluckier, still cautiously building toward his outbursts, but almost immediately onto Rothko’s contrived cruelty. (The actor also capably assembles large canvases before the audience, a feat in the small space.)

Merrithew and Kinnon’s dynamic plays like a craggy master against a tempestuous teen — by no means a slight at either character, rather, a transposition of one’s authority onto the other. The older one carps about the bohemian lifestyle of his contemporaries and the propagation of pop art (Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein catch more than a few strays), while the other stomps and sighs, only occasionally communicating the details of his devastating past.

Logan’s 2009 play arrived on the heels of the Great Recession, a moment wherein the tense intersection of art and commerce was sociopolitically prevalent. 16 years on, amid another threat of recession, the desire to make something uncompromising but worth protecting from corporate opinion feels especially salient. While Red cannot unseal the legacy of its paintings, this iteration conjures an immense compassion for the arts workers who try. As Rothko himself puts it in The Artist’s Reality, “the history of art is the history of men who, for the most part, have preferred hunger to compliance.”

Red runs at The Theatre Centre until April 6. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments