REVIEW: Theatre Rusticle’s Tempest goes gale-force in Act Two

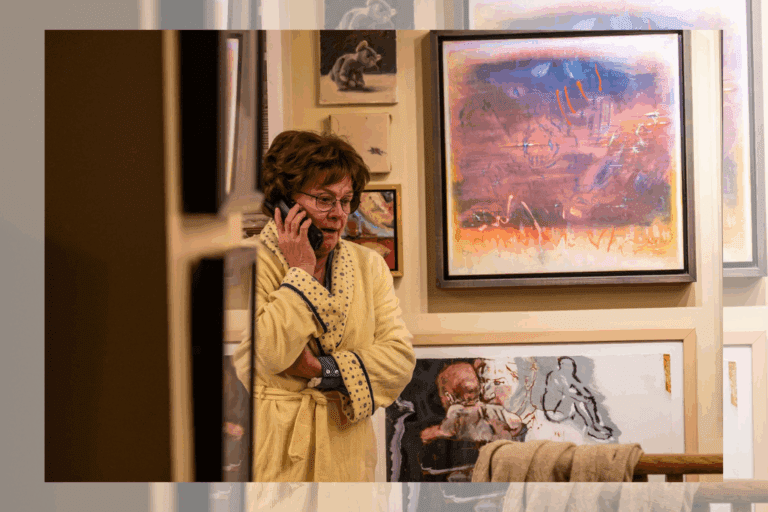

There’s something delightfully theatre school about Theatre Rusticle’s new production of The Tempest. Where else in Toronto but a scene study class is Shakespeare performed on an empty indoor stage (the Buddies in Bad Times Chamber, in this case), by a quintet of women in matching neutral garb, with the roles traded about essentially at random?

Furthermore, in the production’s conception, the well-loved indie physical theatre company, formed in 1998, mostly sidesteps the questions of intention often raised around the programming of classical texts (or, question: “why?”). That’s to say: director Allyson McMackon’s primary goal with The Tempest seems to be to do a show in Theatre Rusticle’s signature style (identified by its website as “spare yet image drenched”), with the choice of text coming off as almost secondary. When the production isn’t working, this un-intentionality produces an aura of aimlessness. But when it clicks, the show exudes a wild freedom, like a young person running drenched through a gale for the hell of it.

The production follows Shakespeare’s plot fairly closely. On an ocean island live Prospero (a sorcerer and the former Duke of Milan), his daughter Miranda, along with Ariel and Caliban, a couple of magic-infused servants. The titular storm wrecks a nearby ship carrying a court from Milan, including Prospero’s duplicitous brother Antonio, the new duke. Once the group is on the island, Prospero makes a series of moves aimed at clawing back his old title. Though the majority of his lines are retained (the production runs two hours and 45 minutes), the choice to have a five-woman cast may be an attempt to decentre Prospero from the narrative, as it parallels a throwaway line (here slightly emphasized through performance) regarding Miranda’s early childhood: “Had I not four or five women once that tended me?”

A pair of costume designers (Lindsay Anne Black and Brandon Kleiman) use accessories, including an abundance of gorgeous hats, to mark out the rotating roles with clarity. Despite this, the casting’s constantly shifting nature means the production is always one step ahead of the viewer. It’s at times confusing, and for me endearingly so; it goes a long way toward reproducing the overwhelming whirlwind of sensations that accompanied those first childhood dives into Shakespeare.

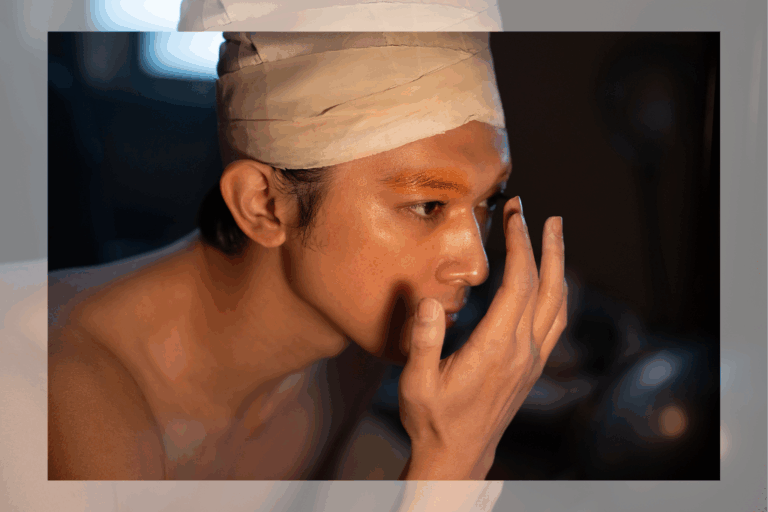

Rarely have I seen the Buddies space used to create such deep stage pictures. In a proscenium setup containing no scenography, the space is vast, and McMackon makes use of its full range, often placing the actors startlingly near or far. Then, in electric moments that put the “physical” in physical theatre, she has them push their bodies to the limit by running in circles about the space. Lighting designer Michelle Ramsay facilitates these explorations with the repeated use of a giant octagon of patterned light, which the performers traverse like an ethereal moonlit path or a sunny Olympic track as appropriate.

At other times, however, the production appears confined by the text. Particularly during the first act, the performers (Brefny Caribou, Jill Goranson, Beck Lloyd, Trinity Lloyd, and Annie Tuma) work hard at capital-C communicating the script’s meaning to the audience. This means plenty of hyper-literal gesturing, along with a frothy tone that at times made me wonder if the piece is intended for young audiences.

But the second act brings a richer texture, plus freer performances. The reason for the change? I’d chalk it up to the exposition being over. There’s less vital information for the audience to process, so performance is allowed to take precedence over text — and the show becomes disarmingly beautiful. Such late activations are common to English-language productions of King Lear, which often take until the storm to get exciting, but it’s curious to see this kind of arc in The Tempest; thanks to Prospero’s late-game speechifying, many productions actually slow down toward their end.

My first encounter with Theatre Rusticle, The Tempest at first frustrated me: why does the company appear to be leaning on what the show’s marketing calls its “inimitable style,” instead of working on thinking up new approaches? But as the production gradually unveils its splendours, the company’s impressive capacity for magic became clear. So here’s to further Rusticle revels, in all their schoolhouse playfulness.

The Tempest runs at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre until January 28. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments