At the 2025 Festival d’Avignon, politics were never far off

“It’s my first time,” the woman next to me confessed.

“It’s my first time, too.”

The Festival d’Avignon offers a booklet for virgin attendees, with a “bill of rights” for first-timers that includes:

- The right to imagine the piece was made just for you.

- The right to be bored or to fall asleep (without snoring).

- The right to leave before the end (even though sometimes you discover that you love the show at the very end).

I’d wanted to go to this festival in France for a long time. Since 1947, legendary directors like Peter Brook, Ariane Mnouchkine, and the late Robert Wilson have made a splash in this small medieval Provençal city where audiences gather during the summer for a month. Today, the festival features an international lineup more robust than any curated theatre festival in Toronto.

(To be fair, Avignon has had many decades to figure things out — still, it’s rare that a Toronto festival has both the budget and the vision to feature this many heavy-hitters alongside work by newcomers, while pursuing an overarching theme and being confident of selling out tickets, as Avignon did almost immediately after its box office opened this year.)

I’d performed and directed for festivals in Canada and elsewhere, but it wasn’t at all the same as being on the bum-in-seat side. There I was, in Avignon, rubbing shoulders with the umpteen visitors hungry for a good show. Before coming, I hadn’t realized that the festival is predominantly Francophone; English surtitles were sporadic. Luckily, my crummy French prevailed, because I came away feeling that here in Avignon, theatre mattered. A lot. In the stony fields of Toronto, that can be easy to forget.

Two festivals were running simultaneously — the 79th official one, plus Off Avignon, which has been going since 1966 and this year hosted 1,700 shows from 30 countries. I couldn’t bite into a croissant without some actor handing me a card advertising their show. I already had tickets to nine main-festival productions, and managed to squeeze in one Off show, which I chose because the actor sold it to me with such passion. It was a hard choice, given that the streets were plastered with posters for anything from Shakespeare to Scorched by Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad.

Speaking of Mouawad, in 2009 he staged a trilogy of plays at the prestigious Cour d’Honneur at the Palais des Papes, a massive outdoor venue. This year, I joined around 1,999 other audience members there for my first show at Avignon, the opening night of the entire festival: NÔT, a dance-theatre piece based on the tales of Scheherazade, created by the Cape Verde-born, Lisbon-based Marlene Monteiro Freitas. Twenty minutes in, many people put that bill of rights in action and streamed out of the theatre, though, shockingly, some stayed to boo.

I admit that I left early, too — the grotesque vignettes scattered across the massive stage exhausted my patience. The mostly male-presenting performers wore girly clown-masks while performing the drudgery of housework, including windexing their “vaginas” and stripping the sheets off bloodstained beds. As one of them walked out into the giant audience miming vomiting into a potty and then eating his vomit, boredom set in. The show promised to be about a woman’s resilience; in Freitas’ production, Scherezade survives by arousing disgust.

I wondered if I’d come in a bad year. The 2025 program foregrounded dance, and having seen so many great Canadian and Quebecois companies, from La La Human Steps to Kidd Pivot, I was feeling a little snobbish. Yet the very next day, I joined an ecstatic standing ovation for When I Saw the Sea, a fusion of storytelling and movement with a superb live score, directed and choreographed by Lebanese director Ali Chahrour.

Speaking in Arabic and Amharic, three women struggle to escape the kefala system in Lebanon, which subjects migrant domestic workers to a kind of modern slavery. Amid explosions and phone calls and blinding light, Rania Jamal tells her story of being a child of rape. Next, Zena Mussa mentions that she has to finish her cleaning job in order to get to rehearsals. Suddenly you realize that these women are performing their own stories, that Charour has turned non-professional activists into accomplished artists. The image of a silk blanket fluttering down on a nameless dead girl lying on a warzone road will stay with me for a long time. “I cry, and the world cries with me,” sings musician Lynn Adib.

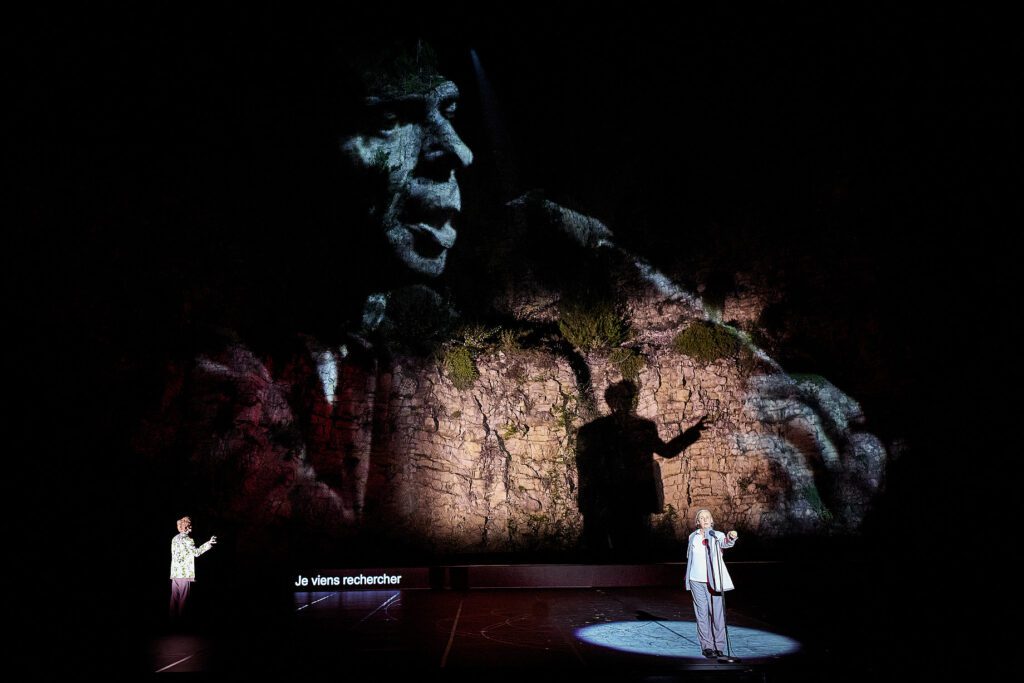

Another highlight was Brel, a tribute to the legendary Belgian singer. I sent a mental congratulations to Why Not Theatre’s newly Dora Award-spangled adaptation of the Mahabharata as my bus climbed the hill to the quarry where Brook staged his version of the same material in 1985. Brook’s show was nine hours long and ended at sunrise: luckily, Brel was not quite that ambitious.

A thousand people gathered outdoors, waiting for nightfall, gazing across a rectangular black floor toward the backdrop of sheer rock. If Michel François’ scenic design is minimal, so is the cast, both wearing gray suits (designed by Aouatif Boulaich): the Flemish grande dame of dance, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, age 65, and her protegé, Solal Mariotte, age 24. Moments into the show, a third performer appears — Jacques Brel himself, projected on the rock. Though the youngster dazzles with his break dancing, his elder steals the show when she strips naked in the dark and Brel’s face is projected on her body as he sings the saddest song in the world, “Ne me quitte pas.”

The festival featured so many non-narrative collages that I began to find straight-up narrative text downright bold, whether it was an Off show about Hemingway, or an updated version of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, stunningly directed by German stalwart Thomas Ostermeier. It was Ostermeier’s seventh show at the Festival, and his eighth-ever Ibsen. At a discussion led by the festival, he described the play as a body blow, a treatise on the precarity of a family that gets destroyed by the self-righteous ideals of the bourgeoisie. Richard Rose recreated Ostermeier’s version of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People at the Tarragon in 2014; maybe The Wild Duck will take the same path. I sure hope so.

Set in the present, Ostermeier’s production unfurls on a revolving stage, moving from the claustrophobia of comfort to the mess of a cramped apartment. A mother and daughter enable a narcissistic father until the mother’s secrets are revealed with disastrous consequences. A major high point is actor Stefan Stern, playing the father, who makes a meal of playing heavy metal in his underwear. His explosion at the climactic point of the play is one of the most shocking minutes I’ve spent in a theatre.

The festival aims to be as accessible as possible, a goal reflected in reasonable ticket prices and free activities such as a daily gathering where directors like Ostermeier talk about their work. Its website is adapted to the needs of people with visual, motor, or cognitive disabilities, and there’s a dedicated team to support people with reduced mobility. Certain venues have hearing loops, and many performances are accessible for the blind or the visually impaired.

Under Tiago Rodrigues’ leadership since 2022, the festival highlights a different language every year, and in 2025 it was Arabic. Given the situation in the Middle East, I wondered whether this choice explained the high level of security. Police with machine guns sauntered amongst the throngs of theatre-goers, and at the door of many shows, our bags were searched, with security making us drink from our water bottles to prove they weren’t combustible.

In all the productions that I saw, politics were never far, mostly cries of anger against right-wing extremists and protests against the genocide in Gaza. After I left the festival, Swiss director Milo Rau presented a tribute to Gisèle Pelicot, whose rape case has galvanized the fight against patriarchy. Called The Pelicot Trial, it was a night of readings based on documents and commentaries, presented by actors, lawyers, activists, and scholars. Rau is the director of the Vienna Festival and launched his Resistance Now Together movement at a morning talk at Avignon, warning that attacks on culture are the hallmark of populist regimes. This warning was repeated by the artists and leaders of cultural institutions that he’d gathered from Central Europe to France, Greece, and Egypt.

That very night I watched a high-energy ensemble of dancers sing “How can I resist / I want to resist,” in Mette Ingvartsen’s frenetic Delirious Night. Who doesn’t get that sentiment these days – not to mention the following verse, perhaps my favourite lines of the entire week in Avignon: “I’m so sick of payin’ the rent / I wanna fuckin’ die every time I pay it.”

The 2025 Festival d’Avignon ran from July 5 to 26. More information is available here.

Always a treat to read your writing, thinking and art-foraging!