Bluit Nanche: How My Friend Took Over a Multimedia Art Installation on a Dare

At 11 p.m. on October 1, I filled up my flask, put pants on, got out of bed (in that order), and biked to the big, inflatable, smoke-squirting sun. As I waited for my friends, I mentioned to a stranger in the audience that the actual sun would be rising quite shortly, and so I didn’t understand what the fuss what about, and she looked at me absolutely befuddled as to why I existed.

For those who are confused: Nuit Blanche is a free, annual, citywide celebration of contemporary art, from sunset to sunrise. These festivals began in France in the late 1980s and have since spread to cities across Europe and Canada. But don’t worry, despite those rigorously historical sentences I just Wikipedia-d, I’m not going to try and tackle the socioeconomics of Nuit Blanche’s mass commercialism, because 1) I am done researching for the day, and 2) … You know what? I don’t need a second reason.

For the purposes of this article, I will also hereby refer to Nuit Blanche as Bluit Nanche, because A) it’s fun to say, and B) see reason 2 above.

When my friends Darcy and Grace arrived at the inflatable sun, they’d been drankin’ and Bluit Nanche-ing for a couple of hours, and it was time for me to catch up. Grace also shared her new strategy for skipping the long lines: cut in front and simply pay the social consequences. We biked up Spadina and right off the bat (outside a high-end record and kitsch shop hosting the art installation: piece of construction paper with lasers on it), I overheard a woman say to her friend, “At a certain point, everything’s art.”

Turns out this statement really does sum up the festival.

Since 2006, Bluit Nanche Toronto has hosted nearly 1300 art installations. Here are five from this year’s selection:

- A video installation where, after you listen to the sound of a fly for a few minutes, you watch a glass box float through a desert.

- An upright piano turned upside down, its eighty-eight keys scattered below—though, thankfully, still producing atonal horn music.

- A four-hundred metre strip of books strewn across the pavement.

- Three feet of a Kensington Market alleyway decorated with cardboard cylinders and Christmas lights (accompanied by the white, hipster-bearded artist himself, talking about how his piece addressed homelessness).

- A female mannequin on a Segway, decked out with bracelets, lipstick, a fascinator, rolling steadily forward on a bedazzled treadmill.

And what’s exciting is: I completely made up two of those things.

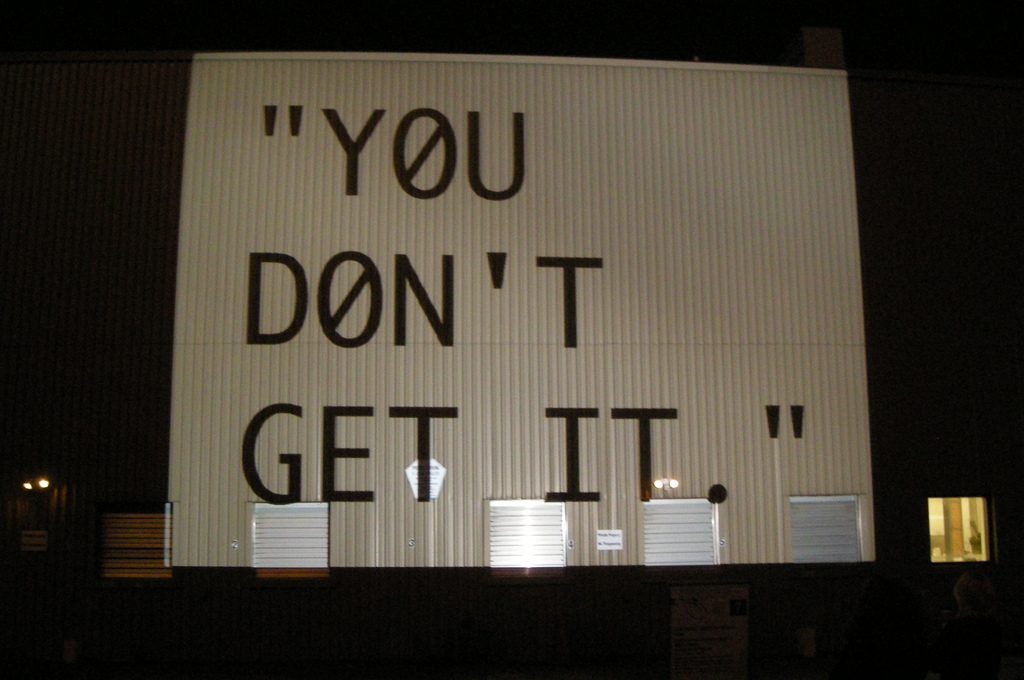

After biking around for a couple hours feeling either too smart or not smart enough for the art we were seeing, we stopped near Richmond Street at a big multimedia installation shipped in from the Netherlands. The piece was entitled Waiting.

We walked into a long, echoing lobby, and there was a stand with two TV screens playing two different angles of the same black-and-white scene: a woman waiting in a restaurant. We walked further and there were two more screens, with the exact same endless video. Another twenty feet, another set of screens, woman still waiting… Then we arrived at the “climax”: two huge screens (you can guess the video) and below them, surrounded by tables and chairs, a man playing the most aggressively boring piece of music on a slick grand piano.

Waiting. Photo by Erwin Olaf, courtesy of Nuit Blanche

As I was doing “research” for this article, I looked up Waiting on the Bluit Nanche website, and I was nervous that the description of the piece would prove that I had missed something… No, not at all. It was a piece about a woman, waiting, and we, the audience, were to experience her waiting, while also waiting ourselves for something, anything, to happen.

But then something did. Grace turned to Darcy with nothing but mischief in her eyes and said, “Darcy, I dare you to go over there and start dancing.”

Darcy Gerhart is an actor known for her fine work at the Shaw Festival (and Ravi Jain’s play at the Theatre Centre with the super long title), but she also happens to be a trained ballet dancer. Maybe it was the drankin’, but probably it was just one of those rare moments where courage and impulse coexist: Darcy zipped off her turquoise biking jacket (leaving her in a long-sleeve black top and black leggings), walked to an open area next to the man playing offensively little piano, and began to dance.

Heads started turning, a new crowd gathered, and Grace got out her phone, turned to me, and said, “I love her.”

For twenty-five minutes, Darcy danced, and nobody, no audience member at least, thought it was anything less than planned. People stopped chatting and meandering. They formed a crowd, at first only ten or twenty people but soon fifty or sixty. Darcy ran and suspended, whipped her blonde hair, and perspired through her clothing; she rolled on the floor and hovered high on her toes, and for a brief period, this trite, obnoxious instillation piece had urgency and meaning. The audience who’d come to the installation was hit over the head with non-action, with two-dimensional loneliness, but right at the end of this intentionally stagnant presentation there was a real human, sweating and bold, reacting spontaneously to the now-purposed music, her own impulses, and the weight of her audience’s collective gaze.

At one point, an event coordinator walked up to the security guard, who then came up to me.

“Is that girl your friend?”

“… Not really, I just met her a few minutes ago, and she asked me to watch her bag.”

“So she’s not your friend?”

“No.”

Too smart to interrupt the performance himself, he went back to his post, shrugging at the coordinator.

A few minutes later Darcy stopped, breathed heavily for a few seconds, then walked away. Grabbing her stuff, Grace and I followed her past the security guard and out the revolving doors.

At a certain point, everything’s art.

The night was colder now, and as we unlocked our bikes and started to walk, we felt an internal struggle between our late-night high and fatigue. The adult version of a sugar rush coming down.

We went around the corner into a large, Bluit Nanche–filled building. Inside, a coffee bar still making espressos at 1 a.m. was also selling water in small jars with tiny, maple-syrup-bottle handles for seven dollars each. Grace cut in front of a long line, only to emerge sixty seconds later to report that a woman with a guitar was jamming to video projections. “… It’s like Cheerios. Everyone can digest it, it’s kind of good,” she said. Down a side hallway I miraculously found a lineless bathroom. It was empty except for one very disheveled-looking man, standing at one of the two urinals. I stepped up to the other, and he turned his head to me.

“Where the fuck even am I right now, bro?”

“I hear yah, man.”

Then he looked slowly downward and sighed: “Ugh… Can’t even piss.”

We’re all west enders, and as we biked through Trinity Bellwoods Park, we saw the other people who were done seeing art but didn’t want to go home, spread over picnic tables and benches. We overheard a house party at the edge of the park, whoops and laughing and rap music. We hit the brakes, locked our bikes one last time, strode through the open back door, and spent the next ninety minutes dancing with strangers in a crowded kitchen, until that also faded, and we slipped out and parted ways to go home.

I don’t know if I’m a good Bluit Nancher. I struggle with visual abstraction, and I can never really shut off that snarky part of my brain that would rather formulate jokes than do the work of letting art actually penetrate. I’d rather drink, cheer on my friend, dance, and sweat. But Waiting created the space for Grace’s provocation and Darcy’s performance, for a meeting of installation and spontaneity, and that confluence shifted something. I learned that there’s room for me in these Bluit Nanches, these sleepless nights. There’s room for all of us.

See you next year.

**Be sure to check out history, photos, and submission information at Bluit Nanche’s website, www.bluitnanche.ca.

Comments