Carving Out a Career

Let’s paint a picture of what’s happening right now. Erum Khan and Micaela “Mick” Robertson, who started working on the original version of Concord Floral as teenagers, are now in their early 20s. At the time of this conversation, Erum and Mick are getting ready to put on a new staging of the show. They’re sitting backstage in the greenroom of the Bluma Appel Theatre at Canadian Stage, a few hours before their fourth preview performance. Cast members trickle in and out as they get prepped for the show. Some rush through their homework, a few prepare their dinner, and the rest chat and catch each other up on their day so far.

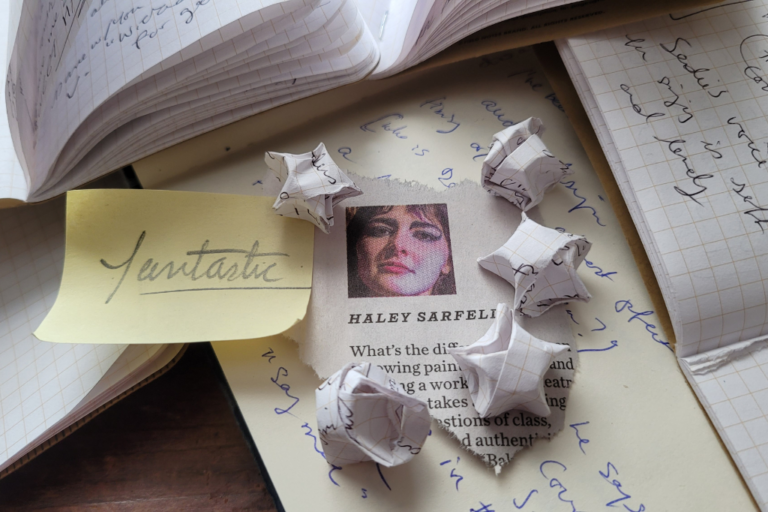

Erum (left) and Mick (right).

ERUM

It’s weird to be sitting here right now like this. I’m having a flashback to the conversation we had in mid-August at the cottage during our first rehearsal weekend. That was our first freak out at having basically switched roles. You went from being assistant stage manager for the 2014 iteration of Concord Floral to current performer, while I transitioned from performer to assistant director.

MICK

Yeah, and that was such a funny moment too, because it was right after our first table read of the play, which was an unexpectedly undressing experience for myself. And we both approached each other in our pajamas, vulnerable, like big babies—

ERUM

Yes, we were going for a real professional vibe.

MICK

Very serious professionals. And it was just so funny, because everyone else was in the other room, and we both just looked at each other and immediately knew what the other was thinking. And to be fair, we weren’t really freaking out, but it was clear we were both feeling pretty uncomfortable at the sudden shift.

ERUM

I wouldn’t say we were super emotional or anything but we had a very matter-of-fact conversation about how weird it felt to be in such different roles than what we were used to, specifically for this play. I mean, I only knew this piece through performance and I always felt attached to it as a member of the cast. Concord Floral is also the first theatre production I’ve ever worked on, and it’s been the main source of my upbringing as an artist. I’ve been involved with it’s creation process since I was seventeen years old (I’m twenty-two now), so it’s been vital in influencing the ways I approach art and the work I’m interested in.

And then to be sitting there and hearing the play being read aloud by different voices and knowing I wasn’t going to have a chance at performing in it again—it kind of struck me that that part of my identity and relationship to the piece was over. Which also meant being part of the cast and the specific relationship with fellow performers was now going to be so different, since I was part of the directing team. Which was quite heartbreaking. Whereas for you I’m sure it was the opposite.

Photo by Erin Brubacher

MICK

I think I realized that just because I had grown to know the play so well over the years, that didn’t mean I would instinctively have a grasp on how to perform it, which is frustrating—especially when I take into account that I’ve directed other actors in these roles. It was such a strange feeling. Being part of all these different roles exposes you to a range of vulnerabilities that aren’t apparent until you’re performing the new position. I felt oddly drained after the first reading and my feelings towards the play suddenly felt muddled and less clear than they had before, because I was looking at it from an entirely new perspective. Of course this drastically changed over the rehearsal process, because these feelings are normal, and eventually we come to terms with those changes.

ERUM

I remember this feeling of being in a position that was obviously so different from before and yet completely familiar as well. A lot of that had to do with the way our co-directors, Erin Brubacher and Cara Spooner, have created an environment where having ongoing discussions around our thoughts and interpretations of the play act as vital guiding principles in shaping the kind of work we do. So shifting roles also felt quite natural and organic alongside them. It’s this weird mix of knowing a piece so well from a very specific perspective and then suddenly “being on the other side” and having to work and understand it in an entirely new way. I mean, this was also the first time I was even able to watch the play, because as a performer I had never seen it. And suddenly I saw things that I never noticed because I was observing it from a directorial viewpoint and adjusting how I engaged with it through this new lens.

MICK

I also think, especially for the two of us, engaging in multidisciplinary roles is something we are actively interested in pursuing and so, in a way, we’re more willing to take on various positions.

ERUM

Definitely.

MICK

It’s kind of fascinating and really allows us to grow as artists rather than just being like, “Okay I’m an actor and that’s all I will pursue and perfect for the rest of my working life.”

… In a sense there’s something I will miss by not doing that, not being a single-disciplined artist. The romance of a monogamous relationship with one role is compromised. Having the ability to master one craft to perfection is a notion that I think multidisciplinary artists forfeit. But at the same time, each of your roles influences your work in another. As a mentor once told me, “You can only write one play about being a playwright.” Range of personal experience helps to create more interesting pieces, so even within my theatre life I’ll aim to get as much range and experience as possible. Maybe there’s a healthy balance between the two…

ERUM

Yeah, I also find that by transitioning from one role to another in the theatre world, you really get to understand another aspect of a role you aren’t in at the present moment, you know what I mean? For instance, a few years ago I went from performing to playwriting for the first time and suddenly I was able to gain a better insight into what it means to be a performer while I was writing. As I developed text and dialogue, I became more attuned to the people and spaces around me. It allowed me to better grasp how a piece of text may be structured and the kinds of questions you should ask yourself when trying to understand a script. It’s this interesting dynamic where no matter what you’re doing, you’re constantly contributing knowledge to all these various disciplines you are part of.

MICK

I think it’s also nice to just have all these outlets always available for you. On a very practical note, having a larger skill set opens you up to more opportunities for work. It can be a little intimidating, how busy and demanding this lifestyle seems to be. Like, I’m surrounded by many multidisciplinary artists and they’re always involved with numerous projects at once, which can obviously be quite exhausting but also pretty exciting at the same time. It seems to be the norm. As theatre practitioners, we’re very rarely committed to just one project. Ideally, you want to be set up so that as soon as you’re done one project you’re able to transition into another job. Not everyone is fortunate to constantly have work available to them, and I’m hoping that being multidisciplinary will offer me more opportunities.

ERUM

I wonder how much that affects the process of creation then. If people are always in a frame of mind where they’re simultaneously involved with other work, are they able to fully commit to a piece of work without being distracted by thoughts of another project? Or do these projects just influence and improve on one another?

MICK

Is the notion of perfection compromised? Umm… not always, I don’t think. But even if it is, is that a bad thing? Some of my favourite works have by no means been technically perfect. Concord Floral’s acting is charmingly rough around the edges. It’s intrinsic to the piece.

In terms of projects influencing each other, I think they absolutely do benefit one another. My assistant stage managing taught me to write. I used the job as a learning experience. It allowed me to sit at a table with people who are much smarter than me and observe how they work. That experience taught me how to build and maintain narrative logic and story structure. I’m planning on always sneakily using my current position to benefit my work in another.

Erum Khan’s show Becoming is on at the Rhubarb Festival from February 16 – 17 and a staged reading of her play Noor will take place on February 23. For tickets or more information, click here.

Comments