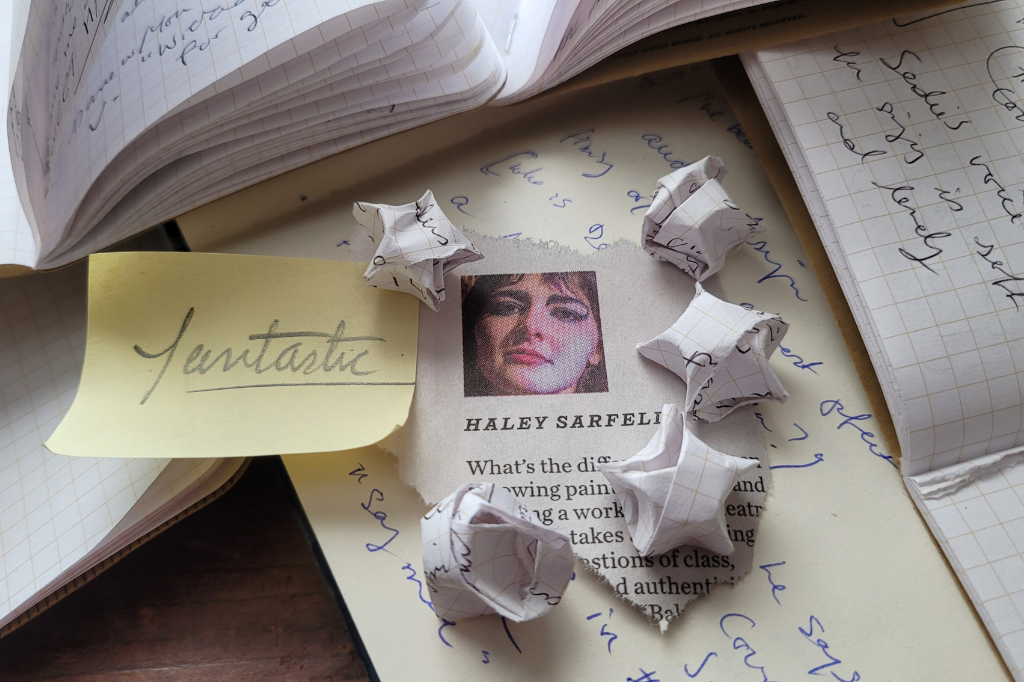

Every play is fantastic: A small-city theatre critic’s manifesto

I will never see a bad play.

I will never get bored. Every production will be excellent. Inspired. Fantastic. Garbled lines? No, that’s how it was written in the script. Missed cues? …sorry, was that supposed to be me? My bad. Wait, no, not bad. Never bad. Fantastic.

My top priority as a critic will be to furnish every marketing team with as many easily quotable compliments as possible. I’ll do this dutifully and without ambivalence. No artistic director of a professional theatre company will ever feel compelled to text me before breakfast on a Saturday morning, “so, you really hated the show, eh? Not one useable quote,” or follow up – maybe after a gulp of coffee – with, “OK, we found some.”

I won’t get the jitters. I’ll have no anxiety. I’ll never mute my phone outside the theatre. I will never wonder about the word “professional.”

I will never, ever, ever stray from the press release. I’ll spend hours each week re-arranging boilerplate text into polite blear so I can avoid wasting energy on original thought. In fact, I’ll save time by writing my review before I see the show. I might not bother showing up at all. It’s great! Go see it! You’ll love it! So will I!

I’ll never sit next to an audience member who’s picking their nose and find it more interesting than the action onstage. I’ll wear a mask for health reasons, not because my face has anything to hide. When my next paycheque comes through, I’ll invest in some hair elastics so I can pull my bangs back and let everyone get a good look at me. Turn up the house lights, please! Someday, I’ll dip into my millions of small-city theatre critic dollars and treat myself to Botox, too, just to ensure that my eyebrows can’t move a millimetre, lest my face be misconstrued as having a less-than-congenial expression. A needle in the forehead can’t be more painful than a three-hour musical, right? Just kidding. Art is painless. Fantastic.

Somebody help me out here. Do you want a reviewer, or do you want a marketing person? You can hire me as a marketing person, you know. That’s a job I can do. I have a whole portfolio for that and I charge market rates. But – and I’m just thinking out loud – maybe don’t invite me as a critic if you don’t want a critic at your show.

I do prefer being a critic, though. I’ve been a critic for many years. In fact, my first two reviews were published in 2006. The objects of my analysis were classic works of literature: Nancy McArthur’s The Plant That Ate Dirty Socks and Mary Pope Osborne’s Magic Tree House: Dinosaurs Before Dark.

I was in grade four, I had a gig with the school newsletter, and I was living the dream.

After achieving such lofty journalistic success, I decided to lay low for a while and develop my craft. At the age of nine, I zipped up my pencil case and took a sabbatical from public life as a critic – though I made sure, especially in my teen years, to uphold a robust practice of criticism in my private life.

Seventeen years later, I returned to the glamorous profession of public criticism, trading my well-loved chapter books for tickets to local theatre productions. Since then, I’ve been writing weekly articles for a theatre blog in Kingston. Last summer, I popped over to Toronto to participate in the New Young Reviewers program with the Toronto Fringe. This winter, a local newspaper hired me as their resident theatre critic.

My local scene’s tight-knittedness can feel like a homemade sweater – a thoughtful gift, sure, but a scratchy one, and often clingy in the wrong places.

While I enjoy the job, it’s not without complications. Theatre is full of, well, drama. My local scene’s tight-knittedness can feel like a homemade sweater – a thoughtful gift, sure, but a scratchy one, and often clingy in the wrong places. As an artist myself, I usually have some level of social connection to the people whose shows I’m reviewing. This can pose problems, especially if we’re operating under the assumption that a critic is supposed to be critical – which means discussing a piece’s faults as well as its merits. Balancing honesty, gentleness, humour, and integrity can be tricky. Even when I don’t know anyone involved, someone always knows my boss or my boss’ boss, and inevitably there are times when grumpy comments, angry emails, and cold shoulders emerge.

I try to take it in stride, but lately, I’ve decided that enough is enough. My role has become far too unpleasant. I can’t expect other people to change, so if I want to survive, I need to change my outlook as a critic. That’s why I’ve developed this manifesto for my work moving forward. You can use it, too, if you’d like.

Let’s proceed.

I’ll never have a headache. I’ll sleep well. I’ll have no biases and no self-doubt. Nobody powerful will ever give me the creeps or say anything weird. No member of a production team will ever send me a deluge of uninvited texts or overshare about problems behind the scenes. I’ll never get tired or annoyed. My reviews won’t scream when you snip them out of context and spell my name wrong in the attribution. You did your best! Good for you!

My jokes will always be taken in good faith. I’ll never argue with an editor. I’ll never have my voice squeezed out of my writing like toothpaste in the hands of a toddler. I’ll never see a local theatre blogger receive hateful comments for a fairly mild review, so I’ll be fearless and unfettered in my opinions. I’ll never piss anyone off. I’ll have no empathy and no courage, because I won’t need it – everything is always fantastic!

I’ll never tell a friend a play was good and then feel embarrassed when they hate it. I’ll never temper my expectations based on an ensemble’s budget or level of experience. I’ll never worry that giving too much flattery to okay-ish shows will turn me into the boy who cried wolf once a truly good play comes howling for my heart. I’ll never choose tact over truth. I’ll never choose truth over tact. Truth and tact are best friends and they’ve been kissing sloppily for 90 minutes and it’s an avant-garde performance art piece I wrote and produced and directed and it’s fantastic! You’ll love it! Please review it (unless you have anything critical to say)!

Once I file my review, public opinion will be set in stone forever. In under 800 words, I’ll have done the thinking for all of us. I’ll take my opinions very seriously, and so will you.

“Facetious” isn’t in my vocabulary, and even if it were, I wouldn’t use it. I don’t want to challenge anyone or get in the way of their stagnation. I’ll never change my mind or anyone else’s. I only have easy ideas, and I only use words that everyone’s heard of. Easy words, because my job is easy.

So, from now on, a play is never boring, it’s subtle. It’s never overwhelming, it’s lively. It’s never unconvincing, stiff, dated, offensive, schlocky, repetitive, so-so. It’s good, good, good, good, good, good, good! I love it! You’ll love it!

Fantastic!

Comments