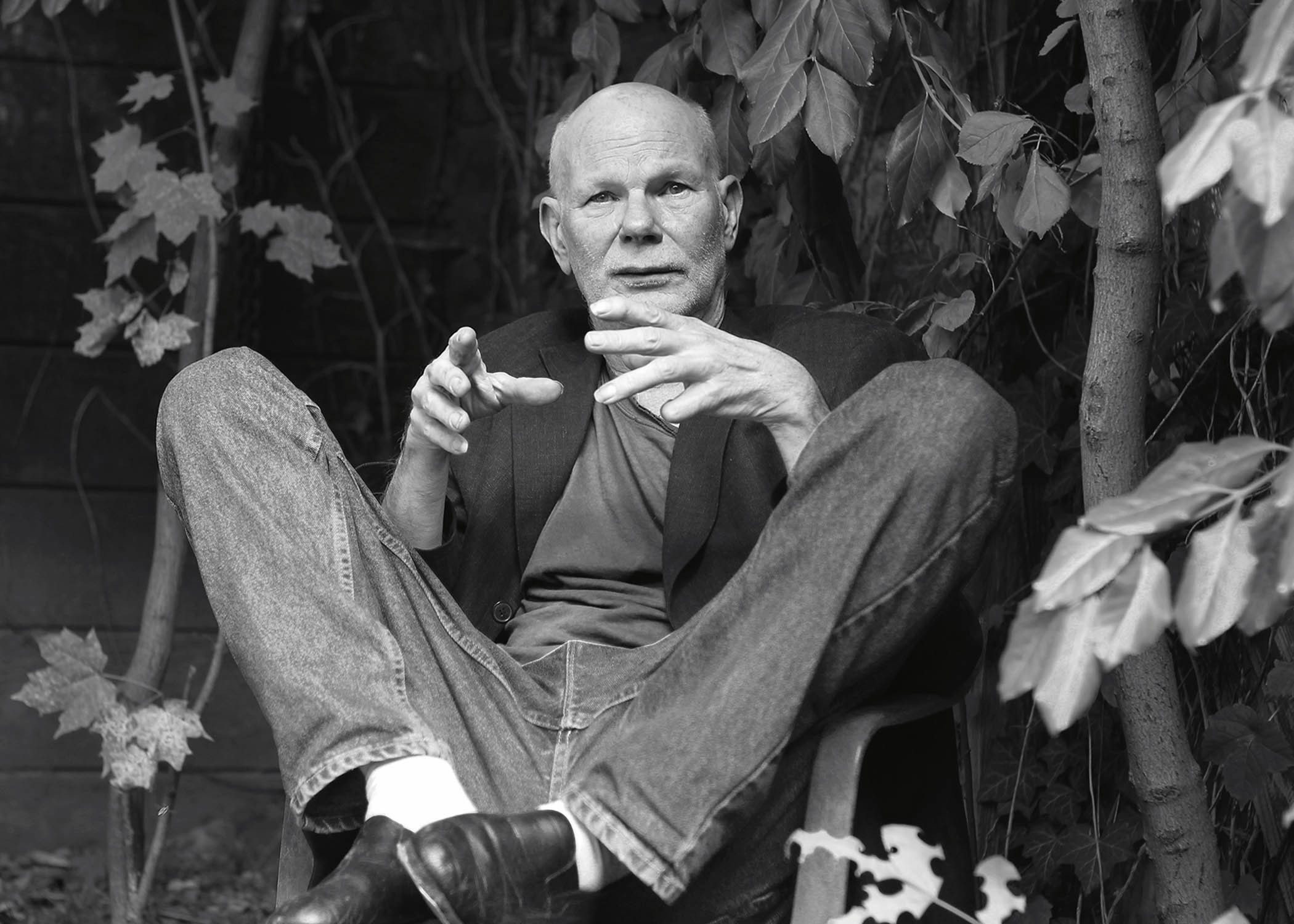

Director Hillar Liitoja was ‘pathologically uncompromising’ in his pursuit of great art

If you’re under the age of 45, there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of Hillar Liitoja.

Although the influential Canadian theatre director’s career spanned four decades, he produced his best-known works in the 1980s and 1990s. By the early 2000s, when I first met him, his output had declined, a result of funding cuts to his company DNA Theatre and a general frustration with the systems of government-subsidized art making in Canada.

When he died on June 2, 2023, two weeks shy of his 69th birthday, no one close to him seemed very surprised. After suffering a stroke in 2022, he finally succumbed to a blood infection, the result of a pressure ulcer he developed after refusing to get out of bed for weeks. It’s almost painfully poetic that Hillar died because he essentially refused to move. Famously dynamic during both rehearsals and performances, his enthusiasm for art often engendered motion. This included his habit of “conducting,” enthusiastically waving his hands while watching shows as if he were leading an orchestra.

An avid pianist from the age of six, he completed a BFA in music performance at the University of Toronto before ultimately quitting the instrument and turning his attention to the theatre. His career for the stage began with Pound For Pound (1982), the first in a series of shows exploring the poetry of Ezra Pound. His big splash came with This Is What Happens In Orangeville (1987), a controversial work based on the true story of a 14-year-old murderer, later remounted at Montreal’s Festival TransAmériques. He followed this with his infamous eight-hour Hamlet (1989), in which Ophelia, played by a teenage Kirsten Johnson, smeared her body with vegetables during her descent into madness. 2002’s The Observation (his last major work before DNA’s funding began to disappear) invited one audience member at a time to walk through his home, each room having been transformed into a dreamscape, including a front parlour filled with live birds.

In his later years, he became interested in dance and began working with performers from the National Ballet of Canada (NBC). He staged a handful of experimental shows with NBC company members, including I Of The Beholder (2006) and Red Light Green Light (2014). Then, as DNA’s funding dried up, he turned to writing and podcasting, but he never seemed to find the same charge in other mediums that he did in performance.

Though his shows sometimes addressed similar themes, he didn’t have a singular style. One piece might have 45 performers and span multiple locations; another would feature a single actor and a handful of spectators. Many works functioned as a kind of structured chaos, and involved a series of interacting scores that allowed elements to meld in different ways each night.

He had no problem breaking the conventional dictates of theatre, particularly when it came to safety. Exit signs were frequently covered to create complete blackouts and pieces sometimes featured live fire or animals. A DNA show, both in rehearsal and in performance, was never a “safe space.” It wasn’t an environment where you were supposed to feel comfortable. Instead, his creations brought together all the joy and terror and beauty and chaos of being alive. You never knew exactly what you were getting into with a DNA show, but you knew you wouldn’t be bored.

Hillar was pathologically uncompromising and pushed his collaborators to their absolute limit. Some couldn’t hack it. Others returned again and again, driven by a curiosity of what might be next. He loved working with young people and many of his collaborators did their first DNA shows as teenagers. These relationships were reciprocal; he mentored them in his methods of creation and thrived on their energy and fearlessness. His magnetism connected a community of performance eccentrics who collaborated and partied and fucked and occasionally married each other.

Throughout his career, he struggled with the disconnect between funding systems and the nature of creativity. He believed artists should have whatever time they need to bring projects to fruition and refused to show works before he was completely satisfied, a challenge when arts councils insist that presentations adhere to an agreed-upon schedule. He also struggled within the community. While many loved working with him, his eccentricities led him to burn bridges, meaning he lost out on certain opportunities.

He was just as exacting in life as he was in art-making. He kept copious notebooks, always insisting on specific types of pens and paper. (More than once, an assistant was sent to the store mid-rehearsal to exchange incorrect writing implements.) He would jot down everything he wanted to say before a phone call and refused to return voicemails if callers didn’t repeat their number twice, as requested on his outgoing message.

His personality was full of contradictions: generous and stingy, loving and cruel, wildly funny and deadly serious, passionate and dejected, chaotic and meticulous, child-like and infinitely wise. He was famously impatient, but could spend hours poring over the same few lines of poetry or replaying 10 seconds of a baseball game. He looked to the world as a perpetual source of awe and magnificence and was always truly himself. He was also a director who couldn’t exist today. His approach would get him cancelled almost immediately — ironic, given that so much of his work, and that of his generation, sought to create possibilities for those who came after.

I never worked with Hillar, but I was highly influenced by him without entirely knowing it. When I first graduated from theatre school, most of the artists I initially collaborated with (many of whom I interviewed for this piece) had passed through his company. We were never really friends, per se, though he frequently came to shows I was doing and I went to many of the infamous parties held at his Bathurst Street residence.

I’ve spent the last few months pondering what meaning can be taken from Hillar’s death and what this loss represents for our community. Through the haze of emotion, three things stand out. The first is the need for greater attention to the preservation of performance history, a difficult task with works that don’t lend themselves to publication in traditional script form. The second is to have greater compassion for our industry trailblazers and a recognition that the combative tactics younger folks might find abrasive were often critical in building our sector. The third is to understand that genius can be messy and artists are rarely perfect people.

The best art is dirty and scary at the same time as it’s brilliant and beautiful. We need to leave space for artists to be all of those things too.

Thanks to the many people who shared their memories for this article: Allison Cummings, Bob Wallace, Cathy Gordon, Chad Dembski, Ingvar Liitoja, Kevin Rees, Kirsten Johnson, Magdalena Vaskó, Steve Lucas, Sky Gilbert, and Wendy White.

Comments