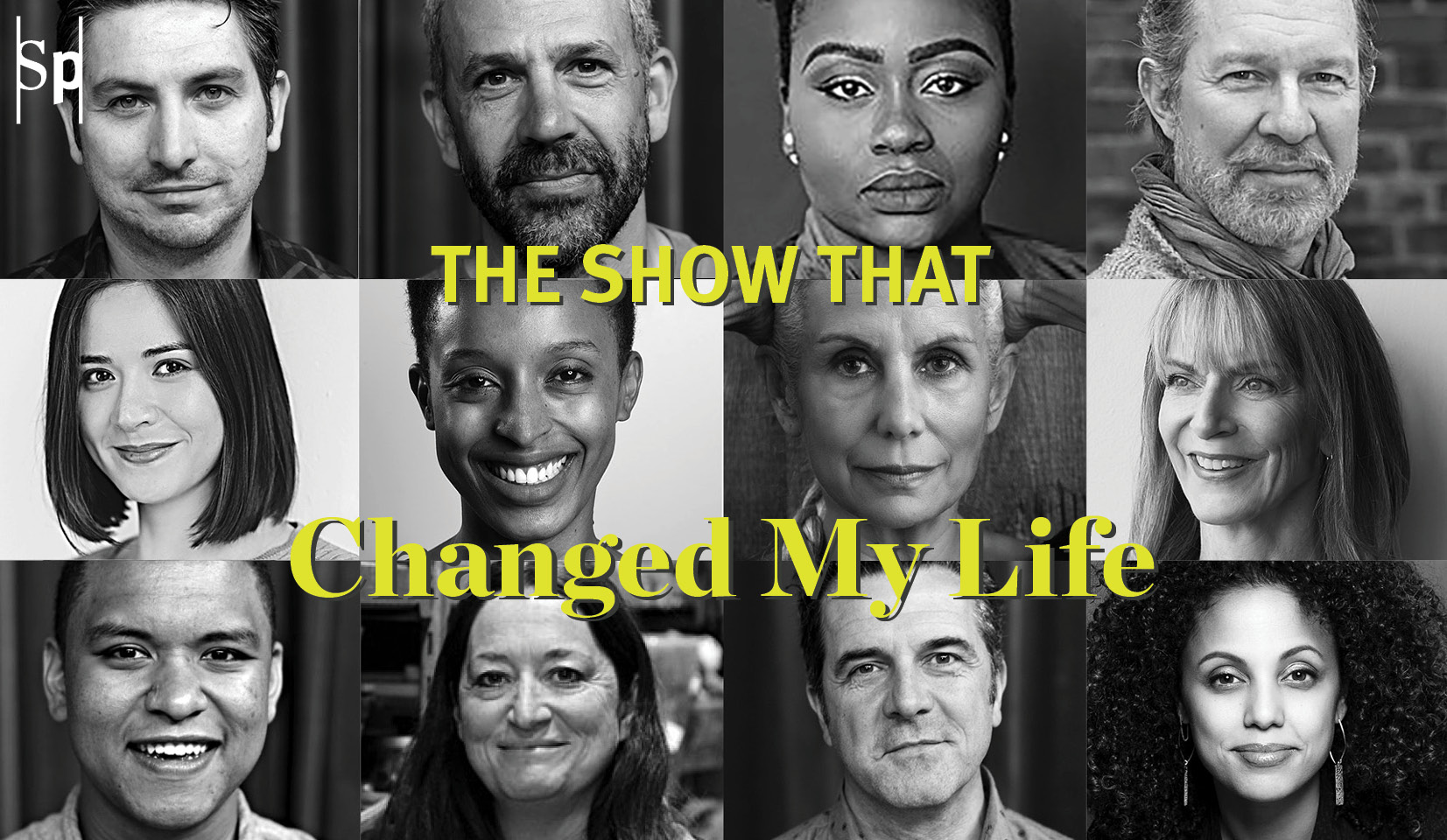

How ‘The Show That Changed My Life’ Revived My Optimism

I haven’t set foot in a theatre since February 2020.

A full year into pandemic lockdowns, I’ve seen Zoom plays, read about theatre, written about theatre—but it feels like I haven’t touched theatre in so long. I haven’t smelled the dust burning off a Source Four. I haven’t huddled with a crew hours before curtain. I haven’t sat by myself, nestled between strangers and held back tears as a show reached its emotional climax. I was beginning to forget what that felt like. I wasn’t sure if, after a year (or more) I would still be able to do theatre. Would I be out of practice? Am I going to have to fight even more for a spot after not being a practicing artist for so long?

As I took crash courses online and wrote resumes for jobs contingent on the mastery of my backup skills, I wondered if I should pivot permanently away from theatre, from the precariousness of my chosen profession. I know I’m not unique in this—in wondering, “am I a theatre artist when I’m not doing theatre?” Or, after stepping back for a time, wondering “do I still want to do this?”

I wasn’t sure of the answer for a while until I watched The Show That Changed My Life, an interview series produced by Soulpepper Theatre Company featuring theatre artists describing the shows that have had the most influence on them over the years.

It was no surprise, then, that series interviewer and co-curator Frank Cox-O’Connell had been musing on the same questions when he began talking to other artists.

Cox-O’Connell began with the obvious, chiming into the conversation theatre practitioners are currently having en masse: “What is it to be a theatre artist when you’re not actually doing it? When you’re not actually doing it, how do you hold onto it?” For Cox-O’Connell, talking to the artists was a way to get to the source of what drives them to keep working.

For participating artist Akosua Amo-Adem, reflecting on that why was a huge part of the reason she agreed to the series. “The fact that we aren’t currently engaged in it doesn’t erase everything that we’ve done up until this moment. This isn’t the end.” In her episode, Amo-Adem recounts her first professional show out of theatre school and the feeling many artists can relate to: the first time your family sees your work. Going back to the beginning put how far she has come into perspective.

Hearing Amo-Adem’s story, Lorenzo Savoini talking about witnessing levitation, or Jani Lauzon explaining how moved she felt when the Serpent River First Nation community honoured them on tour made my heart swell. That’s why I wanted to do theatre. That was the feeling I was missing. Why had I forgotten it?

Cox-O’Connell echoes Amo-Adem’s sentiment when I chat with him on the phone. With our work being so fleeting, so rooted in ephemera, it can be difficult to stay connected when we’re not actively involved. “We don’t get to take the actual experience of theatre with us and so in some ways it feels like there’s this huge monolith of where we came from but it also disappeared so quickly.”

The rise of theatre in the digital realm takes away some of that etherealness and liveness, but in return, it has allowed shows to be more publicly archived. I’m indebted to everyone before me who grabbed a piece of a show and put it in a book, no matter how much it fails to capture the show’s true essence. The Show That Changed My Life focuses on the emotions, the feelings of theatre that a programme or academic account just wouldn’t have. Cox-O’Connell identified this, too, when putting together the artists’ stories. This contrast between what lives in our mind and what we physically have that represents our work is quite different.

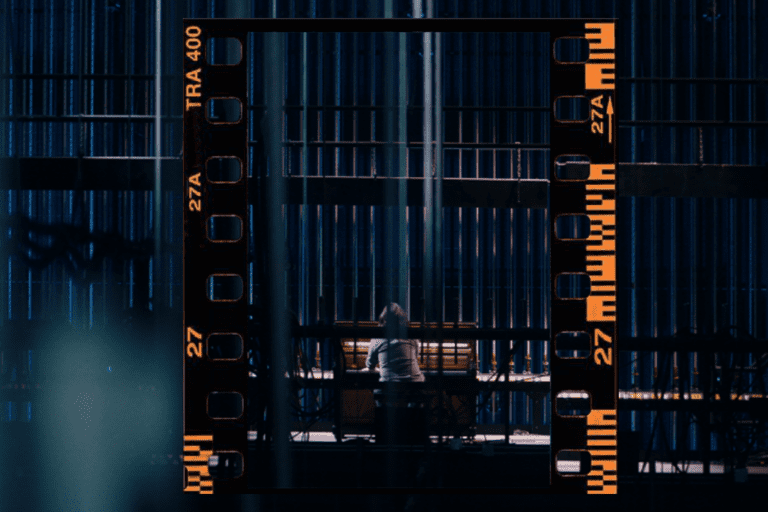

“There was one particular instance where Lorenzo Savoini talks about the moment in a Robert Lepage show where Lepage gives the illusion of defying gravity and describes it in such exquisite detail and talks about crying in the theatre.” Cox-O’Connell tells me, “I found some images of that actual moment and they’re so pitiful to Lorenzo’s passion. I couldn’t bring myself to put them in the video. They just completely fail at capturing what was a life-changing moment for him.”

But there’s much more to the series than purely putting a show on the record. Amo-Adem hopes that people, whether artist or audience, will take this opportunity to connect with artists they may have watched over the years, and take advantage of getting to hear from people who have been in the industry for decades.

“For me, anytime I get an opportunity to hear from someone who has been in this industry for as long as someone like Nancy [Palk] has, it’s always a gift to me. It tells me, as insane as this industry is, you can make it your life. You can raise children, you can have a home, you can do all these things while being a theatre artist because someone like Nancy Palk has done it. That’s the power of it being a video rather than an article printed.”

At this moment where we don’t all have direct access to the thing we love, to making first-hand memories, watching The Show That Changed My Life reminds me that theatre is what we make it. No matter how blurry the picture, how much the stream lags, how many scripts we’ll never see again—theatre is about making us feel something. If all I can do right now as a theatre artist is write and watch and listen, then I’ll remember the feeling that brought me here and I’ll wait.

The Show That Changed My Life series is available in full, online at Soulpepper Theatre’s website.

Comments