In Canadian Stage’s latest project, Brendan Healy ponders his own queer inheritance

In what ways is directing a play like falling in love?

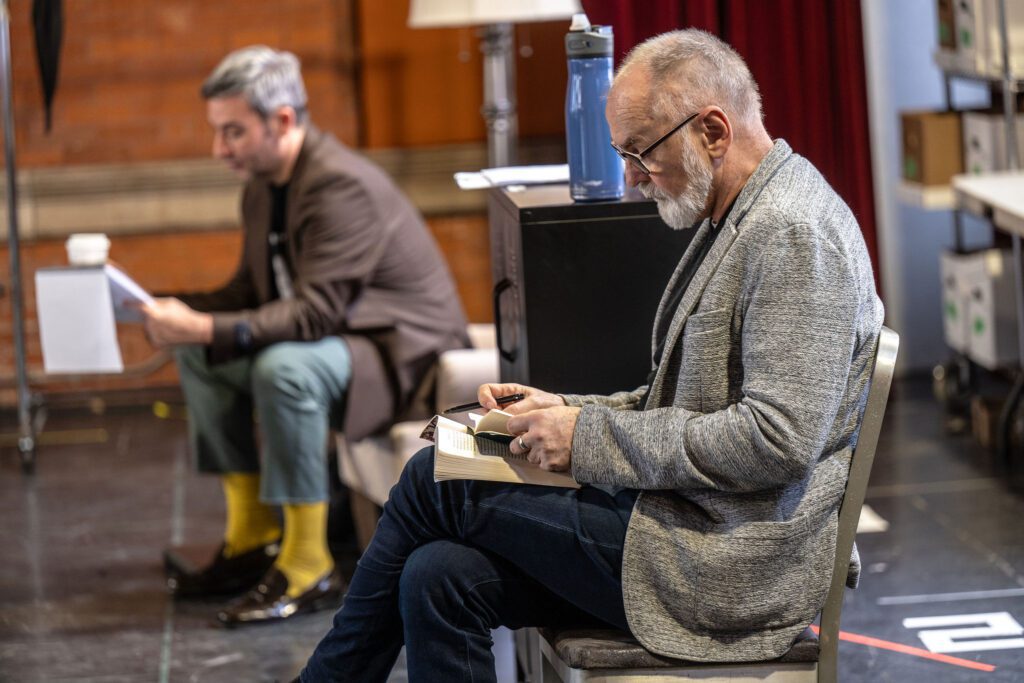

For Brendan Healy, artistic director of Canadian Stage, the two processes aren’t dissimilar.

“[Directing is] a little bit like a kind of erotic attraction,” mused Healy in an interview at the Berkeley Street Theatre. “You sort of get a hit…that grabs your attention. And then you become really interested in the question of… this person [or play] has caught my attention — why? If you’re lucky,” he said, “You get to learn more.”

Healy has spent the past several years asking that question of his current project, which has been in development since before the pandemic: Canadian Stage’s production of The Inheritance, the Tony Award-winning play by American writer Matthew Lopez.

Well, two plays. Inspired by E.M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howards End — a study of uneasy connection between two families with polar opposite views on class, love, and morality — The Inheritance alchemizes the novel into a seven-hour, two-part gay epic, in which multiple generations of gay men must reckon with the legacy of the AIDS epidemic which ravaged the community in the 1980s and 90s, and which continues to cast its shadow today. (In Canada, this legacy is felt in the only-recently-lifted ban on gay men donating blood, as well as in legislation which criminalizes non-disclosure of a positive HIV status.)

Healy, who is gay, was drawn to The Inheritance in large part because of its intergenerational narrative. “Every generation of gay man sees themselves reflected in the play,” he said. “It…touches survivors from that period, touches people sort of like myself, who…came out just as the crisis was ending…and then it also speaks to the realities of people who are young and have actually not lived through any of it.

“That’s really rare,” Healy continued. “A lot of gay stories are very generationally segregated” — something that’s also an issue in the community itself.

Generations aren’t all that divide in this portrait of gay society. The Inheritance also stages a moral battle along fault lines of class and capital, in which the very concept of community is at stake. “There [are] a few characters in the play who are activists,” explained Healy, “and then there [are] other characters in the play… who have a lot of power and privilege, and don’t see their responsibility as being one that includes people beyond their immediate sphere.

“I think [the gay] community… has gained a certain degree of acceptance, and political and economic power, over the past couple decades,” he continued. “The question becomes, as the community ascends in terms of its clout in society, who in that community is left behind?”

In The Inheritance, those in danger of being left behind include the no-longer-living: both the vast numbers of men claimed by the plague, as well as a broader lineage of gay ancestors. Among those ancestors is Forster, the novelist who inspired The Inheritance — and who features as a character in the play.

“I think a lot of people operate in the world in a kind of ahistorical state,” said Healy. “There’s a lot in our society that devalues history and devalues ancestry. So I think the choice to make Forster an actual character in this play was [a choice] to literally put that continuum [of history] on the stage.”

As Forster observes the events of The Inheritance unfold, he offers “the contemporary people in the play… tools to help them tell their story,” Healy shared. “I think that’s what we [in the present day] do: We look to those who’ve gone before us to help us figure out who we are, how we got here, and how to imagine moving forward.”

I couldn’t help but ask Healy about his own queer inheritances.

“One of the very challenging things about being my age,” reflected Healy, “is there’s a generation of men that I don’t have access to. For example, I’m a recipient of the Ken McDougall Award. He’s an artist by all description that I feel is somehow a forebearer of mine, and I feel like I’m somehow part of his legacy; and yet I never had a chance to meet him because he died.” McDougall passed away from AIDS-related illness in 1994.

For Healy, the process of getting to know The Inheritance has also involved a process of self-discovery — another way directing is like falling in love.

“In learning about why, you’re learning about yourself,” said Healy. “What drives you, what fuels your dreams, what fills your imagination.” In this case, he said, “the thing I’m learning is the depth of my sort of trauma around AIDS, which, you know — it’s deep.

“I came into my sexual self in the early 90s, right at the height of the crisis,” he continued. “I assumed that by admitting that I was gay, I would die. [I remember] just being deathly afraid of sex… and at the same time, having the need to connect sexually being more important than the risk… That’s so formative in my sexuality. Time goes by, I’m on PrEP, you kind of forget; but this play is really a deep reminder of how shaped I am by that.”

How does Healy plan to shape The Inheritance — to reckon with the play’s own reckoning with such a terrible legacy of loss? At the end of our interview, we discussed how Healy has approached a moment at the end of Part One — a choice I won’t give away here, except to say that it both honours and defies that loss in a way I can’t wait to experience in the theatre.

“I think the intention of that moment is [linked] to the overall message of The Inheritance,” explained Healy, “which relates directly to Forster’s novel Howards End. The most famous line from that novel is ‘only connect’. That is our purpose as humans. It’s where we find all satisfaction… and I think [The Inheritance] wishes to create connection. Connection to history, connection between generations, connection with oneself.

“So much of the conversation around AIDS is around absence and what we lost,” he continued. “But we haven’t lost everybody. There are survivors and there are people who are living with HIV, thriving. [This] moment is a space for an audience, for a society, to just be with presence.”

Canadian Stage’s production of The Inheritance: Parts One and Two runs from March 22 until April 14 at the Bluma Appel Theatre. Tickets are available here.

Comments