Telling the Story of the Murder Trial that Changed the Country

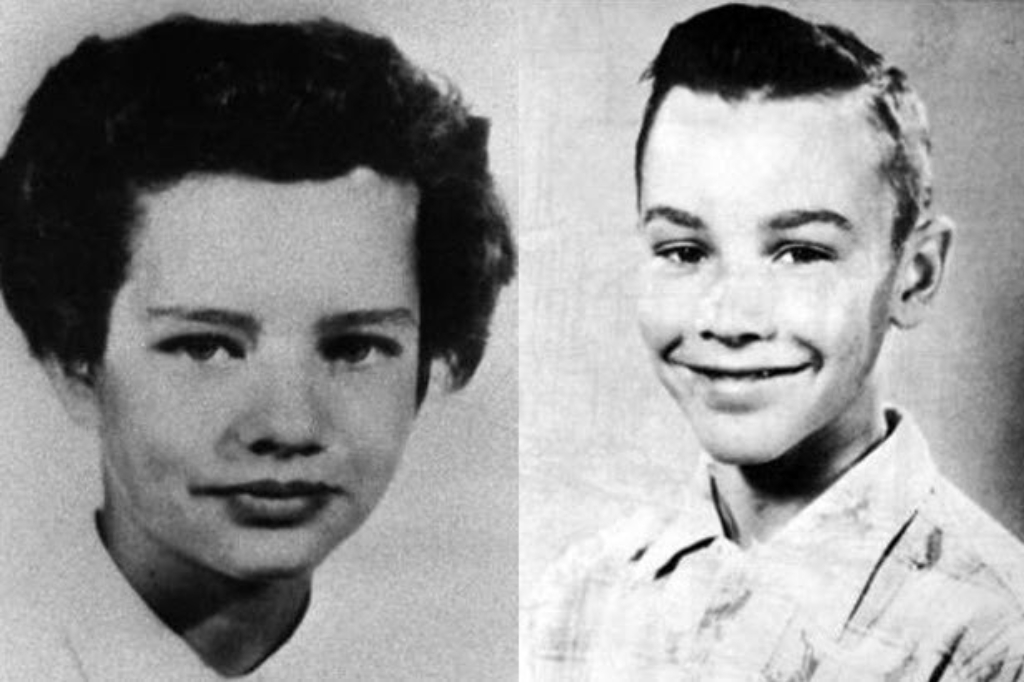

Lynne Harper was a middle child: she had one older brother and one younger. She was small for her age. She was born in New Brunswick, but because her father was in the Air Force, she moved around the country a lot. In 1959, when she was twelve, Harper lived on an Air Force base in Clinton, Ontario, a small town near London. She made lots of friends there—she was an energetic kid, a quality that led some people, looking back later, to describe her as a live wire. Others called her bossy. She was a Girl Guide, and she liked playing baseball. She had crushes on boys in her class and was occasionally self-conscious about a scar on her face from a childhood accident. Sometimes she argued with her parents.

In June of 1959, two months before her thirteenth birthday, Harper was found dead in the woodlot of a farm in her neighbourhood. She had been raped. Her body was covered in cuts and bruises, and the cause of death was strangulation. Four days later, Harper’s schoolmate Steven Truscott, a soft-spoken and well-liked fourteen-year-old, was arrested for her murder and sentenced to death by hanging. His sentence was eventually commuted to life in prison, and he was later released on parole before his conviction was overturned in 2007. Harper’s murder remains unsolved.

Murder trials boil down to observable facts—concrete certainties that have been witnessed and recorded to the satisfaction of a judge and jury. The kind of minutia that otherwise gets lost in the course of an average day—the exact time you left your house (down to the minute!) or the exact colour of car you think you saw your friend walk up to—is elevated to the realm of vital importance. The words we use to describe a conviction or an alibi are words of substance and solidity: strong, bulletproof, iron-clad. The way we talk about a murder charge is at odds with realm of fiction, which is often about ambiguity, emotional states that can’t be easily defined. But when Beverley Cooper wrote Innocence Lost: A Play About Steven Truscott, ambiguity was her chief concern. She believes Truscott was innocent, but the play isn’t really a story about that. It’s about how the community changed after a child was killed and another child was charged with her murder.

Cooper says her friend Ann-Marie MacDonald’s Giller-nominated novel The Way the Crow Flies, also loosely based on Harper and Truscott, served as an inspiration for her when Eric Coates at the Blyth Festival asked her to write a play about the case. She also says she enjoyed the Netflix show Manhunt: Unabomber, a fictionalized take on the FBI’s search for Oklahoma City bomber Ted Kaczynski. “I’m kind of fascinated and yet cautious of that genre,” Cooper says.

Steven Truscott’s parents sit together in silence after learning that the Supreme Court had ruled in an 8-1 decision to uphold the conviction of murder against their son in 1966. They heard the verdict over the radio in a Toronto apartment. Steven heard the news in prison. Photo by Eddy Roworth courtesy of the Toronto Star Photographic Archive via the Toronto Public Library.

Fiction about a real-world tragedy risks sensationalizing the events that remain painful for a lot of people. But they also provide the opportunity to explore human behaviour, to directly address the impacts of violence and trauma. “I think what interests me is not necessarily the crime—I’m not really interested in gruesome crime—but what I am interested in is the social implications,” Cooper says. What fascinated her about this case, she explains, is the effect it had on the community: a small town rocked by unexpected violence, trying to cope with grief and tragedy, divided by what many people saw as competing loyalties to two families suddenly at odds with one another.

The charges against Truscott were laid in large part because everyone agreed he was one of the last people to see Harper alive. He had given her a ride on the handlebars of his bike on the warm June night she disappeared; an immaculate illustration of childhood innocence for two people who didn’t know their childhoods were about to end. (In a rare televised interview from 2015, producers on The Fifth Estate got Truscott to ride by the same area as that fateful bike journey decades earlier. The image was haunting in its mundanity: there’s nothing shocking about a middle-aged man riding a bike until you think about who is no longer there.)

Much of the testimony in Truscott’s murder trial came from children, a detail that seems directly lifted from Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play The Children’s Hour. Many of them gave conflicting accounts, either because they were vindictive or just plain mistaken. The prosecution’s “star witnesses” were Jocelyne Gaudet and Arnold “Butch” George, schoolmates of Harper and Truscott. Both were preteens and both changed their stories to police several times, but neither of those facts stopped prosecutors from putting them on the stand. Neither one has spoken to the press as an adult. But several nurses who trained at St. Mary’s Hospital in Montreal in the 1960s say they knew a woman who called herself Kim, but who everyone knew was actually Gaudet. One nurse said in a signed affidavit that Gaudet had lied on the stand and knew Truscott to be innocent.

Steven Truscott leaving court after his appeal to the Supreme Court, 1966. Photo by Boris Spremo courtesy of the Toronto Star Photographic Archive via the Toronto Public Library.

The fact that so many kids were involved in the trial was another element that was deeply interesting to Cooper. Her son was fourteen when she started writing the play, and she says she remembers looking at him and thinking: How could it happen? “If you think back on a summer night when you were thirteen or fourteen, could you remember exactly where you were or what you did the night before?” she asks. “Something like sixty-one kids were interviewed that night. ‘Where were you, and what did you see?’ The impact of that on the kids, that one of their classmates could be found raped and murdered, and then the guy that they looked up to as the popular jock is charged with her murder—that kind of fascinated me.”

The other big driver of Truscott’s conviction, besides child testimonials, came from science that has since been debunked. Dr. John Penistan, the pathologist who examined Harper’s body, said he could isolate the time of her murder to between 7:15 p.m. and 7:45 p.m., which a doctor named John Butt told The Fifth Estate is an impossible deduction. (Stomach contents tell doctors “nothing precise,” about the time of death, Butt said.) But at the time of the trial, it was enough.

One of the most significant people in the Truscott saga, and one who figures prominently in Innocence Lost, is the late journalist Isabel LeBourdais. She had travelled from Toronto to Clinton in the early ’60s to write a story about the case for Chatelaine, but became so wrapped up it that the article became a book. The Trial of Steven Truscott, published in 1966, was the first major work arguing that Truscott had been wrongfully convicted.

That book is one of many that Cooper read in preparation to write the play. Innocence Lost is meticulously researched, and the majority of the lines that are attributed to real people—like Doris Truscott, Steven’s mother—are either direct quotes Cooper found in the historical record or sentiments she knows the real person expressed. LeBourdais is an exception: her character in the play interacts with characters Cooper made up, so some of her dialogue is imagined. All of Detective Inspector Graham’s lines, Cooper says, come from speeches or interviews he actually gave.

At the time of Truscott’s conviction, some people—even the ones who didn’t doubt that a fourteen-year-old was physically capable of murder by strangulation, like LeBourdais did—rejected the idea that a minor should be hanged. Others, including Harper’s family, believed Truscott did commit the crime and saw doubt in the conviction as an insult to her memory. “Boy seems so calm and normal, but is he savage murderer?” a Toronto Telegram headline asked. When Toronto Star columnist Pierre Berton wrote a poem decrying the decision to put a fourteen-year-old child to death, he received death threats of his own. “A hanging is too good for him,” Berton reports being told by one letter-writer in the Fifth Estate episode about the case. Another person phoned him to say: “I hope your daughter is raped.”

Steven Truscott’s mother Doris with Isabel LeBourdais in 1967. Photo by Eddy Roworth courtesy of the Toronto Star Photographic Archive via the Toronto Public Library.

Wanting someone to blame after such a horrific event is an instinct Cooper investigates in the play, rather than outright condemns. Harper’s death was so shocking, and she was killed in a way that was so gruesome, that it was natural for Clinton residents to find comfort in identifying the supposed perpetrator. “I can totally understand that rush to judgment,” Cooper says. “You so want them to catch the killer right away so that you can breathe again. And if you have children who are the same age, you’re terrified.” She recognizes that instinct in her own reaction to alleged serial killer Bruce McArthur, who police have charged with eight murders in the area of Toronto’s Gay Village. “I believe that guy’s guilty,” Cooper says. “He hasn’t had a trial yet, but I’m pretty certain he’s guilty. And we want to believe he’s guilty, because we want whoever it is who’s doing these horrible things to have been caught.”

More than just the killing itself, Cooper sees Truscott’s story as a loss in faith in institutions that, in the ’50s, many Canadians still saw as faultless. In The Trial of Steven Truscott, LeBourdais wrote that “most of us give very little thought to the manner in which justice is administered. We leave it to the police, the magistrates, the judges, and others involves in judicial processes.” But when it’s a crime news story, and someone gets arrested, people are usually only slightly interested. “We usually take it for granted that the accused is guilty or the police would not have arrested him. We thoughtlessly line ourselves up with the police as judge, jury and even executioner.”

The continued and contemporary need to be vigilant about our justice system is something that came up often in the play’s rehearsal hall with director Jackie Maxwell, Cooper says. We are still learning about institutional problems that disproportionately punish certain groups while criminalizing others, she says, pointing to the recent acquittal of Gerald Stanley, the farmer who fatally shot twenty-two-year-old Indigenous man Colten Boushie in Saskatchewan. (Boushie’s family has recently asked the UN to investigate systemic bias in the way law is enforced in Canada.) “Our justice system is enforced by humans, and humans are by nature fallible,” Cooper adds.

Cooper met Truscott briefly when he came to see the play during the last show of its run at Blyth. Just before the play started, a girl who looked about twelve went up to Truscott and asked for his autograph. His legacy, though, remains mixed: Cooper says a previous artistic director at Blyth received death threats when he suggested a play about the case. For her part, Cooper was impressed by Truscott. “He was so gracious, and so polite, and kind of shy,” Cooper remembers. “I found it so incredible that he could go through all this and not be bitter.” He rarely gives interviews, and has since changed his name. He has a wife and grown children, and is now a grandfather.

Berkley Silverman as Lynne Harper and Dan Mousseau as Steven Truscott in Soulpepper’s Innocence Lost. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Over the years, many other people have been considered as possible suspects in Harper’s murder. In Until You Are Dead: Steven Truscott’s Long Ride into History, author Julian Sher lists suspects, including an Air Force sergeant named Alexander Kalichuk, who had been caught trying to lure a ten-year-old girl into his car the month before Lynne was killed. Police never considered him a suspect. Clayton Dennis, an electrician on the Air Force base who was a convicted rapist, was never questioned by police. Matthew Meron, a lifeguard who was nineteen at the time of Harper’s death, later sexually abused his young daughters and tried to strangle one of them. And several years ago, retired Ontario Provincial Police officer Barry Ruhl published a book called A Viable Suspect about a different man, whose real name he doesn’t use, a suspect in an unsolved early ’70s murder of a teenage girl. “We’ve got all sorts of cold cases in Ontario,” Ruhl told a Guelph Mercury reporter in 2014.

For Cooper, a major priority was making sure Harper isn’t forgotten from the play. It was important to her that a young girl play Harper for the few scenes she has in the play, rather than an adult actress. “When you see that innocence in that child, it hopefully has some resonance,” Cooper says. She wants Harper’s casting to be “a reminder to us that this did happen to somebody so young, and that it was a very tragic thing. I think we can get lost in details of legal stuff and crime stories.

“It always seems so cold when they tell it—the newspapers, and then lawyers and then the books. Like her death was just a pile of details to be examined,” says one of the characters in the play. “She was a living, breathing twelve-year-old child. She was a good girl.”

Comments