In Morris Panych’s Withrow Park, the mysteries of the universe come knocking

Morris Panych’s surreal new play promises to be anything but a walk in the park.

The play, directed by Jackie Maxwell at Tarragon Theatre, follows three characters in their sixties: Janet (Nancy Palk), her sister Marion (Corrine Koslo), and her ex-husband Arthur (Benedict Campbell). The trio co-exists in an old Edwardian house overlooking Withrow Park, located just south of Danforth Avenue in Toronto. Arthur has recently come out as gay and left Janet for another man — only to be left himself in turn. Marion, meanwhile, toys with the possibility of ending it all.

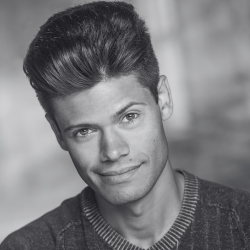

Despite these complications — and unlike the gentrifying park outside — the trio’s lives remain stagnant. They talk in circles, get on each other’s nerves, and lament their banal existences, until one day a mysterious stranger (played by Johnathan Sousa) knocks at the door.

Panych, unlike the characters in Withrow Park, is trying to avoid stagnation. At 71, the two-time Governor General’s Award winner is “obsessed with the idea of how much is left and what to do with that time.”

“That’s really a big part of what drove this play,” he said in our interview.

In Withrow Park, these questions arrive courtesy of Simon, the stranger at the door. “I often, in my plays, introduce an outsider who nobody seems to know,” said Panych. It’s difficult to say too much about Simon without spoiling the play, but suffice it to say his arrival provides a much-needed jolt to Janet, Arthur, and Marion.

I think the best kind of writing leaves a lot out. It takes away, it leaves space for thought and theorization. It creates more drama for the audience.”

Morris Panych

The characters in Withrow Park “have such little problems,” explained Panych. “They’re probably fixable, or maybe not fixable, but who cares in the larger picture? That’s why this character comes along. He’s like, there’s this fucking universe out there, there’s Orion, this is nothing.”

The meaningless of the everyday, combined with the promise of something both more absurd and more sublime — this, too, is a hallmark of Panych’s work. At the same time, the ways in which Panych investigates those themes have shifted in recent years, thanks in part to his extensive experience as a director. He often directs his own work.

“My early work [as a playwright] was very quick and sharp, and really absurd”, said Panych. “As I started to move on — I don’t like to use the word depth, because I really hate that word — but it started to go in a different direction in terms of the thought processes of the characters…I absorbed a lot of feedback I was getting from actors [about] their difficulty accessing the material.”

When he started to write “a slightly different kind of play” in response to this feedback, he found it “satisfying, and in some ways more moving.”

On the other hand, Panych said he’s told the actors in Withrow Park not to go “too Stanislavski” on the play, “because it’s really operating on a more metaphorical level.”

“All the same,” he explained, “I respect that they have to do that work, because they have to make it make sense for them.”

The world of Withrow Park certainly doesn’t stay Stanislavskian for long. Gorgeous, otherworldly monologues rend the fabric of everyday interaction. A body in a morgue speaks. I asked Panych about his enduring love for the absurd, and the darkly comic. “Clearly I have a very twisted and perverted perspective,” he quipped. “Not very, but a little. I don’t necessarily trust reality.” He mentioned that “growing up as a gay person in a pretty straight world…I found my life very absurd.”

“Also, my parents were very ironic…I mean funny, but very dark. But also the world is dark. When you look at the world and the way it operates, it is absurd.” Panych said that in his plays, he tries “to find the grain of truth inside of that” absurdity.

Clearly, I have a very twisted and perverted perspective…not very, but a little. I don’t necessarily trust reality.

Morris Panych

Panych’s love for the surreal and metaphorical is one reason why Jackie Maxwell is the perfect director for Withrow Park. Maxwell “sits inside things in a way that I don’t, really”, said Panych. “I’ll often work from the outside in. A lot of my thing is musicality, and the shape and sound of words. Jackie trusts the shape of what I’ve written and tries to find the nuance inside of that.”

“She’s Irish, which I think helps,” he joked. “Because she probably understands Beckett, and I’ve created a world where people are stuck in this vacuum.”

Panych stressed that he is conscious of trying not to over-explain the play itself, either for the creative team or the audience. “I think the best kind of writing leaves a lot out,” he said. “It takes away, it leaves space for thought and theorization. It creates more drama for the audience.”

Withrow Park certainly leaves space for the audience to think and theorize: the questions at the centre of the play have no easy answers. Panych said he is trying to explore, “not [an] afterlife, because I don’t really think there is one”, but that which is “beyond what we experience and live right now in our own lives…that makes our lives more present and more meaningful.”

In our conversation, Panych recalled a personal moment in which he was confronted with a more meaningful vision of life. In the late 80s, at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, “there was a doctor in Vancouver, Dr. Peter [Jepson-Young], and he was dying of AIDS,” shared Panych. Every week, in a video diary for the CBC, Dr. Peter “talked about dying…about the body disintegrating.”

Panych remembers seeing The Dr. Peter Diaries on television. “It was so profound and so courageous, like, ‘This guy is seeing way beyond his life right now. He’s seeing something much bigger.’ That always stayed with me. I always thought that was what the best of human existence should be.”

This “seeing beyond” echoes in a particularly surreal scene in Withrow Park, involving Sousa’s mystery-man. “One of the most important things to me,” Panych said of this scene, “is that people understand that flesh is meaningless…In the whole history of the world it’s never going to change. We’re always going to be flesh and blood — until AI takes over — and [flesh] will always be meaningless, because it’ll go away. It’ll be temporary and transitory.”

This lack of permanence was once something Panych feared. “As I got older, I started to get scared about my body disintegrating,” he said. Then he remembered Dr. Peter.

“I went back to thinking about him and thinking, you know, I really have to enjoy this. I really have to enjoy this slow disintegration.” He has no desire to be one more “grouchy old man in the SUV”, he says. “There’s a lot of those out there.”

Withrow Park opens at Tarragon Theatre on November 15 and runs until December 3. You can purchase tickets here.

Comments