REVIEW: Mononk Jules is a powerful exploration of Indigenous Canadian history that asks more questions than it answers

What parts of us are recorded by history, and what parts of us are forgotten, even by family? These questions come up in the first few minutes of Mononk Jules, a one-person show at Théâtre français de Toronto, when writer, director, and performer Jocelyn Sioui notices that some documents are missing from the family’s fabled banker box of ephemera about his great uncle Jules. Jules was an Indigenous activist – a genuine hero known for his tirelessness, righteous rage, two hunger strikes, and later, in his town, for his erratic and violent behaviour.

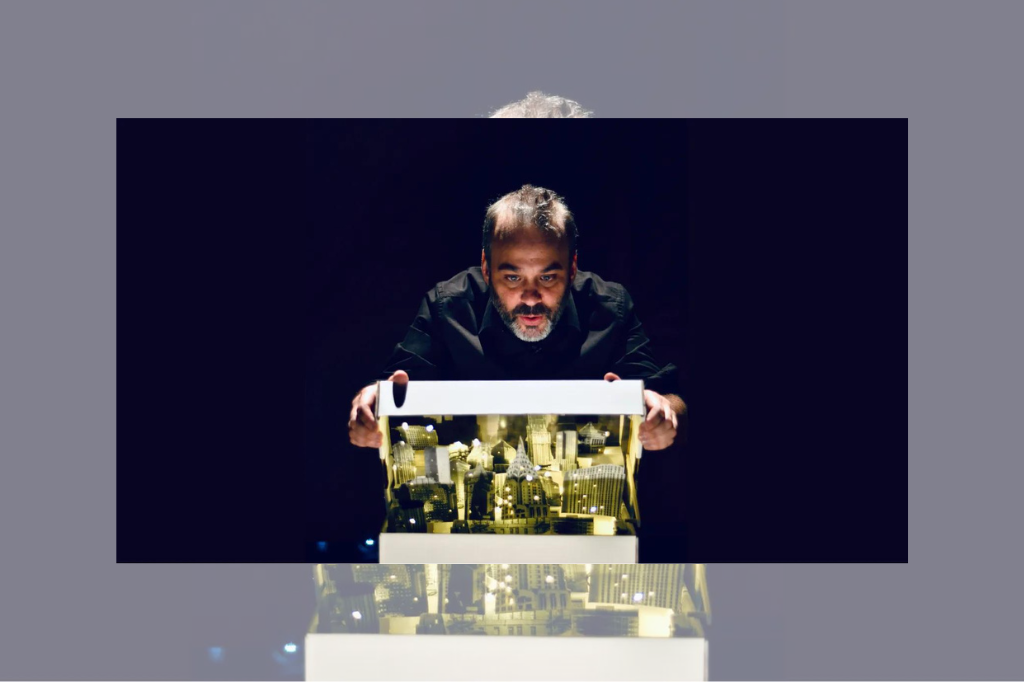

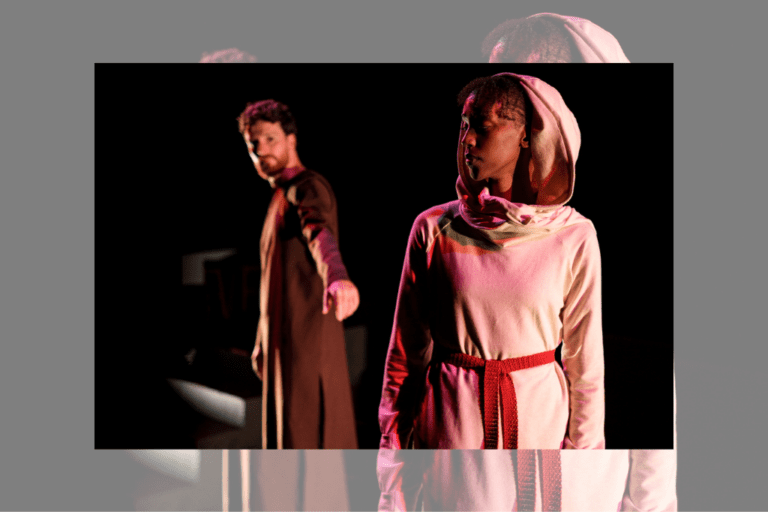

Throughout the two-hour show produced by Illusions Fabuleuse, Sioui revisits the life and legacy of his great uncle through a personal and political lens, tracing the history of Indigenous oppression and resistance with a focus on the Wendat people and the Wendake reserve near Quebec City. He tells the story through puppets, video clips, scanned documents, and animation. The stage is lined with banker’s boxes, ubiquitous and utilitarian objects from which Sioui lifts a family of puppets or which, when turned over, reveal the model of a city or room – glittering miniature worlds and powerful traces of suffering. Sioui is a puppeteer as well as an author and performer, and he uses that craft in ways both humorous and heartbreaking, as with a cut-out of his mother which has evasive googly eyes and a sly smile, and an emaciated puppet version of Jules on his second hunger strike, which Sioui cradles like a child.

Some of these banker box models are more successful than others, and some feel a little disproportionate to the story. There is an incredible moment when a box opens up to a model of New York City which Sioui explores with a hand-held camera (he lifts the facade of one building to reveal an opera house, cue a snippet from an opera performance) but Jules’ time in New York is less than a blip in the plot. Sioui is a warm and entertaining presence, speaking at a rapid-fire pace (non-French speakers may have difficulty following the surtitles) and addressing his audience openly. While some participatory elements were a little awkward, this only added to the powerful intimacy of the show.

Throughout the piece, Sioui explores how settlers have made systematic efforts to erase and suppress Indigenous culture. He asks why significant Indigenous leaders (like Kondiaronk, a Tionontati chief who brokered the Great Peace of Montreal in 1701) are absent from our history books, while white politicians whose deeds run from regrettable to abhorrent have bridges and streets named after them. But more difficult to explain is why Jules’ own community disavowed him. Why has someone who spearheaded the historic 1943 meeting of Indigenous Chiefs and Parliamentary officials in Ottawa (the first of its kind in 50 years), and who captured national attention with his hunger strikes and Supreme Court case for seditious conspiracy, left so few traces? And why did Sioui’s parents remove a few documents from the banker’s box?

The answer is a gutting twist which I won’t spoil, but which makes Sioui’s story genuinely unforgettable. After a rousing and righteous survey of Indigenous resistance, Sioui’s show tips into something more mysterious and uneasy, into the unexplainable darkness of the soul. At the performance I attended, Sioui mentioned he has performed Mononk Jules over 95 times, but there was nothing cursory or fatigued here. This was a powerful, deeply-felt performance about the treacherous but necessary work of tracing personal and political histories.

Mononk Jules runs at Théâtre français de Toronto until March 23. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission‘s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission‘s partnership model here.

Comments