REVIEW: The Queen In Me at Nightwood Theatre/Canadian Opera Company/Amplified Opera/Theatre Gargantua

When you hear the Queen of the Night sing her infamous “Der Hollë Rache” aria in Mozart’s Magic Flute, the piercing high Fs typically coincide with the visual of the feisty coloratura soprano in her sultry black dress and darkened, haloed costume. Yet, Teiya Kasahara 笠原貞野, creator and performer of The Queen In Me, alongside co-directors Andrea Donaldson and Aria Umezawa, say that there is much more at stake for the person behind the high notes, and certainly more for the Canadian operatic industry.

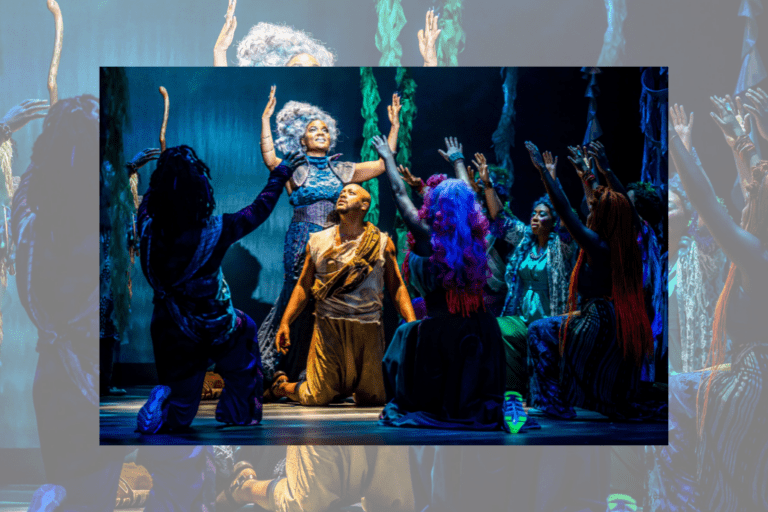

In this 75-minute, one-handed opera performance, Kasahara, accompanied by music director David Eliakis, tear open the truth of being a trans, non-binary soprano in the Canadian opera landscape. Summoning the Queen of the Night, Kasahara begins the performance with the iconic “Der Hollë Rache” aria. However, not long into the demanding tessitura of the piece, Kasahara halts their singing to begin the performance of what they came to do. Rooted in selfhood and identity, Kasahara performs captivating renditions of recognizable, canonical soprano arias. From song selections from Puccini’s La Bohème to Verdi’s Macbeth, among others, performed by Kasahara, the pieces included in The Queen In Me depicts key moments of operatic characters who find themselves in precarious states of crisis in their respective narratives. Alongside the robust and undeniably stunning vocals, this performance is full of witty enriched dialogue in which Kasahara calls out the opera Industry for its expectations of sopranos, women, racialized, trans, and non-binary folks.

Pedestaled on a platform, Kasahara remains still and poised throughout the performance, showing true resilience and defiance to anyone who claims their presence is not welcome in opera. Kasahara in their recognizable Queen of the Night costume, designed skillfully by Joanna Yu deconstructs this iconic character, and strips away (literally!) everything that is recognizable about the Queen of the Night to reveal a refreshingly truthful portrayal. But, more so, Kasahara reveals the fluidity of these century-old canonical characters. In other words, selfhood and identity should not need to be in question in order to play a role — instead well-loved operatic roles can adapt, posits The Queen In Me, and they are capable of being self-affirming roles for artists.

Kasahara effectively builds suspense by narrating the trajectory of their career as a coloratura soprano in an industry that is alien to their identity as a trans, nonbinary, bi-racial person. The replicated curtained proscenium theatre, designed also by Yu, perfectly frames Kasahara as the Queen of the Night, trapped in their narratives and storyline, but unleashed and with more than enough to say.

The Queen In Me enchantingly criticizes the ongoing exclusivity of opera in Canada and reveals the truth of what it is like for Kasahara to have had to remain performing in hyper-feminized and limiting roles. Moreso,The Queen In Me identifies the current pain and feelings of misalignment of operatic characters who are time and time again revitalized, played, and one-sided.

How are trans, nonbinary, and cis women opera singers today affected when operatic characters made for their voice type have remained virtually stagnant over centuries? Well, The Queen In Me answers this question and more. The Queen In Me is a radical, innovative piece of operatic art. This work does more than just make suggestions to the Canadian opera community. As Kasahara and pop singer P!nk would put it: “it’s not anything but loud.”

It is no longer enough for operatic pieces to claim innovation because they are set in an unconventional space, or be praised for the “bravery” of modern costume and lighting. Instead, The Queen in Me cautions the operatic industry that trans people, nonbinary people, and cis women are tired of playing double agents in their lives and careers. The characters they play are usually deemed disposable in their narratives as they wait to be saved, killed, hurt, or, in a comedy – married. Through the autobiographical nature of The Queen In Me, Kasahara suggests that offstage, operatic singers deemed suitable for these roles are expected to behave and act well mannered (or, heteronormative and white) to stay in the industry and continue to be cast.At its core, The Queen In Me is a hilariously cathartic piece of operatic work with unique aesthetics, mesmerizing projections by Laura Warren, and clever set and costume design. Yet even more so, The Queen In Me is a vulnerable call to the operatic industry fiercely urging those in leadership roles to advocate for the alignment of selfhood and character in an art form that seems sometimes unwilling to budge or move.

You can find out more about The Queen In Me here.

Comments