REVIEW: The Secret to Good Tea balances poetry and humour at London’s Grand Theatre

The secret to good tea is the people you share it with and the space it opens for story.

Such is the central conceit of Rosanna Deerchild’s The Secret to Good Tea, co-produced by the Grand Theatre and National Arts Centre (NAC) Indigenous Theatre, and directed by Renae Morriseau. As the play’s program notes explain, Deerchild’s work emerges from a promise to her mother — a residential school survivor — to share her story, and what the playwright describes as the desire to “have a larger conversation about what intergenerational trauma looks like and how we reconcile that within our own families.” From my own positionality as a settler Canadian, the play offers deeply personal insights into under-acknowledged aspects of Canada’s colonial past and present.

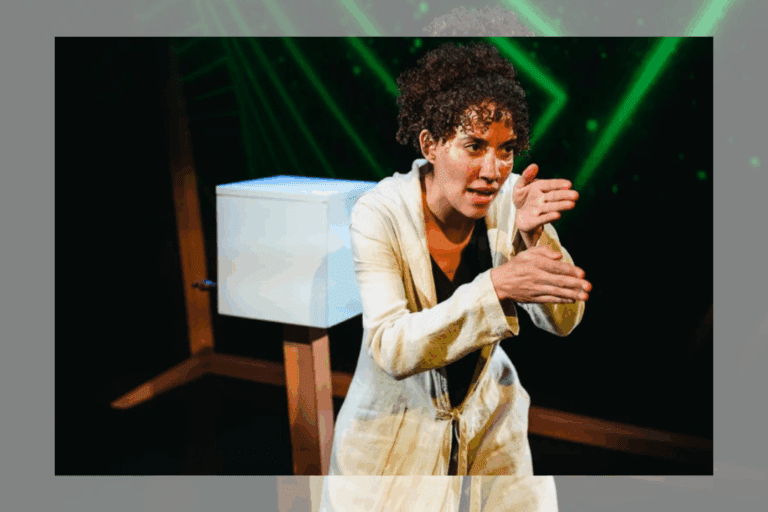

The play centres up-and-coming radio host Gwynn Starr (a brightly sarcastic Michelle Bardach) and her mother Maggie Mooswa (Marsha Knight). When a gathering is planned for survivors of the residential school Maggie attended, Gwynn wants to produce a documentary and share her mother’s story, but Maggie is hesitant to revisit the memories and trauma she associates with the place.

Through many conversations held over tea, the women navigate the ways in which the legacy of the residential school system has shaped their relationships — with motherhood, within their marriages, and ultimately with each other. These conversations are interleaved with scenes featuring the supporting characters of Gwynn’s husband (James Dallas Smith), friend (Kelsey Kanatan Wavey), and radio producer (Jeremy Proulx), a community that highlights the complex, interrelated, and deeply personal realities of colonial violence. Emily Solstice Tait’s dynamic Crow (with choreography by Montana Summers) lingers on the outskirts of this community for much of the play, as the intertwined figure of Maggie’s mother and her trauma.

Deerchild is perhaps best-known for her journalism (she hosts CBC’s Unreserved) and poetry, and that poetic voice shines in the play’s monologues, appearing alternately as Maggie’s nightly prayers and one-sided conversations with Hank Snow, whose songs fill her kitchen from a tiny radio. Delivered with care and a raw intensity by Knight, these moments give the play a strong emotional core, and balance well with the script’s sharp humour.

The play is also visually beautiful. The first act’s set is clever, with set pieces rotating and unfolding to transform from cosy kitchen, to bedroom, to radio studio, and back again (no specific designer is credited in the program or on the Grand’s website). Mural-like imagery of falling crow feathers — a nod to Tait’s Crow — also lends the set a metaphorical weight. Cande Andrade’s projection design immersively invokes Maggie’s nightmare-scape, complemented by Olivia Wheeler’s sound design and Tim Rodrigues’ lighting (projections have become a common feature in recent Grand productions — 2023’s Controlled Damage and January’s Heist especially come to mind).

The cast’s construction of a tipi followed by a smudging ceremony in the play’s second act offer the audience an extended opportunity to reflect on both the stories shared and the journeys the characters have taken to be able to share them.

But there are moments where the play and production don’t feel fully settled into themselves. There is room for the onstage relationships to deepen, for dialogue to flow more smoothly, and for pacing to become more fluid. On opening night, the piece ran just shy of three hours (including intermission and a welcome speech), and seemed to struggle to fill that time — repeated narrative beats made some sections of dialogue feel stretched out, while other elements of the plot (like the internal and external conflicts Gwynn faces over sharing her mother’s story) would benefit from further development. Perhaps some of these details will iron themselves out as the play continues its run at the Grand (before transfering to the NAC in March).

The Secret to Good Tea’s content is necessarily heavy, but the Grand’s production is highly attentive to community care: the theatre offers spaces in its lobbies where audience members can reflect, take time to process, or find further resources. It also provides fairly detailed content warnings in programs, pre-show emails, and posted signage. That said, a couple of additional notes may have been helpful — there is no warning, for example, regarding an intense discussion of domestic violence near the end of the play’s first act. The aforementioned smudging ceremony also sees smoke travel throughout the theatre space — given the Grand’s pre-show notes about other sensory elements of the performance, a heads-up on this may be useful for some audience members.

While a few adjustments could heighten the play’s impact, The Secret to Good Tea remains a deeply personal look into Deerchild’s family history, with implications that speak to the long-lasting and widespread impacts of colonial violence. It’s an undoubtedly important piece of testimony, shared here with warmth and care.

The Secret to Good Tea runs at London’s Grand Theatre until March 8. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments