REVIEW: Tennessee Williams deep cut Summer and Smoke warms up Crow’s Theatre

I can’t decide whether it was a stroke of genius or minor self-sabotage for Crow’s Theatre (co-producing with Soulpepper Theatre in association with Birdland Theatre) to program Tennessee Williams’ Summer and Smoke, a play suffused with suffocating heat, during the dead of a Toronto winter. As I bundled myself inside and loaded the straining coat rack, the idea of a claustrophobically humid summer never seemed so far away — or, conversely, so appealing.

Paolo Santalucia’s production offers up heat in the midst of austerity, setting the romantic tragedy of missed connections in the round on a forbiddingly dark stage. A curvaceous statue of a headless angel, some descending greenery, and a few pieces of turn-of-the-century wood furniture are set and lighting designer Lorenzo Savoini’s main concessions to the organic life and decay that permeate most of Williams’ Southern Gothic works. While these directorial and design choices add challenges in surmounting the deep freeze outside, there are still enough flashes of fire in the show’s portrayal of star-crossed lovers to melt a heart.

Summer and Smoke doesn’t get aired out as often as Williams’ heaviest hitters, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. It has all the Williams hallmarks: doomed love, smothering parents, women on the verge of a nervous breakdown, and men acting out self-destructively to avoid introspection. But even Williams didn’t think it was his strongest, eventually rewriting the 1948 play entirely in 1964 as The Eccentricities of a Nightingale.

“I don’t think I will be able to get through the summer,” nervous, fluttering preacher’s daughter Alma Winemiller (bahia watson) repeats to John Buchanan, Jr. (Dan Mousseau), her childhood neighbour in Glorious Hill, Mississippi, upon his return from medical school. Alma’s name, the play relentlessly mentions, means “soul,” while John’s is associated with baser desires.

The two become locked in a painful courtship and a philosophical battle of what’s truly real — the spirit or the body — as Alma decides whether to give in to her attraction and John seems determined to squander his professional reputation on alcohol, women, and gambling.

As Alma, a beacon of purity appropriately wearing layers of white lace (beautiful costumes by Ming Wong), watson employs a high-pitched, rambling chatter and a childlike, hiccupping giggle to create the impression of a delicate moth. Mousseau’s the intense flame that constantly singes her wings.

Their frustration at their inability to connect is palpable. Like a proto–Sandy and Danny from Grease, the good girl and bad boy try to change each other and leave indelible marks — but here there are no flying cars to sweep the tortured pair into the sunset, only the lingering regret of asymptotic lives that never fully intersect.

Speaking of asymptotic, Mousseau is strongest during his transformation in the second act, and watson’s strongest in the first (when Mousseau is still warming up) and epilogue, with her change of heart being more of a mystery. But both are quite captivating, exploiting Williams’ long, emotional speeches to encourage us to feel deeply for these profoundly flawed people.

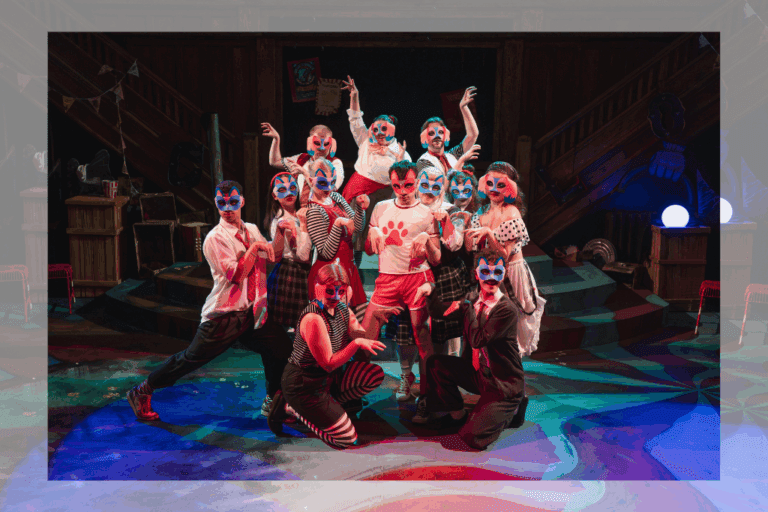

They’re up against aspects of Savoini’s design, ironically reminiscent of his hazily lit, monochrome, and distancing set for last year’s also seasonally titled Winter Solstice from Necessary Angel Theatre Company. Luckily, Santalucia’s direction has plenty of life, passionately playing outward to all sides of the audience. The in-the-round aspect still brings challenges that are often but not always conquered, with the occasional scene sitting stagnant as a windless July day or rotating quickly enough to make us dizzy as a Southern belle with the vapours. It also disjoints the aural cohesion of the musical interludes where the cast sing and play instruments — sometimes to remind us of Alma’s attempts to rise higher through song, and sometimes to capture her nervous heartbeat — because the vocals and instruments are distanced around the stage’s edges.

Among the ensemble, Bella Reyes does strong work as both Alma’s sweet but untalented music student Nellie and John’s fiery lover Rosa, who rises from plot device stereotype with a striking monologue in the second half. As the elder Dr. Buchanan, Stuart Hughes provides a kindly source of refuge otherwise in short supply.

Amy Rutherford raises an unsettling spectre for Alma’s potential fate in her role as Mrs. Winemuller, whose mental state resembling a defiant, sulky child pushed Alma to become a caretaker too young. Her treatment is a sobering reminder of how societal rules persist in caging vulnerable people who refuse conformity, with those in power labelling any demand for equality as defiance.

Rutherford is equally pitiable and menacing as Mrs. Winemuller offers unwanted commentary and rages over being forced to solve a jigsaw puzzle with pieces that don’t fit. Her intrusive, harsh laughter is the antithesis of watson’s nervous, breathy giggles, and her presence provides clarity as to why Alma works herself into heart palpitations trying not to take up space.

In a pivotal moment, Alma compares the lines of a gothic cathedral to the human aspiration to reach up for something greater, the building’s delicate luminosity countering its hard lines of stone. Looking up at the trailing greenery and risen statue, after the first scene tucked near the ceiling, I wondered if further following that directive to push upward instead of outward, balancing the corporeal dark with a little more spiritual lightness, might have made this ambitious and heartfelt production spark just a little bit hotter.

After all, summer heat rises.

Summer and Smoke runs at Crow’s Theatre until March 8. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments