REVIEW: Talk Is Free’s Company is valiant but imperfect

Company, Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s Tony Award-winning 1970 musical, was trailblazing in how it dealt frankly with modern marriage, divorce, and sex. More a series of vignettes than a plot-driven show, it revolves around Robert (Aidan deSalaiz), who is turning 35 unmarried (gasp!). His coupled-up friends throw him a surprise party while pestering dear old Bobby to finally make a commitment.

Revivals of Company often make intriguing tweaks to the original. I fondly remember John Doyle’s 2006 Broadway version that had the characters playing instruments as an extension of their personalities; Marianne Elliott’s 2018 West End production (which then played Broadway and toured North America) gender-swapped several characters to wide acclaim.

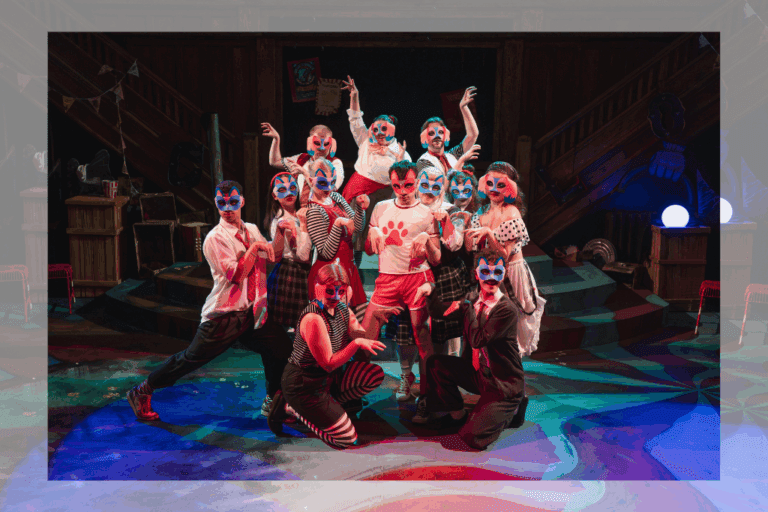

While Talk Is Free Theatre has a reputation for immersive, site-specific theatre, and director Dylan Trowbridge sometimes populates the aisles with actors, this Company at The Theatre Centre is a surprisingly conventional mounting of the show. That’s not necessarily a bad thing; the straightforward staging, the period costumes and hairstyles (by Varvara Evchuck), and Rohan Dhupar’s Swinging Sixties choreography (with plenty of coordinated arm movements for subway straphangers and partygoers) give off an enjoyably throwback vibe.

There are elements of Company that are timeless, such as how we grapple with the need for connection. Furth’s script, full of incisive human paradoxes, still resonates in an era where the enormity of choice in relationships makes them feel both exciting and transient: like the subway, if this doesn’t work out, there’s another coming in five minutes. There are also references and sensibilities about romance that mark Company as a period piece, some of which the authors updated in a 1995 revival but later rescinded.

When the show embraces this period aesthetic, leaning on Sondheim and Furth’s humour in the arc of each vignette, it’s crackling and fun, with entertaining ensemble numbers and some standout performances. As of opening night, the show was still finding its feet in conveying the overall arc, handling the big emotions and realizations that stem from these capsule moments in Bobby’s life. It’s an entertaining staging that, like its central character, is still waiting to completely connect.

The production skilfully strips down Sondheim’s fiendishly difficult score to a dynamic duo of onstage piano (music director Stephan Ermel) and violin (Aaron Schwebel, at the performance viewed), whose presence the actors occasionally acknowledge.

Aiming to evoke the characters’ wealth and taste through minimalism, set designer Varvara Evchuck has given the Franco Boni Theatre a similarly stripped-down aesthetic, providing a few party lights, an upstage runway-style platform where Bobby’s friends and conquests enter and cavort, as well as a couch and drinks cart that the actors efficiently maneuver during transitions.

The large, black space of the relatively unadorned theatre feels cavernous here, and Trowbridge employs it better during scenes on lonely, rarely used apartment terraces and the show’s iconic number about the ever-changing, bustling facelessness of the city (“Another Hundred People”) than he does in smaller, more intimate scenes where Bobby discovers that three’s a crowd.

With this austere backdrop, it’s harder to convey enough warmth to balance that creeping maw of loneliness, and it’s harder to balance the audio, too; sometimes, a little judicious microphone use would go a long way toward making each of Sondheim’s delicious, rapid-fire lyrics crystal clear.

Speaking of austerity, the sympathetic but underwritten Bobby is always by necessity more of a reactive character than a proactive one, constantly under the microscope of his contrastingly forceful posse. This gives deSalaiz a difficult task in trying to create a character that’s both a reflection of how his friends perceive him — a sunny, serial charmer — and how his more interior and introverted lyrics portray him.

deSalaiz leans into the latter, giving us a Bobby who’s withdrawn and reserved to the point that it’s sometimes difficult to understand how his friends got that former impression. Further balancing these sides of Bobby might lead to a clearer sense of his journey toward a decision on whether to let someone into his life on a permanent basis.

When deSalaiz gets a chance to be an equal partner, or even has the upper hand, such as a scene between Bobby and casual girlfriend April (Maggie Walters) where he wars between genuinely revealing himself and having a one-night stand, he rises to the occasion, compellingly rounding out the character.

It helps that Walters soars in the role as the self-professed dumb, flighty flight attendant, commanding attention with quirks such as pointing out elements of the décor of Bobby’s apartment as though she’s gesturing to emergency exits on a plane.

Other cast standouts include Shane Carty sharing wrestling moves and soulful tunes as recovering alcoholic Harry, Jamie McRoberts sailing over the high Cs as southern belle Susan, and Sydney Cochrane navigating the most difficult, rapid-patter piece of the evening as nervous bride Amy (“Getting Married Today”). Gabi Epstein as blowsy Joanne makes the biggest impression, gleefully chewing the scenery and downing vodka stingers while spitting out a couple of ex-husbands; she delivers Sondheim’s blisteringly judgmental “Ladies Who Lunch” with potted panache.

Overall, Talk Is Free’s Company is a valiant if imperfect production. But then, being vulnerable enough to let someone in means accepting that you’ll make mistakes; the hope is that they’ll love you anyway.

Company runs at The Theatre Centre until February 8. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments