REVIEW: Women of the Fur Trade at the Stratford Festival

Louis Riel is SO dreamy. Tall. A little disheveled and unkempt, because he’s an introspective poet who’s busy fighting for social justice. And he wears glasses. He’s the total package.

At least that’s what a young Métis Marie-Angelique (Kathleen McLean) believes in Frances Koncan’s uproarious Women of the Fur Trade, directed by Yvette Nolan at this season’s Stratford Festival. Cecilia (Jenna-Lee Hyde), a married settler woman, finds Riel’s assistant Thomas Scott to be quite the heartthrob, but the free-roaming, fur-selling Ojibwe Eugenia (Joelle Peters) knows they are both a bit misguided.

The trio find themselves stuck in a fort together in Treaty One, on the banks of the Reddish River as the British advance and confederation becomes increasingly inescapable. Unable to go anywhere, they work, gossip, and write letters to the outside world.

Riel (Keith Barker) is on the path of resistance with Scott (Nathan Howe) tending to his correspondence. After receiving a letter from Marie-Angelique, Riel, tired of fan mail, leaves Scott to respond. Scott is smitten with Marie-Angelique, and begins a pre-confederacy catfishing expedition. Believing she’s exchanging letters with Riel, she’s inspired to escape the fort and fight on behalf of the Métis and First Nations.

Steeped in historic fact, Koncan’s political rom-com trades the omnipresent colonial male gaze for that of Indigenous women, and uses more a contemporary colloquial vernacular (clearly one I don’t speak fluently but understand it when I hear it). The effect is a kind of timelessness, one where each character and their humanity are immediately recognizable. Their conversations, in reality, would have sounded quite different, but they still would have gossiped, laughed, and fought about politics and religion while literally holding down the fort — the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Koncan’s sense of humour is irreverent and Nolan’s equally playful direction compliments it, creating a disarming atmosphere where the audience can investigate some dark history and its fallout without shame and defensiveness. Though themes of racism, misogyny, and the complexity of living in pluralistic groups with competing interests are overtly addressed, it never felt preachy or heavy handed. It was difficult to feel anything but empathy for these women, struggling with the same issues we struggle with today, doing the best with the limited information being doled out to them, constantly under the scrutiny of the male gaze.

And in Stratford’s Studio Theatre, not a single person could escape that gaze. Samantha McCue’s set design is filled with whimsy including an unending fire pit of kettles and tea cups, as well as zipline mail delivery, contrasted with ever-present powerful men from throughout history watching the audience and ensemble, their portraits hanging from the ceiling. Oscar Wilde in one of his most recognizable portraits, lounging as he looks down on the audience the entire night, threatening to choke us with his witty one-liners.

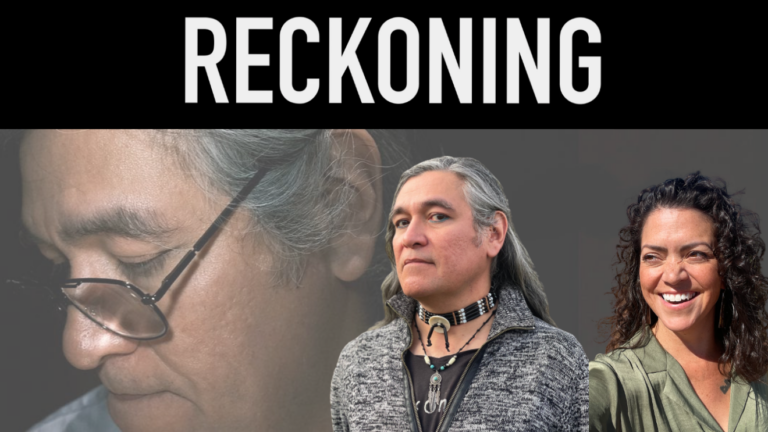

Though not entirely Indigenous, the production is a who’s who of some of the best Indigenous artists and creatives, all multi-talented and award-winning. Both Nolan and Barker are past artistic directors of Native Earth Performing Arts, with Peters presently at the helm. It’s an absolute delight to see such an incredible cast together, supported by equally accomplished creatives. It’s one of those rare productions where the entire ensemble fits together seamlessly, no one voice overshadowed by another. It’s so beautiful to watch and difficult to adequately credit without just regurgitating the program.

All that being said, there is one plot point I wish Konkan had more clearly developed. Why are these specific three women together? Eugenia is the go-between for her fur-selling Ojibwe family and the fur-purchasing settlers of Cecilia and her husband’s business associates. But why is Marie-Angelique there? She is angry with her mother, unsure if she was abandoned or taken away, feeling pain no matter the circumstances. Surely Cecilia would have some insight that she could share? Being in the trio and not with her mother is a point of friction for Marie-Angelique, but it is under-explained for its overall significance to the story itself. This left me scratching my head at times, feeling perhaps I had missed something.

Growing up, learning about Louis Riel: he was a petulant child with messianic delusions rebelling against the benevolent Hudson’s Bay Company and fair and just John A. MacDonald. Being taught these sorts of narratives, I felt shame (and some stickin’ it to the man, anti-authoritarian glee) when I first learned that my kind of “mixed” is Métis, and I’m certain I do not hold a monopoly on this experience. My feelings of shame are long gone, but our history is still missing dimensions outside of our communities. Though it’s changing, a lot of the formal documentation and texts children learn from are written from a colonial, male perspective where women are, at best, downplayed, and at worst omitted completely. Historical fiction is a powerful tool to expand our understanding of ourselves, and Koncan wields it with precision and care.

Women of the Fur Trade is a gift. Koncan carves space for us to laugh, question, and imagine where us women fit in the times of resistance in Treaty One, on the banks of the Reddish River.

Women of the Fur Trade plays at the Studio Theatre in Stratford through July 30. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

L o s i n g $111,555 overnight was a crushing blow. The account lockout and subpar customer service that followed left me stunned. However, I gained invaluable insights from this ordeal : Conduct thorough research before committing Verify credentials and read reviews from multiple sources Be c a u t i o u s of un realistic promises Demand responsive and reliable support. Fortunately, I found chelsy__desmarais__54__A T__g=m=a=i=l__D=o=t__c_o_m, which helped me re-cover from this financial setback.

W_h_a_t_s_A_p_p ; +1=8=5=9=4=3=6=4=2=1=1

I recently fell victim to this devastating scam company that involves me into investing 97,000dollars in bitcoin which surprisingly grew to 262,000dollars within weeks. However my excitement was short-lived as i soon discovered it was a fraudulent scheme that i could not withdraw my funds, then i got into an online search and found Bruce Nora who has been helping a lot of people in recovering back there lost fund, and then i got in contact with her and she helped me in recovering back all my money in total, all thanks to Mrs Nora for helping me to recover back my lost funds, if you were involved in any fraudulent scam get in contact with; b r u c e n o r a 2 5 4 [AT] gmail.com