Spotlight: Mike Ross

The first time I became aware of Mike Ross was some dozen years ago in a Soulpepper production of As You Like It, directed by Albert Schultz. The cast included a few of the company’s reliable regulars, but most were younger, including several from the initial intake at the Soulpepper Academy. Ross was one of them. He played the traditionally unrewarding role of Oliver, the hero’s bad older brother, and I was amazed by how much, without any obvious strain, he was able to make of it.

When I mentioned this to him, during a conversation in the Soulpepper library, he told me that before that production, he “had been in denial about being an actor.” He also reminded me that Oliver hadn’t been his only contribution to that show; he had composed the music for the play’s many songs (I did just about remember that) and he had played Amiens, the banished lord who gets to sing most of them (I hadn’t remembered that, though in light of later developments I certainly should have). It’s a fairly safe assumption that, in the long stage history of As You Like It, Ross is the only actor ever to have doubled as Oliver and Amiens. But it suits; he’s both actor and musician, and excellent at both. The music though, came first, chronologically, and it’s continued to be his personal priority. For the last five years, he’s been Soulpepper’s Slaight Family Director of Music, a position created especially for him; and the company is about to open its first full-scale original musical: Rose, based on a story by Gertrude Stein, with Ross as its composer, musical director, co-librettist and prime mover.

When Ross first joined the Academy, he was “pretty forthright about not wanting to be an actor.” So says Sarah Wilson, who was Rosalind in that As You Like It, his contemporary in the Academy and a friend ever since. (“We see each other all the time. Our kids hang out.”) They are also co-workers; she wrote the lyrics for Rose and they collaborated on the book. They started writing together, says Wilson “about four years ago, and after a couple of false starts we really got going.” Among the ideas they batted around was a musical based on Rapunzel (shades of Into the Woods). Then Wilson discovered the Stein collection The World Is Round with “beautiful pink pages. It had been reissued years before. There was a musicality to it. They sing all over the place – though there are no songs that we’ve actually used.” And from it came Rose, the story, as Ross describes it, of a girl who’s “just turning ten and going through an existential crisis, not knowing who, where or why she is–while other people try to tell her. Sarah originally approached me with the idea of making it a chamber-music piece. But as we started working on it, it became clear that there was a bigger story, something quite macro in this micro.” Or, as Wilson puts it, “I thought it would be some weird little musical to do in cabaret. But Mike’s the opposite. He’s ‘let’s go bigger’.” Ross: “It became an epic idea for us, inspired by Gertrude Stein’s quirkiness. We’ve set it in a mountain town.” And in the score, “theatre music meets mountain music.” And though he counts Rose as “my first musical”, it sounds in that respect like a logical successor to Soulpepper’s memorable Spoon River, for which he composed a score in which theatre music met all kinds of American folk music.

Ross himself has a good bit of America in his background. He was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, but raised in New Jersey; he played trumpet there in his high-school marching band. He attended university in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, but got his degree back in PEI. He was planning to be just a musician (“I wanted to score films”) and “got into acting because of music.” The re-routing occurred when the Charlottetown Festival mounted a production of Fire, the bio-musical about Jerry Lee Lewis; he played the lead. And having “got the bug” (it may have already been partially implanted back at Wilkes university, where he had played the Soldier in Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale) he moved to Toronto. And then came the Academy, whose purposes and achievements included having theatre artists from different backgrounds and disciplines rub off on one another.

He was, by his own admission, “very green as an actor.” Wilson remembers the greenness but she qualifies it: “he was very green and open.” (She also remembers him being “kind of stiff” which, in light of later developments, is surprising.) His first appearance with Soulpepper’s main company was definitely in a musical; he was Money Matt, one of Macheath’s gang, in The Threepenny Opera. He corrected my impression that he had been at Soulpepper pretty much continuously ever since: “After leaving the academy, it was 14 months before I worked here again”. His most memorable appearance outside was as one of the shambolic assassins in Adam Brazier’s superb production of the Sondheim musical of that name, which enabled to him to act, sing and—given the actors-as-musicians concept—instrumentalize. Back at Soulpepper he was the hapless Baron Tusenbach in Three Sisters, the neurotic playwright forcibly turned actor in Jitters (an especially juicy and funny performance) and Happy in Death of a Salesman. He was also a delightfully self-centred Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his second achievement in rescuing a usually thankless Shakespearean role; indeed he and Brendan Wall, playing Demetrius, brought off the unheard-of feat of making the play’s male lovers more entertaining than the females. Ross himself says that, though he doesn’t want to act any more, “Shakespeare might get me back”.

His success in Shakespeare may owe something to a musician’s sense of rhythm. Wilson has an additional take on it, “He doesn’t care about the rules. He resists doing things because ‘that’s the way we do it’. He seems like a real human being.” She also says that “he’s the least neurotic artist; not cocksure or arrogant. He’s just a sensible dude. And he’s a busy guy. People are always wanting him to do things. He’s very generous.”

Hailey Gillis speaks of Ross in the same terms. She’s playing Rose’s title character whom she describes as being “very sure about how unsure she is. She feels the injustice of living in a world where no-one asks questions. She can’t articulate herself. Music gives her clarity in her nine-year old brain.” Gillis’ relationship with Ross goes back five years; she was in the Academy and he had become Soulpepper’s Director of Music. The biggest thing she had done with him before was Spoon River, a show in which she spent most of her time immured in a coffin. When she awoke, she sang. “He’s very collaborative. He lets me explain what my idea is. He’d say ‘do that Hailey Gillis thing you do’ and he trusted what that was. Many musical directors want a specific sound from you; he’s interested in your unique sound. If you look at his music, it’s not easy, but it’s very accessible; he has an amazing quality of writing songs in character. He reads something—and he’ll hear it. He’s very sensitive to people. He has a certain level of expectation, and you rise to the occasion. He’s so funny, but he runs a really focused rehearsal room.” And Wilson confirms that “Mike is an amazing leader in the room; looking at him, he’s always in motion.”

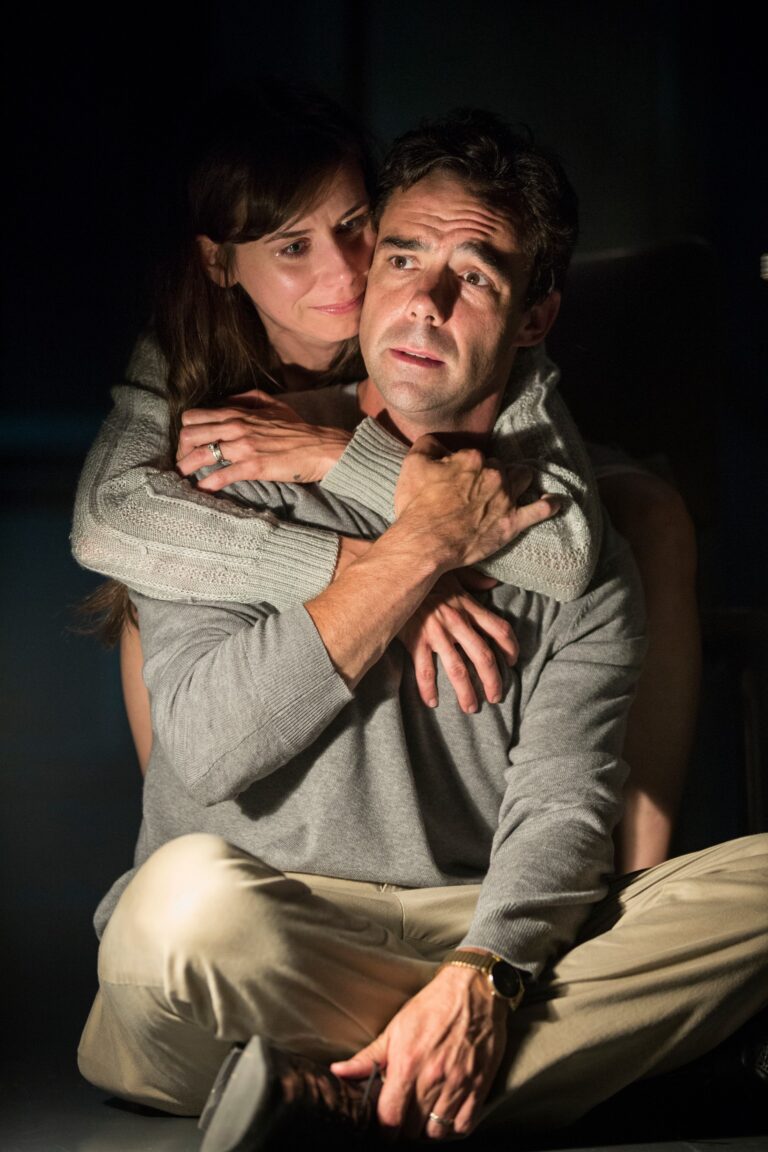

Mike Ross, Frank Cox-O’Connell, Raha Javanfar, and ensemble in rehearsal for Rose

Weyni Mengesha, Soulpepper’s incoming Artistic Director, would agree. She said in an email that “both as an actor and a musician Mike brings an incredible amount of heart and imagination to his work. He is a dreamer, and his excitement around creative possibilities is infectious.” Mengesha was another member of that first Soulpepper Academy (it was a rich vintage) and according to her “it was clear from the beginning that Mike was a huge talent. I was able to direct him when he played the lead in a show we did in the Academy and it was amazing to see his process. Whether I am watching him perform or listening to his music I always find myself moved. We are so lucky to have someone with such musical ability who is passionate and clear about story. I am personally really looking forward to collaborating with him and to share some of the new ideas he has been cooking up.”

She also said “I think Mike has created a unique musical experience with the Soulpepper Concerts, and the audience reception has been incredible.” Those concerts have been a vital part of Ross’ contribution as Director of Music, a post without precedent which he describes as “pioneering ground – it’s hard to make a job description of it”. The concerts grew out of Soulpepper’s now discontinued Cabaret Festival. (I have personal fond memories of performing alongside Mike in one of those cabaret shows, a Sondheim Songbook. He was very encouraging.) The concerts all have connecting narrative threads; Berlin to Broadway was the first one; another, of which he speaks with especial pride, concerned the alarming number of musicians who have died at the age of 27; the title was The 27 Club. It was, he says, a case of “information meets interpretation. It wasn’t just an excuse to sing their songs. They didn’t necessarily break bad because of their lifestyle; they were trapped. We asked, who created that trap? We’re a theatre company, so what we do has to be filtered through story, words, context. We have a unique aesthetic identity. One side of it is music filtered through a theatrical sensibility. We’re dealing with music theatre, not musical theatre. My tastes are more rough around the edges – I come from the rock ‘n’ roll side of things.”

[display_gallery]Somewhere on that music-theatre spectrum, between the concerts and the musical, Mike Ross has become the go-to guy for furnishing not-so-incidental music for plays: for Under Milk Wood, for example, where the music “came in useful as filler” and for Of Human Bondage where the music was as vital part of the production as the visuals and where the experience must have come near to realizing his original dream of composing for the movies. He was “inserting stuff within days” of the opening, and he “had to be brazen enough” to see it through. “When you’ve been in the academy, you feel you’re one of the little guys; I had to assert myself.”

With Rose, says Wilson, “we wanted something you can bring your kids to, but you don’t have to.” Ross says the same thing in slightly different words: “It’s a kid’s show for grown-ups.” He also says that, for him and for the company “It’s got to be words first, ’what’s being said here?’ Setting other people’s words to music is what I’ve always done, and this is the apex of that”

Comments