In A a | a B : B E N D, choreographer Aszure Barton aims to rebuild dance from the inside out

“We’re all rooted in our patterns — bubbles floating through the universe on our own — and I realized I needed to bust the bubble and explore a bit to intentionally expand,” Aszure Barton, the Canadian-American choreographer, tells me over a video call focused on A a | a B : B E N D, the cryptically titled dance-concert hybrid, which lands at the Bluma Appel Theatre for three nights starting December 4.

At the beginning of 2020, Barton was holed up inside, reflecting on her two decades of work — but beneath that warmth was a sharp restlessness. “I was looking inward and investigating where I was at in my career, and I knew I could go deeper and challenge myself,” Barton said.

She phoned an old musician friend in Toronto to see if he knew of any new music that might light her fire. “Without hesitation he said ‘Ambrose Akinmusire,’” the American jazz composer known for his unguarded approach to improvisation, Barton recalled. “I hung up, listened to one of his albums and then collapsed. I didn’t anticipate how much it could open me. I was able to cry in a way I hadn’t and the music became a portal to possibility.”

When Barton has a profound impulse, she tells me, she’s unstoppable. Immediately she reached out to Akinmusire, and it turned out the desire to work together was mutual — Akinmusire had been a quiet fan of hers for years. “There was this kind of mutual adoration, and when we got started on the process we found a rhythm of creative trust that was built on curiosity,” said Barton. “From my side, it felt like I was being lifted up.”

The hour-long B E N D is billed as a dance performance, but Barton says that while it includes dance, the genre is more accurately a collaborative hybrid. On the first day of in-person work with dancers from her company, Aszure Barton & Artists, she offered no counts, no framework. “I simply asked, ‘where do we begin?’” she recalled.

“There’s a historical hierarchy where the choreographer says, ‘this is what I want; these are the steps.’ But that was not this relationship.” The dancers, many of whom have worked with Barton for over 15 years, began by improvising. Then, Barton turned to longtime collaborator Jonathan Alsberry and asked him to create a rhythm by watching the dancers’ feet. He recorded himself performing their rhythm, sent it to Akinmusire, and it became the seed for B E N D’s music.

The process was a constant exchange between Barton, Akinmusire, and the dancers. Barton’s goal was for her and her dancers to “unlearn” the physical conventions they were comfortable in to make way for a raw connection to the music and each other. Because so much of the choreography came from gut and intuition, Barton filmed constantly; from this footage, she and the dancers would then relearn and incorporate the most beautiful moments.

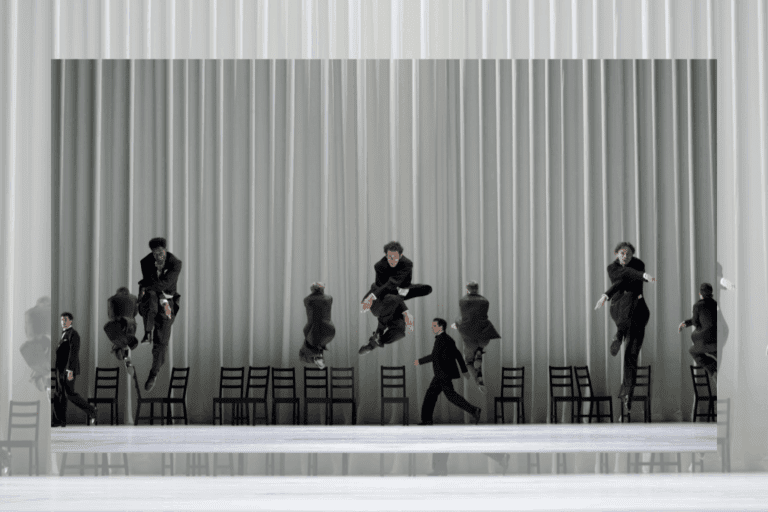

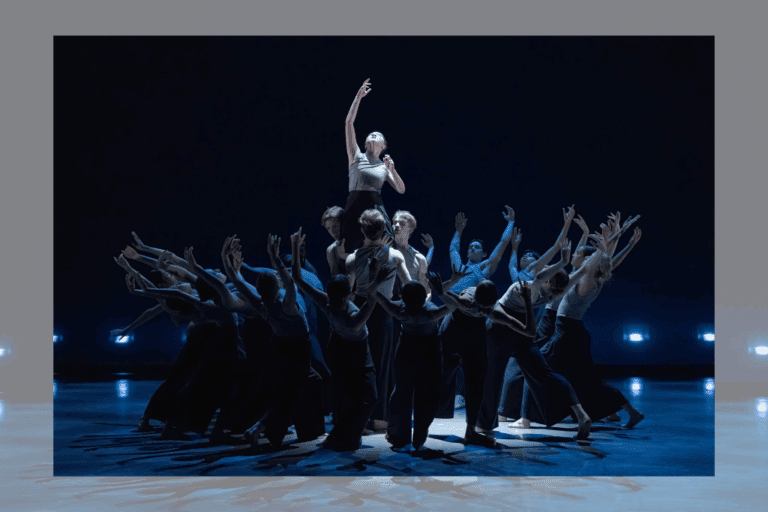

The resulting production resists definition. On a dark stage, the cast of 11 dancers, who range in age from 23 to 48 years old, wear matching black joggers and fleece hoodies. From what I can see in the trailer material, they pop and freeze, swim and curl, or dissolve into everyday gestures. Akinmusire shares the stage with them — more conductor to the dancers than accompanist. He might smile at them or add a surprise, responding to their energies while playing recorded tracks, live trumpet and keys, manipulated synths, and improvised jazz.

One could see certain traces of breaking and modern dance in the choreography, but TO Live’s website description of it as “authentic movement” seems most apt. Earlier in Barton’s career, critics labelled her work as emotionally rich contemporary dance, but her more recent works, B E N D being key among them, run on visceral impulse and a co-authored fusion of sound and movement that forms not a collage of genres, but a sonic-somatic ecosystem.

“It’s so easy to over-intellectualize dance in general, but B E N D is about hearing and moving to cool-ass music together,” said Barton. “There is structured choreography that works like a shared language, but within that there are windows for the dancers to improvise and to fall in or out of the piece. The goal, sometimes, is for the dancers and Ambrose to challenge each other to get lost before getting back on track.”

Eventually I asked Barton about the work’s title. It’s got a quirky arrangement of capitals, bars, spaces, and a final insistent word that evokes action or shape. To me, A a | a B : B E N D feels like a doorway that opens all the themes of the show. It’s not obvious how to pronounce it; saying it aloud becomes a tiny act of vocal improvisation for the sayer, the lips, tongue, and teeth forming their own orchestra. The opening letters, A a | a B (Barton and Akinmusire’s initials) look like a groovy musical score and seem like a play on “A/B-ing,” music mixing slang for comparing two different mixes. And the spaced out letters seem to suggest a kinetic clearing.

Barton confirmed that this kerning points toward a kind of openness. “So much of what we do is random. The title unfolded really organically. Ambrose at one point said something about how far we can bend before we break, and we had a working title that was ‘beginning, middle, bend.’ We shortened it to ‘bend’ and added the spaces. Space is often seen as distance, but I think space is structure. As collaborators we built space for each other to grow in.”

In our last moment of the call, I asked her what she hopes audiences will carry with them after the curtain falls. “I hope that people allow themselves to feel what they feel — but hopefully that feeling is fantastic! There’s so many layers for the audience to capture in their own bodies,” she replied. “And the show is dee-licious. I hope all sorts of people, but especially young people in their teens and 20s, come, feel all of its layers and vibrant energy, and leave fully satiated.”

A a | a B : B E N D runs at the Bluma Appel Theatre until December 4. Tickets are available here.

TO Live is an Intermission partner. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments