In Conversation: Yvette Nolan

Yvette Nolan believes we live in a world full of fear: fear of working cross-culturally, fear of making the wrong decisions, fear of having difficult conversations. The Algonquin/Irish playwright, director, author, and former artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts explores this fear culture and what it does to the art.

One is not enough

We still have that idea that one is enough: one Tomson Highway, one Ian Ross, one Kevin Loring. That goes in any community: if we have one differently-abled writer, if we have one Asian writer, if we have one Black writer, it’s like there’s only room for one. We don’t have critical mass. We don’t have a theatrical scene in Canada that actually looks like Canada, yet. Everyone’s working to make that happen, I think. And there’s been a lot more push to include Indigenous voices and Indigenous stories, but what that creates is also the idea that people are trying to appropriate our stories… again. And it’s neo-colonialism, a new way of doing that. And I think that makes producers and potential partners afraid of reaching out, and I think it makes Indigenous artists or artists of colour afraid to tell a different kind of story. I think everyone is afraid.

Making art in a world that runs on fear

Sherman Alexie, the Coeur d’Alene writer, says that Indigenous artists don’t have the luxury of just making art: we’ve been silenced too long, we’ve got too many stories, we’re responsible to a community. All of which I think is true. But in the fear culture, [people] maybe feel like [they] should just make art that is not [political]… But it’s impossible. In the world in which we live, we actually have to make work that is vital, that is critical to the conversation. Maybe [that] will just cull out the people who are dabblers and dilettantes, and only the people who are actually driven to speak in this form will do it. It’s running the gauntlet.

Theatre reviewers as gatekeepers

Theatre reviewers, who are mostly white, male, and of a certain age, who have come from a certain school of what theatre is, are reviewing accordingly. And what they do is they end up gatekeeping. They end up telling the reader about the way they receive the theatre, and if it’s not theirs, if it’s something they don’t understand, they write accordingly.

This is a challenge in Indigenous theatre and other kinds of theatre and storytelling. The reviewer comes in and goes—and we just got a review like this for Bearing at Luminato—“I came in expecting this. That’s not what I got. And therefore it’s a failure.” That is essentially what the review is. How about if you come to see the show, you see the show that you’re being offered, and you respond to that, instead of responding to what you’re not seeing.

The fear of community backlash

Indigenous artists or artists of colour—artists who are not the powers that be—are also afraid because there’s a backlash from within our communities. You can’t make everyone happy. So if I choose to partner with a theatre that is not an Indigenous theatre—which of course I have to, because there’s really only five Indigenous theatres in this country—if I choose to partner with a mainstream company in order to move this conversation forward, in order to be in the room and have this discussion, then that’s what I choose and I do that out of my values and my teachings. But there are still people from within my so-called community who are going to yell at me for being a cultural informant, for playing with whitey. But it doesn’t matter. You cannot win.

Kevin Loring, the new AD of the new Indigenous Theatre section at the NAC… He’s going into a big white institution. And we’re all hopeful. But we’re also all afraid. Because that structure has existed for a long time without any Indigenous worldview inside of it. And so any number of things can go wrong.

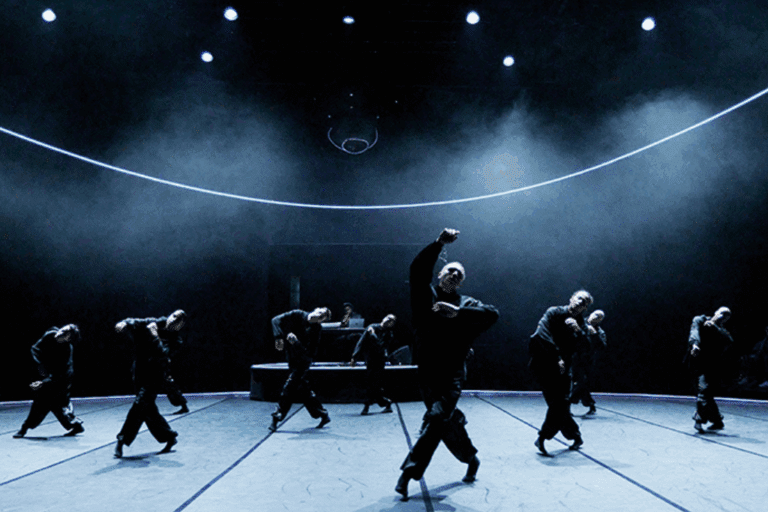

Yvette Nolan directing. Photo by Gayle Ye

On tokenization

You can’t be responsible for the intentions on the other side. I can’t be responsible for whatever is going on in that person’s heart when they ask me to be a part of a project. I can only be responsible for my side of the equation. Which is: what is the work, why do they want to do it, how well do I know this person, what is my interest in the work, how is this going to move the conversation forward? And then make decisions accordingly. And then have to live with them.

The culture of instant reaction

It’s all happening on social media. It’s why I don’t do it. I’m not on Facebook, not on Twitter, because that to me is all anti-theatre. My form is theatre, and theatre is about being in the room. If you want to be in the room and have the discussions, then let’s do that. But let’s not just do it in 140 characters. It’s all posturing. Well, much of it is posturing. And it’s too easy. It’s too easy to just join the villagers with pitchforks on Facebook and be like, Yeah, yeah, I agree, without knowing anything. So let’s move beyond that and let’s do the work. And then let’s talk about the work after the work.

Leaning into the fear

My friend Shawna Dempsey, the performance artist, says, “You’re either scared or bored. And scared is better.” [As] individual artists, we have the ability to just make work and damn the consequences. It’s when we actually have to partner with people with power and money that it starts to get complicated. Because the people with power and money have facilities, they have funders, they have patrons, they have all kinds of reasons to be afraid. And that can put a damper on the work that you’re doing inside of that institution. I understand that. But, you know, that’s why we can’t make change.

My own fears

I’m usually afraid at the beginning of everything. I had a meeting with Maria Campbell [recently] and we started creating a play at lunch, and at one point I was like, “Wow, we are going to be in such shit.” Really scary. And then I was like, Okay, that’s a good sign. Like, if it’s that scary then it must matter. And therefore am I willing to throw in on that? Yes I am, let’s go.

A little bit of fear is good, because it means you have to do due diligence about the work that you’re going to do. You have to know why you’re doing it. And then you have to be ready for the slings and arrows. Because they’re gonna come. If you’re making theatre that shakes the world at all, they’re gonna come.

Comments