REVIEW: Little Women at Stratford Festival

Stratford’s not-so-little take on one of Western literature’s most beloved families is at times lovely, usually charming, and consistently long.

That longness is double-edged — more time to spend with director Esther Jun’s loveable and well-calibrated cast is far from a bad thing. And in three hours, Jordi Mand’s adaptation of Little Women covers an astonishing number of Louisa May Alcott’s plot lines, sparing little. Fans of any number of Little Women adaptations — the 1999 musical or 2019 film treatment, in particular — will feel right at home in Jun’s take on Civil War-era Concord.

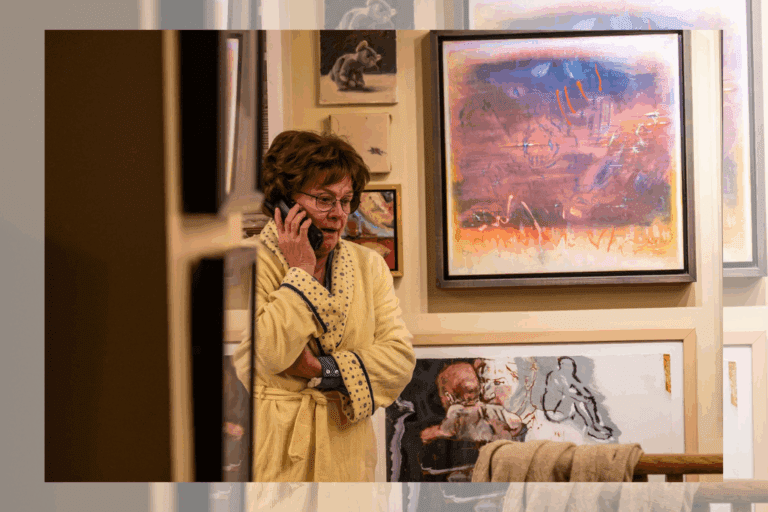

But there’s no denying that this Little Women is a beast, with fat to be trimmed and heart to be further coaxed out. Led by writer Jo (a confident and compelling Allison Edwards-Crewe), we dive into her life story through a trapdoor in the Avon Theatre stage, masked cleverly by a bottomless steam trunk. Soon enough we meet the whole March family, who boisterously climb out of the trunk: sweet pianist Beth (an engaging Brefny Caribou), petulant Amy (a funny Rose Tuong at the performance I attended), and sensible Meg (a standout Verónica Hortigüela). At the helm of the March family are mother Marmee (the spellbinding Irene Poole) and obstinate Aunt March (the oft-menacing Marion Adler). Allies to the March family include elderly neighbour James Laurence (John Koensgen), his grandson Teddy (Richard Lam), and Teddy’s tutor John (Stephen Jackman-Torkoff).

Connections emerge quickly between the March and Laurence clans: there’s a clear fondness between Jo and Teddy, which becomes increasingly one-sided as the two grow older, and Meg and John seem to have a certain chemistry, too. Beth takes quickly to Mr. Laurence’s out-of-use piano, and Amy finds herself a foothold in the Laurence family while studying art in Paris.

Mand truly has preserved every wisp of Alcott’s novel, including the curling iron incident, the skating accident, the book-burning, the story-selling, the lime-trading, and more. But the production here almost seems overstuffed, combining hefty plot with anachronistic visual choices: the 1990s and Civil War eras converge in Jun’s production, sometimes talking over each other instead of entering into a followable dialogue. The era-mixing can make for some fun juxtapositions — Teddy and Jo first dance together to Björk’s “It’s Oh So Quiet,” and Beth plays ostentatious Radiohead refrains on her piano during scene changeovers. But the “why” of these choices occasionally gets lost in a story so sprawling, and the March sisters, seemingly ripe for modernization as feminist literary icons, still feel rooted in Victorian Massachussetts, partnered off, child-rearing, and fearing spinsterhood. Jo’s discomfort in her own skin and Marmee’s total selflessness for those less fortunate offer narrative threads largely left unpursued, kept simple in the interest of piling on more story. Existential questions about womanhood and class mobility are asked loudly and compellingly — but I don’t know if we’re consistently offered answers by this production and its time-travelling costumes and songs.

None of this is to say Stratford’s Little Women isn’t enjoyable — Alcott’s stories are the perfect blend of relatable and aspirational, anchored by strong performances from a diverse and endlessly watchable cast. Healthily-budgeted stagecraft makes a number of delightful appearances — Teresa Przybylski’s modular set feels like a life-size dollhouse, and Meg’s wedding drowns in soft pink flower petals. Kaileigh Krysztofiak’s lighting, too, is consistently flattering to the production’s set and ever-evolving costumes (by A.W. Nadine Grant).

If you’re a die-hard Little Women fan, this’ll likely tick your boxes, and if you’re not, the production’s not an unpleasant way to spend an afternoon at the Stratford Festival. But I can’t help but wish this Little Women were written as if by Jo herself, fearlessly and without hesitation — this one is safe and squeaky-clean, a likely family hit without much bite.

Little Women runs at the Stratford Festival through October 29. Tickets are available here.

Comments