Binge-Worthy Theatre

Some thoughts on writing collaboratively, written collaboratively by the showrunners of the theatre miniseries The Numbers Game.

JAMES

Well, Emma, here we are.

EMMA

Hey babe.

JAMES

Sitting in the same room, pretending that we’re not.

EMMA

It’s Pinter-esque.

JAMES

How should we start?

EMMA

I think where our little miniseries, The Numbers Game, started—at that bar a couple years ago, after a play reading that left us kind of cold. We were talking about the common traits, themes, and styles that we found overused or uninspiring… The usual nitpicking that comes with seeing a lot of new work.

JAMES

Yeah. We’ve both thought for a while that theatre feels strangely strangled by a bunch of made-up limitations. It’s the most versatile medium, and yet it has this unfortunate reputation for being same-y… I would say it doesn’t deserve that reputation, but that seems to be the way non-theatre people see it.

EMMA

Or at least a little bit stuck…

JAMES

Kitchen-sink dramas, Shakespeare, and Andrew Lloyd Webber.

EMMA

… I mean…

JAMES

It’s important to stress that there’s nothing wrong with kitchen-sink dramas, Shakespeare, or Sir Andrew.

EMMA

Thank you.

JAMES

I’ll always avoid generalizations for you in the public eye, hon.

EMMA

Aw snookums. I think the scope of theatre in Toronto, in Canada, and internationally is considerably greater than we give it credit for when we’re in our cups, tipsy, and bitching about “all the problems with art these days.” But it’s also when you’re at that place (cups, tipsy, bitching, etc.) that you can get to the heart of what you wish you’d seen.

Ngabo Nabea and Dwain Murphy. Photo by John Gundy.

JAMES

I always think about an introduction to a book of genre stories (a McSweeney’s, maybe?) that I read once, where the writer basically said, “Imagine if after Farewell to Arms every novel was about the romance between a recovering soldier and his nurse.” The writer was talking about the heavy use of “revelations” in short stories, but I think the idea applies here too. There’s nothing wrong with the realistic, grounded, character-driven Canadian stories that have dominated Toronto stages for so long. But when the medium allows you to set those stories on, say, a crashing spaceship, why not take advantage of that? And the thing we kept circling back to after that reading was: Why are there no mob plays?

EMMA

Well… I think at the time I was binging my way through Boardwalk Empire. And you and I have always shared a fascination with the world and history of organized crime. Maybe we’d just seen one too many kitchen-sink/family dramas, so we were overwhelmed by storytelling that underwhelmed. And I really wanted to see how you could put something like Boardwalk on stage.

JAMES

It seems like everything that makes a mob movie great would work even better on stage. The secret sauce of the mob genre is tension, not violence. And tension is something theatre can do better than any other medium, I think.

EMMA

There’s that. And also that the storytelling I find the most compelling is, generally, found in television shows. Often it’s not even the stories, it’s the way they’re told. I want the cliffhanger. I want to need to see the next episode.

Karine Ricard. Photo by John Gundy.

JAMES

That comes from two things, I think. First of all, the exhaustive discussion in film and TV about story structure, which as a screenwriter can be really annoying, especially when you’re starting out. But when you drink the “Structure Kool-Aid” the whole world opens up. Second of all, the fact that TV in particular is a medium driven by writers, plural, not one writer, singular. That a group of talented people are thrown together in a room, get their hands all messy in each other’s scripts, gripe about their showrunner being a total dick, and then end up with something they can take credit for collectively. I’ve never been an actor, but you have. So maybe you can tell me: is the closest analogy here the theatre rehearsal process for actors?

EMMA

That seems accurate. In rehearsal a group of people mine for the story, sink into characters, figure out how to tell that story to an audience. This often isn’t the experience for playwrights. A huge driver for us in this project was the word “structure,” something we both felt was lacking in much of the playwriting we saw. Which makes sense. There isn’t much in the way of post-secondary training for playwrights. There’s really no cut-and-dry way to learn your writing process, find your voice or aesthetic, or become a playwright aside from doing it. Writing plays, making mistakes… figuring out what works.

JAMES

Although I think that’s also the medium. Screenwriting books will tell you not to stay in the same location for longer than two or three pages. That’s a little harder on the stage.

EMMA

Right, but that’s setting… not structure necessarily.

JAMES

True, but structure comes from scenes and scenes come from setting.

EMMA

…

JAMES

This is where you call me a dick.

Jeanie Calleja and Emma Mackenzie Hillier. Photo by John Gundy.

EMMA

Mm-hmm… Someone like David French, Canada’s grandfather of the kitchen-sink drama, knew how to structure a whole story in the kitchen (surprise) of a family in Toronto. So, you dick, the setting of that show wasn’t as much about setting as structure. But it shouldn’t come as a surprise that David was writing radio plays before he turned to theatre. His plays adhere to a certain structural storytelling. Something we might refer to as “the well-made play.”

I don’t know about you, but for me this project was also fascinating because as a dramaturg my job is to support, not to lead. As a screenwriter, you have to fulfill the wishes of others in your script. For me, this project was about leading a process to tell a story theatrically in a new way. A story that can’t be told in a single night and requires a big group of people working together to fine-tune it, discover it, create the world with us, and mine for plot points or intricacies that we can’t see on our own.

JAMES

Totally. Theatre’s so collaborative, but it sometimes seems to me (as an outsider coming from film) that the writer is sort of separate from the rest of the team.

EMMA

That’s a fair point. But, truthfully, there is a great deal of control in the hands of the playwrights, until there isn’t. And there is great respect for the written word until there isn’t. Bob White once said to me that he wished actors would treat Shakespeare with less reverence and new work with more. There isn’t much in the way of continuous input for playwrights, even when working with a dramaturg. The playwright sets the pace for that relationship so if they want a lot of input, they get it… if they don’t, then they don’t. Which is where The Numbers Game is completely different. We wanted to try a whole new style of development in order to produce a completely different kind of show.

James McDougall. Photo by John Gundy.

JAMES

In TV, the writer and the showrunner make a pact. The showrunner says “I’ll give you weird people this idea I’ve been working on for years and ask you to bring it to life. The script you write will be passed around the room like a hash pipe, and I’ll do a last pass on it that will make you hate me. But in the end, when the credits are on screen, they’ll say that we all made this together—and it will be true.” As far as I know, nobody has ever tried that with a roomful of playwrights. And that was what excited us the most.

EMMA

And hopefully that’s what excited our playwrights as well. I think one of the scariest parts of a project is giving up your voice to another artist, whether it’s for notes or edits or whatever. But we’re very lucky to have found the playwrights we did. Claire Burns, Meghan Swaby, Bahia Watson, and Beau Dixon were brilliant. They committed themselves to an entirely new process with gusto and communicated when the process was working for them and when it wasn’t.

JAMES

And giving up your voice goes both ways, right? We could write our bible, our little outline, but in the end it was down to them.

EMMA

Absolutely.

JAMES

Like Eisenhower’s letter to the troops on D-Day. “Welp, good luck out there, champ, try your hardest.”

EMMA

How many history jokes are you going to make before we’re done?

JAMES

I’m done.

EMMA

Uh-huh.

Cal Shillingford and Jeanie Calleja. Photo by John Gundy.

JAMES

What else did you find challenging?

EMMA

Well… We knew we had to create a room where everyone’s voice was equal—especially considering we’re white and it’s set in 1930s Harlem. We had to create a safe space that welcomed and encouraged discussion about the story’s racial themes. We had so many conversations in the writers’ room about how those themes should impact the structure, how and when to use slurs that were common at the time, and even how to protect the actors and the audience through the text so they’re not pulled out of the story.

JAMES

Personally I have a lot of anxiety about the reaction on social media. Even the suggestion of improper behaviour, accurate or not, can be really devastating.

EMMA

Yeah… it’s a bit tricky to talk about without being anxious about the reaction. But I think that’s the point. It’s scary to create a story that deals with race. I hope that by approaching the topic responsibly and respectfully, requesting input, bringing together a strong team from different cultures and experiences, and always listening to our collaborators for what they were saying or not saying, we created a healthy working environment.

JAMES

The process itself was a big part of that, don’t you think? By working through the story together, step-by-step, we were able to find a lot of connections between the present and the past that we might have overlooked otherwise.

EMMA

Totally. My only regret is that we didn’t have more time.

JAMES

I agree. Those long days breaking the story with the writers were the best part of my summer, and I wish we’d had more of them. But there was probably no way around that, short of starting way earlier, which next time we definitely will.

EMMA

Next time? Hehehehe.

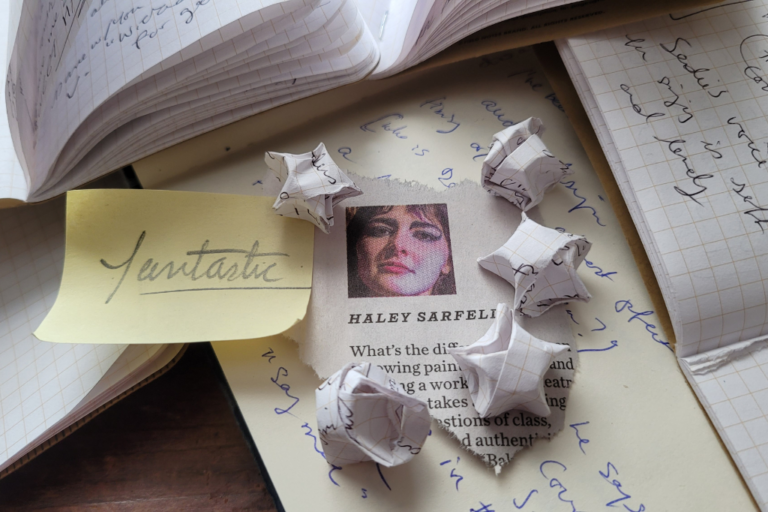

Emma in rehearsal. Photo by John Gundy.

JAMES

One of the selling points of this thing was “theatre for the Netflix generation”—or, in CanCon lingo, “theatre for the Shomi homies.” (R.I.P.) How realistic do you think that is? We figured out early on we couldn’t ask our actors to remember six hours of material in a couple of weeks, and then perform each hour on demand. So maybe HBO is a closer mirror? The “stay up late for Game of Thrones and tweet about it” model?

EMMA

We call the show “binge-worthy,” which isn’t completely accurate—the most you can binge is two episodes in one night. When I binge I’m usually watching five episodes in one go… God I’m addicted. The physical limitations of the human body, both actor and audience member, don’t allow for that in theatre. Which is where we got the idea for episodes over a number of weeks; the way I consumed The Simpsons every Sunday night at 8:00 as a kid, or the way we now wait with bated breath for the next Game of Thrones episode.

JAMES

Technically “binge-worthy” is still accurate. But maybe not “binge-capable.”

EMMA

Uh huh. You’re clever with words.

JAMES

*bows*

Karine Ricard and Beau Dixon. Photo by John Gundy.

EMMA

And the way channels now play the previous week’s episode before a heavily anticipated show for anyone who needs to get caught up… You can watch episodes 1 and 2 in the same night, or 2 and 3, etc.

JAMES

And you can’t torrent The Numbers Game, so we’ve got that working in our favour. Hopefully whenever people tune in they’re hooked by the characters, the atmosphere, the stylish dialogue, the rhythm of the story, and everything else the team has worked so hard on.

EMMA

Absolutely. Well, then. Are we missing anything?

JAMES

I think that about covers it for now.

EMMA

Our desire for theatre that inspires… because we were tired of the old familiar tropes.

JAMES

There’s definitely a few things we should cut from this piece.

EMMA

But not that last part. That last part is gold. And will probably get me yelled at by someone.

JAMES

I’ll take a quick run at it, you do a pass, I’ll do a final polish, and we’ll send it in?

EMMA

Yeah! I like that I get the last pass. I’ll make you sound way smarter.

JAMES

God, you’re such a dick.

Note: This article was rewritten extensively by the writers. Especially Emma. No, James. No, Emma.

The Numbers Game is on at Storefront Theatre until November 6.

Click here for tickets or more information

Comments