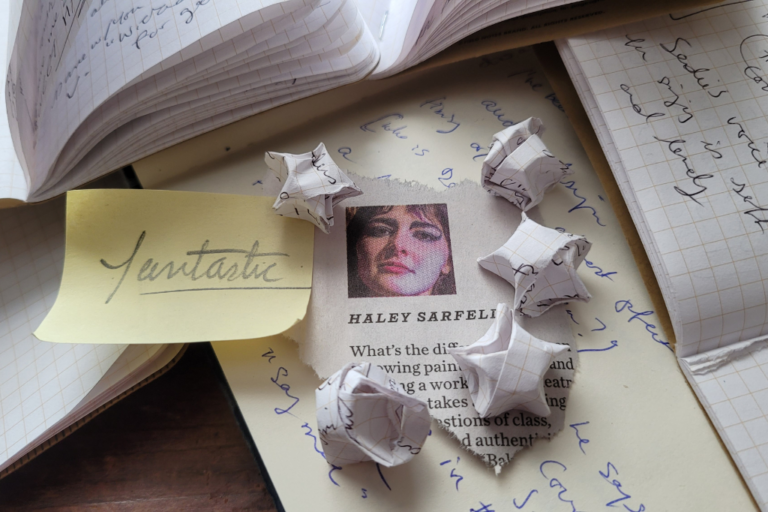

A Case for Arts Education

Why Me? Why This?

I’ve spent years teaching in various capacities through the GTA: as a substitute teacher, as a guest artist, and as an instructor for teachers on Professional Development days. I love working in schools, and I’ve spent a lot of time in schools, so it’s no surprise that my work as a writer and director is influenced by that environment. However, my interest in arts education runs much deeper. I tried to write about working with students and the way that I engage learners. But it turns out that I really want to talk about the importance of arts education, and the role of the professional arts in the sector, because I believe we can all do better at creating authentic opportunities for learners, ones that are part of our artistic process, rather than an afterthought.

A Good Approach

Given my background, I am regularly contacted by artists who are looking to “engage” students in their work/program or who are hoping to “connect” with teachers in advance of their upcoming show. Just as often, I am contacted by teachers about what shows are “good” right now. This makes me smile. These artists and educators have thought about building meaningful connections between learners and artistic work. While the impulse is so clearly good, these communications can also confirm the scary state of arts education in our city/province/country.

• “Engage” mostly means “find students who will do our youth program.”

• “Connect” often means “sell student tickets to our shows.”

• “Good” regularly means “something my students will like that isn’t too expensive.”

And if this subtext is true, I’m not interested in “engaging,” “connecting,” or finding work that is “good.” Arts education has become a sideline in the new four-year high school model because students don’t “have time” for those courses amongst all of their “core” subjects. And if a student wanted to study more than one art form? Unless they are at an arts-designated school, it’s no longer possible within the structure of secondary schools in Ontario. That means that students can only access arts-based learning in one field at school and pursue private (paid) options for anything further. In other words, shrinking opportunities in the arts in a traditional school setting is the set-up for systemic oppression (based on economic status) in arts training and, eventually, in the field of the professional arts. It is the responsibility of the professional arts community and professional artists to authentically and realistically approach arts education as part of the work we do.

(I also want to note that there are great examples of incredible arts education programming throughout Toronto, Ontario, and Canada. Their work should not be discounted or under-recognized. Great arts education programming is that which is fully integrated into an organization’s work, rather than a sideline project or a component of the marketing plan.)

It’s Like Camp

Kids love camp. Sure, there are a few who get homesick, but in general they love it. Camp is engaging, camp involves other kids like them, camp is where kids can be free. Shared experiences (even ones that involve sitting quietly in a dark room together) are valuable in a similar way. They can level the playing field: Everyone has had the same experience so they’re able to talk about it, regardless of their socioeconomic status or prior experience. The shared experience of the theatre (or a concert, or a museum, or a gallery) ensures that each learner walks away with a unique perspective. And it often provokes questions that might be considered taboo without the instigation of a work of art. In other words, participating in an arts experience together fights division and discrimination, invites critical thinking within a group dynamic, and initiates sensitive or difficult conversations. I’m not suggesting that effective arts education will end discrimination and bullying, but it certainly can help to create a culture of empathy. Imagine if the work of our performing arts institutions could start those engines earlier and more often.

Young People Aren’t Stupid

One of the perils of well-meaning-but-under-resourced arts education programming is assuming the intelligence of young people as lower than that of the artists or organizations involved in the creation of the programming. And yet we are driven to create programming to adhere to our grant regulations or just because we believe that arts education is important. Too often, however, rather than working hard to build bridges to reach learners in new ways, we do one of two things:

1. talk down to students so that they immediately feel like they are attending a lecture instead of a play, OR

2. assume that they “won’t get it” and therefore we ignore their opinions and responses in favour of suggesting that they’re “too young” or “naive” or “millennials.”

A good rule of thumb when approaching young people is to think about how you would respond to your offer. It sounds simple, but there are countless youth programs that I would never participate in because they don’t sound like they want participants as much as they want grant money. Young people are wise. They have good instincts. And they can smell a fake from a mile away. Spend time creating a great program and you won’t have to work as hard to sell it.

Know Your Audience

Just because you wrote a show doesn’t mean it’s good for students. Just because your show features teenagers doesn’t mean it’s good for students. Just because students will “like” your show doesn’t mean it’s good for students. And not all learners are young people.

If you’ve never worked with young people, or haven’t in a long time, you probably don’t know what is good for them. As artists, we have a responsibility to connect with experts who spend time with young people regularly; we must consult with teachers, community leaders, daycare facilitators, and/or youth coordinators to find out what aspects of our shows are worth talking to students about. Are there clear curriculum connections? Is it playing at a convenient time for students? Is there a particular topic that students will want to know more about? In short, what about our shows make them great choices for students? We need to develop these ideas in consultations with people who know more about that than we do.

But we also need to be willing to accept defeat. Sometimes, no matter how much we want to hold student matinees, a show’s particular content, form, or style means it just won’t work. Some shows aren’t a great fit for student audiences, and if we share that work with students, then we’re only hurting their understanding of the performing arts. I’ve seen beautiful and moving theatre that would be terrible for student audiences, simply because it isn’t built for teenagers. Older characters, poetic text, non-traditional structures, and lengthy runtimes all have the potential to alienate audiences. Good, contextualizing arts education can often overcome those hurdles, but not always. However, the great news is that learners come in all ages. There are a large number of adult education and recreation programs that might include our perfect audience.

“Bad” Plays are Good Plays

Increasingly, we find ourselves surrounded only by the things that we like: our social media feeds are full of opinions similar to our own and of articles that we are already interested in. We are rarely confronted with information that isn’t to our taste. And yet we are equally obsessed with outrage and finding something wrong with anything that we don’t like. It’s created a polarity of opinions; we have become binary in our responses as we either like something or we don’t. There isn’t much of a grey area allowed. Yet in the performing arts we ask our audiences to live in that grey area, to ask questions, and to have critical and creative discourse.

The responsibility of arts education is to ensure that young people don’t fall into the trap of a polar response to an arts experience. Rather, we must provide vocabulary for discourse and allow opportunity for discussion that falls far beyond a “like” or “dislike” binary. If we teach students that a play is only valuable if they liked it, then we disable the opportunity for critical discourse, and shortchange ourselves as artists. In the same way that audiences can enjoy a sports event even if their team loses, arts education can provide the context required for learners to appreciate an artistic experience even if the art on stage wasn’t to their taste. Too often we ignore the possibility that something could be worthwhile even if we don’t like it. Good arts education programming encourages students to start to make that connection.

Student tickets are simply not enough (even if they’re cheap/accessible). Just because a student has seen a play doesn’t mean that they’ve had a positive arts education experience. The shaping of that experience is what makes it memorable, and what makes it a learning opportunity. So there’s no such thing as a “bad” play, provided it is presented with context.

Not Just the Audiences of Tomorrow

Arts education is so much more than securing the “audiences of tomorrow.” Arts-focused education is about relating to students who might not otherwise connect with standard curriculum. It’s about teaching students the value of their own voice in fighting oppression and asking critical questions. It’s about sharing stories and experiences and cultures in order to better understand each other. It’s about creating communities who are concerned with culture, both in the future and in the present. Students who value the arts understand humanity. They may become artists themselves, but they will definitely become cultural ambassadors—citizens who will vote for cultural policy, join not-for-profit boards, donate to arts organizations, subscribe to their local theatre or gallery—all while carrying on regular, non-artistic jobs.

Budgets are tight, and we can only ever do what we can do. There are few fields that produce as much work with such limited resources. But sometimes I think we could do better for our sector overall if we spent a bit more time being as creative with the integration of arts education programming. The longer we put off investment in arts education, the greater the gap becomes. The wider the gap, the more difficult our marketing will be and the fewer bums that will find themselves in seats.

Effective arts education creates the kind of people I want to be our next generation of leaders across many sectors: business, political, environmental, athletic, and cultural. People who have had authentic arts experiences understand how to innovate, how to be creative, and how to be empathetic. They’re good people and I think we need more good people in the world.

Comments