Chekhov, Words, and the Long-Distance Relationship

“I find it nearly impossible to respond to what I’ve read. I think it’s like watching a good play. I don’t want to talk about it until I have given it a chance to be absorbed entirely. Your words are utterly compelling. I hear your voice so clearly…and it moves me.”

I wrote this to my future wife, a writer who I barely knew. Over the course of many months, I had become addicted to her words.

Heidi Reimer and I met, briefly, in 2002, and for the following nine months we wrote each other letters, our courtship unfolding through words on a page. Or rather the very first letter, sent by her, was on a page—an actual page written on with a pen and mailed with a stamp—though the subsequent letters were emailed. But they were long, thought-out documents, with days or a week between each as we took our time composing and responding, carefully unveiling ourselves to each other.

Artists are used to long-distance relationships, relationships that are hard to sustain. The words used in communicating become important. Actors and writers use words, treasure words, mould words. Words are the clay of their art.

Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper wrote to each other. He was a writer, she was an actress. They were frequently separated by her work and his health. Their love story unfolds in their letters. The play based on these letters is called I Take Your Hand in Mine…

I am playing Chekhov in this play, in a mirror image of my own experience. This time I’m not the actor, but the writer.

Chekhov met Olga for the first time at the Moscow Art Theatre for rehearsals of his play The Seagull. He was immediately attracted to her even though he mistrusted actresses. (“Actresses are cows who fancy they are goddesses … Machiavellis in skirts.”) Olga was ambitious, impulsive, talented. She loved life and threw herself headlong into her all-consuming passion: the theatre.

I also met Heidi for the first time in a theatre.

I was playing Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing at a small theatre in the mountains of West Virginia. Heidi and her best friend were housesitting in an adjacent town. They came to see the play.

Afterwards, as actors and audience mingled in the lobby, I noticed them. The friend was outgoing and vivacious. Heidi was the opposite. Tall and dark, she sat quietly observing, hardly noticeable, until she laughed. Her smile, with a gap between her front teeth, illuminated the room.

I was transfixed.

Over the weeks of the play, we kept bumping into each other—across a street, in a dance club, at a party… but I avoided her. She was too young. Too beautiful. Too innocent.

And yet, my attraction to her was overwhelming.

At the show’s closing party, she appeared out of nowhere. She sat down beside me. We talked… And talked… Easy, free, relaxed. We were surrounded by people, but we were alone.

I believe it was that same initial spark of attraction that drove Chekhov and Olga in their first months of letter-writing after that Seagull rehearsal. Olga’s letters are passionate and heartfelt; Chekhov’s are teasing, mockingly flirtatious, and yet reserved. A notorious womanizer, he had up to that point managed to avoid committing to any woman.

Two months after that first conversation Heidi and I had, I received a handwritten letter from her—an unusual occurrence even in those dark old days of 2002. I was intrigued. Why had she written? She told me she felt a connection; a meeting of two quiet people who recognized in each other a kindred spirit.

As with Chekhov and the ten-years-younger Olga, it was, at first, a tentative dance.

Eventually came the sharing: our lives, our histories, our longings. For me, it was an existence of constant travel as a lifelong actor, and a string of broken relationships. For Heidi, it was a deep yearning for artistic fulfillment and a marriage to God that had recently been dissolved.

Without constant personal contact, we counted the days between each new correspondence.

“What’s happening? Where are you? Your writer has been forgotten,” Chekhov admonished Olga.

Over nine months, as I toured the States with the Aquila Theatre Company’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Heidi returned to university in Toronto, our relationship blossomed through the words we wrote. Like Olga and Chekhov, we encouraged one another in our art.

Chekhov: “I will never take you away from the theatre.”

Olga: “Write each word, each thought… and remember, we’re all waiting for them.”

The support and the caring were felt through the written word, along with a remembrance of that initial bright spark of physical attraction.

We deliberately avoided the phone. We knew we couldn’t be as eloquent. There’s a safety net for introverts in the written word.

When my touring production finally came to the New Victory Theatre on 42nd Street in New York, Heidi flew from Toronto to meet me for the first time in nine months. I greeted her with a single yellow rose.

She stayed for three days. The day after she left, my production closed and I boarded a train to follow her back to Toronto.

Olga and Chekhov married in secret in Moscow and sailed down the Volga River. Heidi and I married on the banks of a Northern Ontario lake. A full moon turned the lake silver.

For a wedding present she gave me a bound copy of our correspondence.

The title: I Hear Your Voice So Clearly…

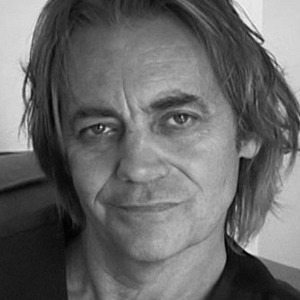

Richard Willis is starring in “I take your hand in mine…” which runs until April 23 at Tarragon Theatre.

For tickets or more information, click here

Comments