Dengbêj | Storyteller

Please note: this article was written collaboratively. Thus, we often refer to ourselves in the third person.

In the mountains of Kurdistan we sat in a circle on white plastic chairs, on a small dirt platform carved out of a steep mountainside.

Cowbells clanged nearby from grazing cows, and there were big black and orange grasshoppers slowly crawling around. We were surrounded by tall, giant trees, with books arranged in the pockets of their trunks. In one corner of the camp, a fire in a handmade oven kept the tea warm for our gathering. The Kurdish female freedom fighters all wore green uniforms, with brightly coloured sashes around their middles (and some wrapped around their heads). They popped sugar cubes in their mouths, chased with sips of hot tea, and asked us questions about why we were there, about theatre in Canada. They talked about how theatre is an important tradition for the guerillas, bringing stories of oppression and women’s rights to perform for the villages.

We traveled to the Qandil Mountains in Northern Iraq to write a play in 2018 as part of a residency at Nightwood Theatre.

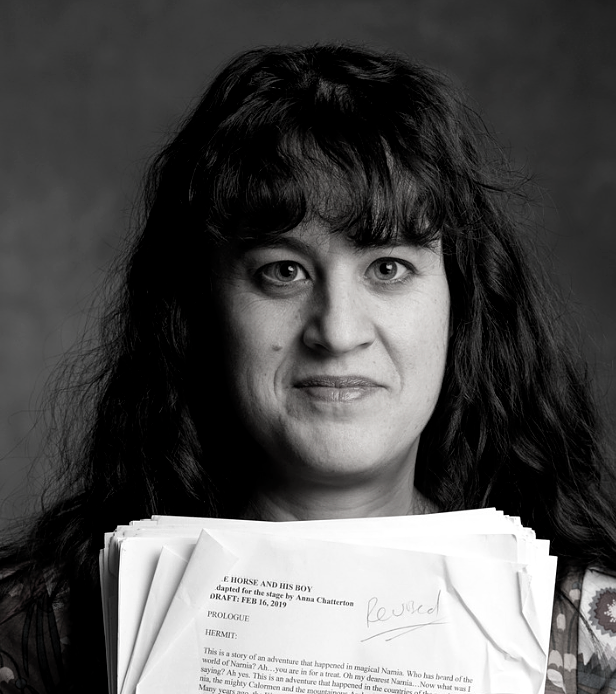

Anna had learned about the Kurdish female fighters who drove ISIS out of Rojava during the siege of Kobani in 2014. She was struck by the fighters, and inspired to learn that they had all-women units with female leaders. Being a theatre artist, Anna had the creative impulse to make a play about them, but had no idea how to go about it. After lengthy research and meetings, Anna had the great luck to meet her collaborator, Shahrzad, who had gathered and documented the stories of the Kurdish fighters for her films, podcasts, and articles for many years.

Originally, before traveling to Kurdistan, Anna had thought the play could be about a female Canadian soldier and a Kurdish female freedom fighter: she could see the two fighters talking.

But what was the play about?

Shahrzad quickly banished Anna’s (lame) idea, and instead spoke to her about the concept of having her and the fighters together on stage. It made Anna realise that in order to write about the fighters, she had to meet the women in person. Shahrzad had never written a play before, but had always loved theatre and was happy to go see her friends in the mountains.

One of the four camps Shahrzad and Anna went to in the mountains was the Artist Camp, which had a small group of artists/fighters living there. Freedom fighters who were also artists. Sitting in the shade, surrounded by the natural beauty of the brown mountains, the fighters spoke about the tradition of Dengbêj, being a singer and storyteller, going village to village in Kurdistan to bring stories and songs to the villagers. Even now in big cities students do political street performances or in parks to tell their stories, and share their experiences. As Shahrzad translated for Anna, the necessity and value of theatre suddenly felt epic and moving. Living in Canada, sometimes making theatre can feel unimportant. It was refreshing to remember the impact theatre can have on an audience, that theatre can change people’s lives.

The fighters spoke about fighting and art and activism all in the same sentence.

As gentle, soft, tambour musician and songwriter Bermal said: “We use art as bullets. My Tambour is my weapon.”

As the large-boned, wide-smiled, generous, kind, poet fighter Medya told us: “I write because I want my writing to become like flogging. And make people’s hearts full of pain. I want my pen to transfer our pain and our life. I want as much as seeing the brutality of war burn my heart, that I can burn other’s hearts with my writing. And like that they will maybe stop feeling sorry for us.”

As kind-eyed, mischievous, humble Peyman articulated : “In the history of Kurdistan, Kurds were not allowed to write their own history, so we taught our history to the next generation through songs. We sang about our pain, oppression, injustice and our heroes. For us it is important to sing, write poems, create art and fight at the same time.”

Our time hosted by the fighters in the mountains was full of love and admiration, delicious food, much laughter, great challenges, layers of complexities, and deep learning. The women were so warm and generous. Though Anna couldn’t speak Kurdish or Farsi, she felt close to them. Shahrzad, who had stayed with them many times over the years, felt like she was visiting family.

These women who have so little, and whose lives are so difficult, were so gracious and kind to us, the best hosts in the world. We were protected with great care. But we had to leave early due to Turkish bombing in the mountains close by.

Once we came back from our trip, it felt clear that the journey and complications that occurred on the trip in Kurdistan were important to put into the play as a frame — as a way to contextualize the stories of the fighters we met.

Shahrzad interviewed many fighters we met while we were there and recorded their stories.

Back in Canada, she translated all the stories. It felt clear which stories we wanted to share — the women who we really connected with while we were there, were drawn to, whose stories were so compelling and vivid. Tinda, who was forced to leave her children due to oppressive traditions and joined the fight; Medya, who had witnessed horrible atrocities in Rojava and Afrin; joker Ronia, who would have graduated high school at age 13 but was imprisoned and then joined the struggle; Bermal, the musician who had lost so many comrades and wrote songs about them and their lives.

We began the long process of writing the play. Anna parsed her writing from her extensive journaling while in the mountains, and we began to revisit and document our memories, guided by Nightwood Theatre’s artistic director Andrea Donaldson. It was after the first reading with actors where Shahrzad and Anna made the discovery that the “characters” of Shahrzad and Anna should be played by themselves.

However, that first reading of the play was three hours long. There was a long debate about what to do; just make it a durational piece? Include an intermission, or two intermissions? Cut it down to make it a more curated and shaped experience? We had always had the instinct to do the play outdoors, same as the fighters who live outdoors all year round in the mountains, and once the pandemic came along that seemed an even more obvious choice. However, to ask people to sit in uncomfortable seats for longer than an hour was asking a lot. Even if it were to take place indoors, what could an audience engage with? What parts of the stories could be highlighted for a gripping theatrical experience?

We compromised by making a three-hour podcast of the full stories and then, with the help of our director Bea Pizano and support of Andrea Donaldson, we began to cut and tighten the play.

But the cutting of the fighters’ stories was particularly painful for Shahrzad: at one point she wept that each line we cut was like a dagger in her heart, for the women were so dear to her. Anna and Shahrzad had both fallen in love with the fighters, missed them so much and cherished their words.

Focusing on which parts of the women’s stories were essential to share, line by line, we arrived at a one-hour play.

Children Of Fire is going on stage during a time when the Kurdish mountains and many Kuridish villages in Syria and Iraq are under constant bombardment. The Qandil Mountains and other mountains in Kurdistan, where we visited in 2018, have been bombarded by chemical weapons many times in the past couple of months. We think of Kurdistan’s upright mountains and how they bear the days under the cruel bombings carried out by Turkey. Shahrzad is thinking of her young daughters and sons over there whose stories must be retold so that the day might come that no youth sacrifices their sweet life for a better world.

We feel heartbroken when we observe that the world is in complete silence, but at the same time deeply hopeful when here in Canada a group of women — a group of artists with different backgrounds — are daring to speak about stories that are evidently not important to the news anymore. Stories are getting told — stories of the beautiful and brave young women like Ronia, Tinda, Medya, Bermal, Ciwana and Peyman.

Children of Fire is a story of kind women who fight generously and relentlessly for a better world. This play would not have been possible without the friendship and trust of these humble and unclaimed heroes.

With Children Of Fire, we act as Dengbêj outside of Kurdistan, telling stories that would not otherwise be heard here in Canada.

Comments