Meditative Dreamscapes

The Aorta is a former funeral home, repurposed into a meditative dreamscape for the latest Outside the March immersive theatre experience, TomorrowLove.

The many rooms inside the four-floor building, like chambers of the heart, provide the settings within which we explore the hypothetical impact of imagined future technologies on all manner of relationships. Performers and attendants act as guides, as the audience, semi-voluntarily, regularly sub-divide and converge, moving from space to space, watching three or four plays in about an hour and a half.

There are fifteen plays, each featuring two of the eight actors that comprise the TomorrowLove ensemble. Each character is rehearsed by two different actors, the characters specifically written genderless for casting fluidity. Each play can be presented in four casting combinations. A dance-infused lottery system at the beginning determines which plays each actor will perform on any given night, and with whom.

For the performers, it’s been demanding, as the rehearsal process required us to spend half the time working on our feet and the other half observing our actor twins playing our same parts.

Watching another actor play roles that I also play has been quite instructive. It shortcut some of the process of interpretation, since seeing someone else rehearse those roles made it easier to understand the breadth of the stories and the arc of my characters. We’ve been directed especially to maintain an acute awareness around how certain gender combinations require a vigilance, so as not to tilt the balance of argument in each play.

It wouldn’t have been possible, in the time we had, to rehearse all possible combinations of all plays as thoroughly as we might if we were the sole torchbearers of each part. And because wildly different interpretations of the same character could be a confusing adjustment for our nightly-chosen scene partners, it was decided early on that we should all find common interpretive ground with our performer twin for our shared characters.

But given the broader differentiation between the actors, in gender or ethnicity, or more significantly, in our nuanced differences as performers, it became clear that we would be adjusting nightly anyway.

Katherine Cullen and Cyrus Lane. Photo by Neil Silcox

Naturally, familiarity with the material would help us get comfortable with the rhythms of each play, but due to the lottery-based system of nightly play selection, we could end up performing some plays many nights in a row and rarely performing others. Also, since there are four possible combinations of performers per play, there’s no guarantee that the person I performed the scene with at the previous show will be whom I perform it with the next time.

This creates a tightrope dynamic in performance. It sets up an energy and spontaneity reminiscent of the electricity underlying improvisation, a freedom to the process I experienced regularly while on the mainstage at Second City. There, during rehearsal, we would roughly sketch out an idea for a scene, leaving lots of room for play, and that evening, see what emerged from the dynamic. As a consequence, our scenes, as we felt our way through them, would have a tension that contributed to their comic success.

Similarly, when I was performing in Colin Munch’s True Blue, a dramatic improvised procedural cop show, none of us in the cast knew who would end up as the murderer. Every ad-libbed exchange was full of clues about how to advance the plot, but only one step forward at a time. That dramatic tension in True Blue feels especially familiar in this process. But this is not improv in the purest sense, where the performers are simultaneously actor, playwright, and director, inventing everything moment to moment.

In improv, gender and race, and even species, are necessarily fluid since everything is based on believing what the improviser declares to be true. In an instant, you can introduce yourself as a talking cockroach, proclaim you are running for political office, and become the first cockroach President of the United States. Scripted theatre can do that too, but it generally has a more formal introduction to the idea than a simple ad-lib declaration.

Where progressive theatres are casting with an eye towards diversity, inviting the audience to rethink gender, race, and other trappings, there are challenges. The language in, say, King Lear, currently being played by Glenda Jackson, refers to Lear as a man, so do you change the character’s gender, erase the actor’s gender, or make no concessions and, like in improv, leave it to the audience’s imagination?

TomorrowLove playwright Rosamund Small’s script is different because there is no race or gender assigned to any character, nor are the relationships hetero- or homonormative. The stunning result of this is the profound ways in which the plays are equally compelling and honest, whether played by two women, two men, or a woman and man. As one of the actors, Paul Dunn, says, “One of the things I think is special about this experience of sharing roles and alternating partners is that we each get an opportunity to play outside of our usual actor ‘box.’ We all get to be called seducers sometimes, and we all get to be desired. All of us, in one scene or another, get to be called beautiful, sexy, and perfect.”

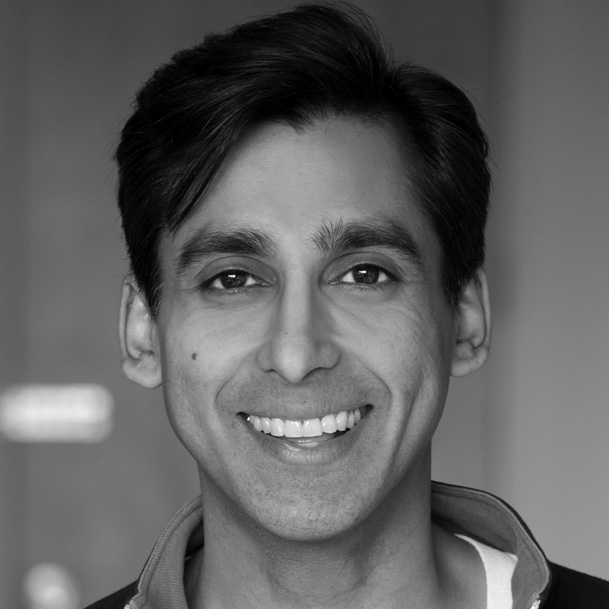

Anand Rajaram and Paul Dunn. Photo by Neil Silcox

In most of these plays, the greatest value is in recognizing how inconsequential race and gender can be in the casting. It is a rare privilege to be afforded the opportunity to make my race and gender neither invisible nor central.

No one in the cast has ever attempted anything like this before. Naturally, we are nervous. There are the standard nerves of remembering lines, blocking, and director’s notes, but then there are the extra challenges of adjusting to our nightly scene partners and remembering our movement through the building, which changes with the lottery result, as we guide the audience through The Aorta.

With the nerves comes liberation—the kind offered by improv audiences, who recognize the uniqueness of the form of performance they are watching and provide a safety net of assurance that they will catch us if we fall, as long as we do it honestly, our fear unmasked. At least, that is the hope.

The technical and design elements of the show have created an otherworldly foundation for the immersive experience. This is theatre as architecture, the dressing of the building and movement through it affecting the viewer’s sense of both intimacy and isolation, prepping them for plays that similarly awaken their emotional states.

We performers, as we move with reverence through The Aorta, the almost monastic space, feel like we are a part of the structure of the building, like red blood cells swimming through arteries. We are the memories and secrets that never leave the heart chambers. The audience enter as breath, bear witness, and then carry our stories out.

TomorrowLove is on at The Aorta (733 Mount Pleasant Road) until December 18.

Click here for tickets or more information

Comments