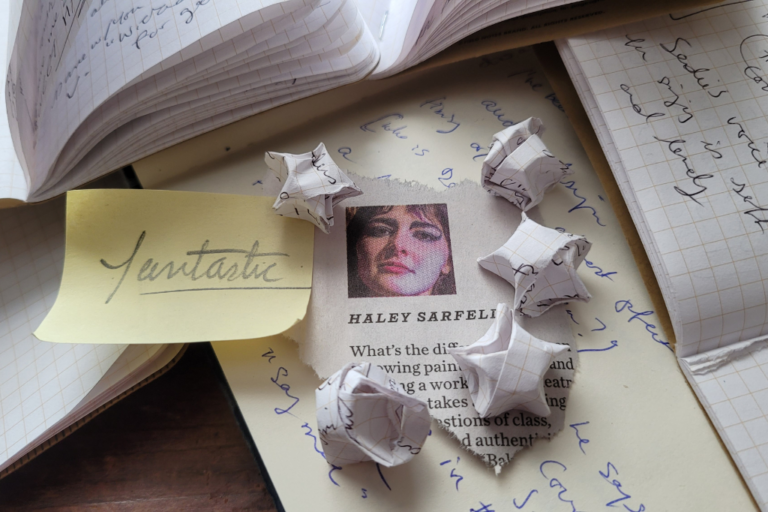

An open letter to lighting designers

Dear theatre directors and lighting designers,

At a time when theatres are struggling to get their pre-pandemic audiences back, it’s shocking that strobe lights are still featured in so many productions. They might seem like a splashy yet innocuous design choice, but they are at best a barrier for potential audience members — and, at worst, they have painful consequences.

Since a 2010 brain injury made me sensitive to overwhelming lights and sound, I’ve been slowly unspooling what it means to make spaces accessible. As an industry, I hope that we’re on a journey towards making theatre more accessible for all. Most Toronto venues are wheelchair accessible, but only because disabled people have tirelessly advocated for the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act and continue to press for accessibility in the theatre industry.

Unfortunately, when it comes to lighting design, many lighting designers seem to have lost the memo on how aesthetic choices like strobe lights can have drastic effects on photosensitive audience members, other artists, and even front-of-house staff.

People with migraines, autism, or brain injuries can experience pain and discomfort when they see strobe lights, particularly in a setting where everything is dark but the stage.

Unfortunately, when it comes to lighting design, many lighting designers seem to have lost the memo on how aesthetic choices like strobe lights can have drastic effects on photosensitive audience members, other artists, and even front-of-house staff.

Flashing lights can even trigger seizures. One in 100 people have seizure disorders, and within that group, as many as five to 13 per cent have photosensitive triggers. What surprises many is that there are over 75 different types of seizures — so even if a production isn’t interrupted by a clear medical emergency, someone might have had a less noticeable seizure, a migraine, or vertigo, which are very real medical episodes despite their quiet nature.

While I’ve been sensitive to flashing lights for over a decade now, the relative calm of my COVID lockdown environment made me much more aware of the physical and neurological pain they cause me. I also have a seizure disorder. My epilepsy is not photosensitive, but my triggers are related to stress, which can include overwhelming lights or sound. Even before COVID, I avoided all shows with strobe lights in their content warnings.

Most recently, I was psyched to attend That Theatre Company’s productions of Angels in America Part One and Part Two at Buddies in Bad Times, as I had never attended a live production of Angels and have always wanted to. Buddies posted a strobe light warning at the box office and volunteers told me when to expect them so I could close my eyes. These strobe lights prevented me from viewing most of the magical realism scenes in the plays, which was incredibly disappointing. There were also milder flashing lights that I was not warned about, in scenes which I was also not warned about. I felt cheated out of fully experiencing these plays which I had long wanted to see.

Back in September, I had to give away tickets to Mirvish’s production of Six due to the pain that could’ve been inflicted by the show’s pop concert-adjacent design, which apparently included “flashing lights, strobe effects… and loud music throughout.”

Even theatres usually committed to accessibility struggle with this issue. As good as their intentions might be, some theatres are still in the process of learning how to adjust co-productions and tours which have already been designed to include strobes. Earlier this year, at Theatre Passe Muraille (TPM)’s presentation of Delinquent Theatre’s Never the Last, I was warned less than five minutes before the show that there would be strobe lights. There were no warnings in the lobby or on the website. Thankfully, the strobes in that show were brief and only caused minor discomfort, but had they been prolonged, I might have felt the effects for days afterward. While all of TPM’s shows make use of “relaxed” performances, presentations of shows not developed in-house are harder to adjust, especially if accessibility isn’t considered early on in the design process.

When I brought up the issue over email, TPM took responsibility for the error and promised to better communicate warnings for all future shows; however, strobe light warnings are only helpful for deciding whether or not to attend a specific production.

Including a strobe light warning is like noting that a venue is not wheelchair accessible. When it includes strobe warnings, the theatre company has recognized that its show is inaccessible, and rather than fix the problem, it warns disabled audience members so we know not to attend. This is incredibly insulting and tells us that companies do not want us in their spaces, even though the problem of strobe lights could easily be fixed.

Would you rather eschew the use of flashing lights, which would ensure your production is a safe and accessible space, or continue using them, excluding audience members and potentially triggering seizures, discomfort, and pain?

After all, designing a show without strobe lights costs nothing. It’s the easiest accessibility measure and can be applied to all the shows in a run. While there can (and should) be more relaxed and American Sign Language-interpreted performances for every production, these are more cumbersome adaptations. The most cost-effective, unintrusive accessibility measure is to forgo the use of strobe and flashing lights entirely, which would not interfere with the show whatsoever.

Elements of universal design like this benefit everyone. Accessibility measures (like elevators, closed captioning, accessible toilets, and curb cuts) don’t just benefit those who need them to be able to participate at all. Strobe lights can cause eye strain or discomfort in people who may not have disabilities per se, but who may be prone to headaches or are simply tired. Audiences won’t notice the lack of strobe lights, but it will be much better for their vision in the long run to avoid these visual stressors.

Dear designers, directors, and other collaborators: it comes down to this.

Would you rather eschew the use of flashing lights, which would ensure your production is a safe and accessible space, or continue using them, excluding audience members and potentially triggering seizures, discomfort, and pain?

Forgoing strobe lights will make all audience members more comfortable. They may look cool, but they are a source of eye strain for everyone, not just those who are particularly sensitive to them. Continuing to use them is a selfish, exclusionist act.

I want to attend theatre. You have to want me there, too.

Hannah, thank you for writing this. Your comparison with disability access is perfect!

I have photosensitive seizures that are under good control but strobe lights are a definite trigger.

I too love theatre. Once in a while I take a chance and go if friends have seen the show and tell me it’s very brief. Other times I’m afraid of the risk.

Maybe enough of us will be heard by lighting designers.