Revitalizing Japanese Canadian Identity

You may know some of the facts surrounding the forced removal and internment of roughly twenty-two thousand Japanese Canadians from the coast of British Columbia during World War II. Perhaps you know of the evacuation policy that granted the BC Security Commission possession rights for all Japanese Canadian personal and commercial property within a hundred miles of the coast, and the extent to which the population was dispersed following the war, settling where they could east of the Rockies or face deportation to Japan. And although no Japanese Canadian was ever charged with treason, the population remained disenfranchised and labelled “enemy aliens” until 1949. Perhaps you know that official redress was successfully pursued and awarded in 1988 after a decade-long campaign, marking the end of official policy dealings between government and Japanese Canadians.

But what do we know of Japanese Canadians in 2019, now into their fifth and sixth generations? Our present predicament, as a people and a culture, is still deeply affected not only by our internment history (both known and unknown, even amongst ourselves) but by how the first generations reacted to that adversity: with the mantra, shikata ga nai—it cannot be helped. These words are at the heart of the older generations’ survival and perseverance, but they are also what have led younger generations of Japanese Canadians to our ambiguous relationship with the past, one that tempts us toward an abandonment of cultural memory and identity.

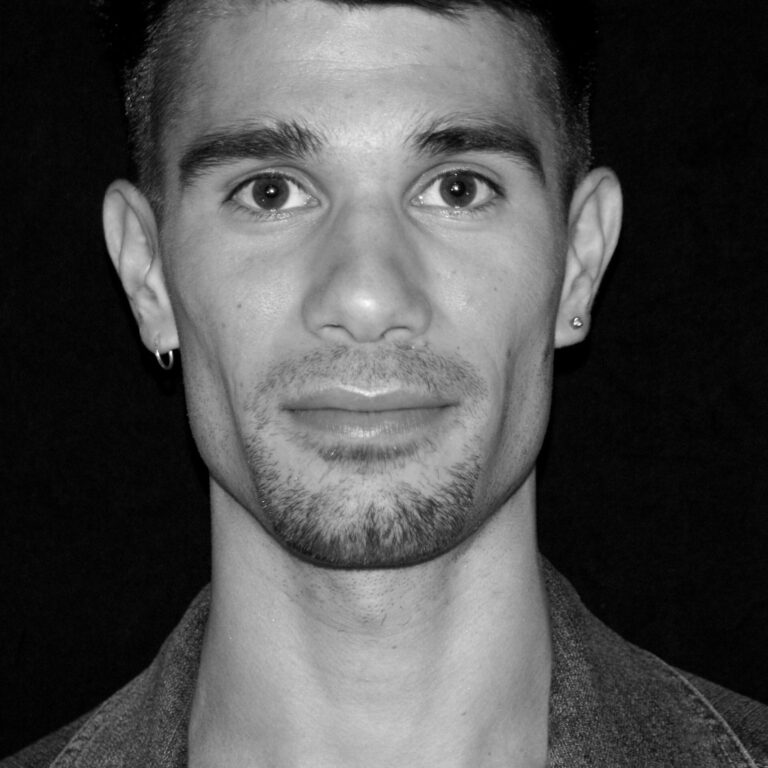

Julie Tamiko Manning and Matt Miwa. Photo by June Park.

As much as shikata ga nai served as a coping mechanism and as a cultural practice, this mentality was, in the aftermath of internment, pushed past its limits. Throughout the generations, internment was left behind, no longer spoken of, and the main prerogative of shikata ga nai became to assimilate into the “Canadian way of life.” While this mentality did push younger generations to persevere and survive in the context of our new lives, it also turned sour.

In my father’s generation, the third generation, the pressure to balance shikata ga nai with the incongruent social realities of new—and racist—”assimilated life” produced outraged youth. Neither shikata ga nai nor greater society offered space to engage with this outrage, and so it remained a private, corrosive burden, leaving unhealed wounds. The cauterized outrage of the third generation psyche has been passed on to following generations, and our collective memory smoulders with unspoken anger.

Today we are a diluting ethnicity and culture. Amongst visible minorities in Canada, Japanese Canadians have the highest rate of intermarriage, which according to the 2006 national census is into the seventy-five percentile range. Our fourth and fifth generations, now half, quarter and one eighth Japanese, stand far enough away from history and straddle enough ethnicities and cultures that, without an articulated sense of Japanese cultural pride, it is easier to embrace the resolved cultural identities of their other kin.

What will become of Japanese Canadians?

The Tashme Project: The Living Archives, which premiered in May 2015 at the MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels), is a theatre piece Julie Tamiko Manning and I have been creating for the past five years. Through Tashme, we present a verbatim oral history of internment and its aftermath, edited together from over twenty interviews with nisei (second-generation Japanese Canadians) from across the country. Breaking through the practice and history of silence in which we were raised, we sat down with our elders and asked for stories of internment. Well practiced in shikata ga nai, the nisei themselves were all reluctant at first, but what was promised to be half-hour interviews almost always extended to two-hour sessions. Our lifelong curiosities were finally satisfied, and the murky picture of our families’ past—our legacy—came to light.

For those who were raised in the midst of cauterized family wounds and who have been alienated from the past, theatre holds multiple potential horizons in the search for memory, identity, and community. Internment was a defining collective experience, yet the ways in which we do or do not remember it remain at odds between generations. And so the prospect of intergenerational dialogue gives voice to our theatre with fierce feeling, commitment, and empathy for our kin. This mission lies at the heart of our theatre creation process.

The Tashme Project (MAI production). Photo by June Park.

As theatre-makers, we seek to create a space and an authority whereby a community can speak earnestly and sincerely to itself, and look to dissolve the trepidation—read shikata ga nai—that inhibits our attempts at meaningful dialogue. We seek to look beyond the achievement and the history of redress into the inarticulate, shamed, and outraged inner world that persists unresolved, both within ourselves and in our elders. We implicate the nisei, our elders who as children persevered through internment and who now witness our great cultural schism with alarm. We openly reveal our desperation: “Memory Keepers,” we say to them, “there is more value and need in your personal histories than any of us have ever acknowledged. We do so now!”

When we convey the twenty-odd testimonies of our elders, it is an invitation to communion for Japanese Canadian audience members. Given the extreme personal connection and prerogative both Julie and I have as performers and as non-fictive stage figures, we can be observed as both reciting and overhearing our elders’ stories. This simultaneous speaking provokes a visceral emotional and spiritual transformation in us, and we offer this transformation as a gesture of love, reverence, and faith to our kin, and as a manifestation of the ‘wounded healer’ archetype to the audience at large. We appeal to all of our audience to interpret our recitations in a sacred context.

Like many children of immigrants, we respect and honour the struggles of the past

Through The Tashme Project, we want to articulate who contemporary Japanese Canadians are, and who we can become vis-à-vis our confrontation with the past and with each other. We want to affirm that it is perfectly fine if we are unable to resolve our anxieties about past and about our present cultural identities. We want to affirm that even our willingness to confront it, haphazardly and through highly personal prerogatives, cultivates good values: compassion, patience, love.

Like many children of immigrants, we respect and honour the struggles of the past. We have not transcended these struggles, nor do we yet know how, but we carefully contribute to the great Canadian “child-of-immigrant” tradition of articulating that inescapable sense of duty toward one’s elders when a younger generation lives with access to more possibilities, and opportunity. Lastly, because all first-wave immigrant Japanese Canadians live under the dread of becoming a disappeared race—losing culture, history, ethnicity and language—we want The Tashme Project to offer an example of the life force of a vitalized, younger, Japanese Canadian generation.

Comments