See Me

High school is rough to say the least; dealing with bullies, the pressure to fit in, to be cool or popular, all while negotiating with a changing body and hormones that just won’t quit. Feeling like nothing you do is good enough, and that everything you do matters and doesn’t matter, all at the same time—it’s a nightmare. Now imagine dealing with all that in a black female body and not just any black female body . . . but a dark-skinned black female body.

Some of you outside the black community may not understand what I mean by the distinction of dark-skinned, or think that “black is black” and that it’s all the same, but those of us who are in the community know differently (whether we choose to acknowledge it or not). Black is not just black. We are not all the same. From back in the day until now, depending on how dark or how light a person is on the colour scale, their journey in this world will be very different.

As a dark-skinned black woman I experienced this firsthand, particularly during my high school years. At that time it seemed like my skin was always something to talk about. People teased me for being “too dark,” they called me monkey or “black like night” or they didn’t want to touch me because they feared my blackness would rub off on them (as if my skin was some kind of tanning lotion). When I turned on the TV or looked through magazines, all the images of successful black women were of women who were at least five shades lighter than me. Boys wanted nothing to do with me. It felt like I was constantly overlooked for the lighter-skinned girls. I would hear them say things like “I don’t like dark-skinned girls” or if they complimented me it was usually “you’re pretty…for a dark-skinned girl.”

Keep in mind all of this information is coming at me at a time in my life where I am the most vulnerable, the most irrational, the most insecure and unsteady version of myself. During a time when I am trying to figure out who I am in this world, while everything in this world is telling me that I, as my natural self, am not enough. That what I am is not beautiful or desirable and that I am, for lack of a better word, a freak. The dark skin that holds me together had been branded as bad through no fault of my own and if I were lighter, things would be different.

I thank God that I was able to overcome other people’s narratives about my skin tone; that I somehow found resilience and made it through high school. However hurtful people’s words and actions towards me were, I’m glad I never took my pain out on my skin. I have grown to love my dark skin tone and it is now the thing that people compliment me on the most.

But I feel like my story is not in the majority. The reality is that a lot of young dark-skinned girls, not just in the black community, but in the coloured community as a whole, have internalized the narrative that “lighter is better” and end up seriously harming themselves in the pursuit of that standard. Whether it’s using harsh chemicals to straighten coarse curly hair or skin lighteners (aka bleaching creams) to change the tone of their skin, dark-skinned girls all over the world are resorting to drastic measures to attain features that are completely foreign to who they are, because they have been led to believe that those things will make them popular or more desirable or give them a better life.

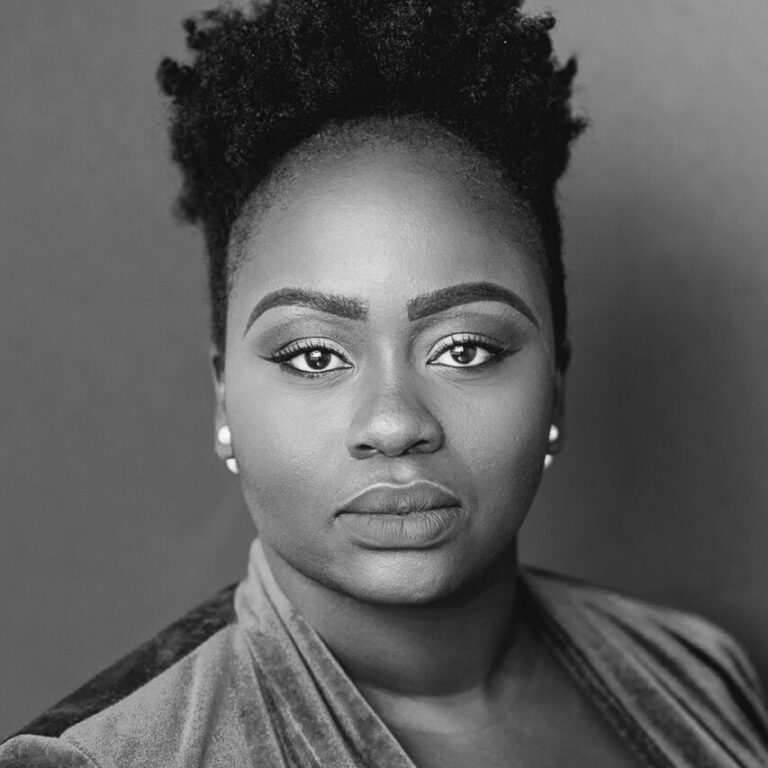

Natasha Mumba (Paulina) and Melissa Eve Langdon (Ericka) / Photo by Cesar Ghisilieri

Jocelyn Bioh tackles this issue head on in her comedic play School Girls; Or The African Mean Girls Play, when the main character Paulina (the most beautiful and popular girl in school) has her social status and her future outside of the school threatened with the arrival of a new student Ericka (a beautiful fair-skinned biracial girl). Although the play is a very funny fictitious story about a few days in the lives of six teenage girls at an all girls boarding school in Ghana, West Africa, the series of events that occur touch upon the very real issues of shadeism that many young girls and women face today.

We have been working on School Girls for a few weeks now and I have been thinking a lot about representation and how much it matters. After we read the play around the table during our first week, I couldn’t help but think that maybe if Paulina had one person in her life that could show her a different narrative, or if there were more positive images of dark-skinned women or even ONE image of a dark-skinned woman, that maybe she would have had a better chance of building a stronger sense of self. She would know that she is not alone in the world, that she exists, and that women who look specifically like her have value too. At the end of the day I think that’s what we all really want—to be validated to be seen. And that doesn’t change after high school.

Natasha Mumba (Paulina) and Melissa Eve Langdon (Ericka) / Photo by Cesar Ghisilieri

I’m thirty-five years old and the first time I truly felt I saw myself reflected back to me was a few years ago when Lupita Nyong’o won her Oscar for best supporting actress for her performance in Twelve Years A Slave. I remember weeping, not crying, but weeping when they called her name. I felt like they had literally called out Akosua Amo-Adem. For the first time in my life I witnessed a young, dark-skinned, natural-haired, beautiful African woman being rewarded for excellence in the very thing that I was doing with my life. That moment reassured and PROVED to me that my dreams are possible and that my dreams are valid (which is what Lupita Nyong’o said in her speech).

If I, as a fully-grown woman, could have such a visceral response to that moment in time, imagine a sixteen or eighteen-year-old girl in high school. This is why specificity about the way we represent black and brown bodies on our stages is so crucial. Having stories that speak to our uniquely lived experiences told by people who look like us gives us hope and inspires us to keep going. It’s as basic as one plus one equals two. So let’s stop the “talk” about more representation on our stages and in our industry and let’s just do it. Let’s do it better and let’s do it often. My hope for the young girls that come to watch this production of School Girls is that they feel validated, that they witness themselves in me and the seven other talented, beautiful, different black ladies on stage and that they walk away feeling like they have finally been heard and seen.

Comments