Screwball Times Call for Screwball Comedies

Comedy, we may say, is society protecting itself — with a smile

—J.B. Priestley

I woke up this morning to the news that the touring production I am currently performing in has been cancelled. It is the final (and most heartbreaking) activity in my life to cease. I have already been released from my other confirmed contract. Now, I have no upcoming work or income, and, like so many others, have become an unemployed artist overnight. Oh, and my apartment has bed bugs.

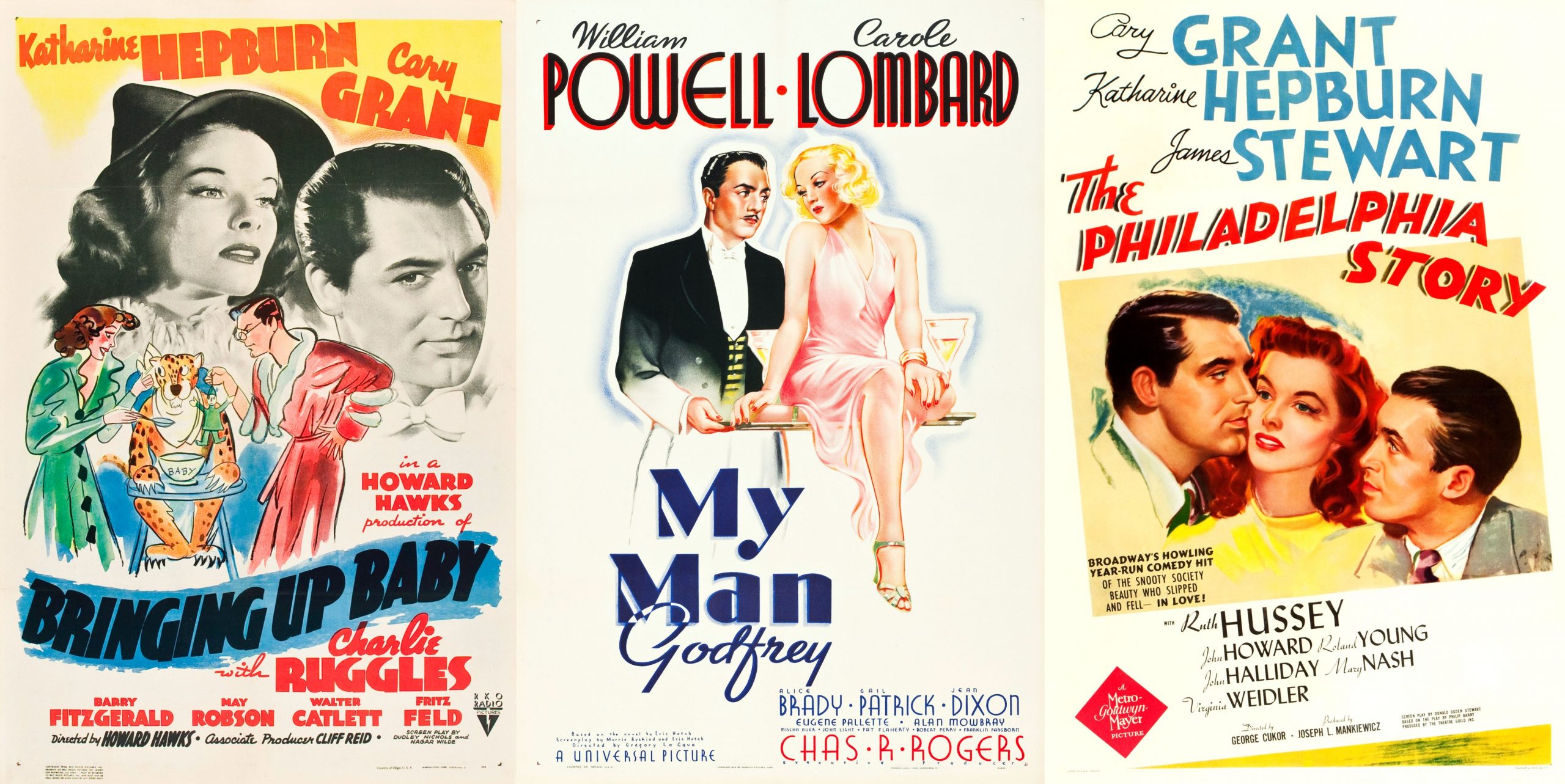

It is with noticeable irony that the play I was performing in is called Screwball Comedy by acclaimed Canadian playwright Norm Foster. It premiered at The Foster Festival in 2017 in St. Catharines, Ont. and is a nod to the beloved genre that emerged during the Depression. You may have seen or heard of such films as Bringing up Baby, My Man Godfrey and The Philadelphia Story — films that were humorous and silly and strived to lift people’s spirits during a financial crash. Because, when the going gets tough, the laughs start rolling. Much like right now. Comedy is helping me deal with my stress. Stand up specials, old British shows, crass cartoons…the laughs alleviate the anxiety. A look at my Netflix account this week shows programs like The Office, Schitt’s Creek and Brooklyn Nine-Nine trending. Laughter, it would seem, is the panacea for pandemics.

A key aspect of screwball comedies is how they depict class division. Typically, the stories portray things going wrong for out-of-touch rich people, and audiences watching the absurd events unfold laugh wholeheartedly at their expense. (Keeping up with the Kardashians, anyone?) In this time of social distancing, the class divide certainly strikes home. Self-quarantining is a privilege many people don’t have; gig workers suddenly bereft of income are out in public scrambling to make ends meet through a myriad of ways like childcare, landscaping, delivery, etc.; public transportation users who don’t own cars have to rely on busses to get to the grocery store; people who live pay cheque to pay cheque can’t afford to stockpile supplies.

But through it all, screwball comedies are about love, which is what I’m clinging to right now during this chaotic time. I have so much to be grateful for. I, and my loved ones, are healthy. I have a supportive partner who I can stay with for as long as I need. Let’s just hope a battle of the sexes—also at the heart of every screwball comedy plot—doesn’t materialize. (It’s early days yet though). Unlike the audiences in the late 1930s and early ’40s, I am not watching comedy to distract myself from the literal horrors of war outside my window. I don’t have five kids to feed—as my grandmother did. I am willingly self-isolating with the comfort of food, electricity, and running water. For the lucky ones, this period of social distancing will be a reset, a reprieve. The part of me that is not depressed (because this is an extrovert’s hell), anxious (worrying about the health of my elderly parents), and stressed (about the state of my bank account) is grateful for the opportunity to write. And to see what others create in isolation.

Because writing, composing, cooking, designing, drawing, and a myriad of other creative activities are what I see my friends turning to at home. My family members are trying to learn a new language, or a musical instrument, or attempting to navigate online courses. Theatre companies have started live screening their plays. A Vancouver Quarantine Performance Project has been launched. A Social Distancing Festival has been created. People from around the world are singing, teaching, dancing online in an effort to connect to their communities. So, though my artist friends have been left stranded, cancelled, and alone, they have also come together. Culture is what will unite us all through this ominous time.

When Europe—and, sadly familiar, most notably Italy—was devastated by the Black Death between 1348 and 1350, the Renaissance—a period of artistic rebirth—emerged. Artistic projects that often fall by the wayside in our productivity- and finance-fuelled lives may finally be given attention and nurture. Art may actually be created for art’s sake, borne out of catharsis and circumstance and lacking the conventional commercial ambition. And maybe that is precisely what we need. My hope is that performing arts organizations survive to mount them.

Many companies won’t be able to suffer the financial loss caused by the crisis. The Royal Canadian Theatre Company, with whom I have been employed until today, will be losing a great deal of money on the cancellation of Screwball Comedy. As one of many independent theatre companies that receives little public funding, this is dire. As shows around the world close their curtains, please consider donating the price of a ticket to help them survive. We will need them to share our stories written in isolation when all of this is over.

And so, despite the world going screwball, I am trying to smile. If COVID-19 has taught me anything so far, it’s that the performing arts and the artists around the world will always have an integral role to play in connecting people—isolated or not.

Our hope is that when this passes — as it will — we will all be seen as the important component of life and society that we know we are, and that perhaps maybe – just maybe – there might be more support for our work and some funds to replenish our empty coffers.

—Ellie King, Artistic Director of The Royal Canadian Theatre Company

Comments