Slaying the Monster of Stage Fright

The audience goes quiet. It’s time.

I walk out onto the small stage and feel all eyes on me. My legs are trembling. I begin to speak, and almost immediately my tongue goes cold, like it’s covered in ice. And then, suddenly, my mouth goes dry. Like, completely dry. My tongue feels heavy, like it’s an Orca whale I’m attempting to manoeuvre. It’s a monumental effort to pronounce my consonants. Just keep moving your mouth, I say to myself. Don’t stop. My lips are sticking to my teeth.

Time has slowed down. I feel like it’s being marked by a giant sand clock. Each second is a grain of sand dropping painfully slowly into a great heap. My fingers are numb and I’m having a hard time moving them. Only when my character drinks some water and my mouth stops being so dry do I feel my body begin to relax. My tongue shrinks to normal from its whale size.

The show ends, and I’ve survived. But I’m disappointed in myself.

This was last September, on opening night of a new play I had co-created, almost eight years since my last stage performance. When I used to act, nerves were common before a show, but I always felt fine once I stepped on the stage. A former teacher of mine had said, “Nerves are 90 percent creative energy and 10 percent fear of making an ass of yourself. Focus on the 90 percent.” I used to be able to follow that guideline, but, on that opening night last fall, my focus was on the 10 percent.

For the past fifteen years I have been teaching acting and voice. In class we discuss the benefits of breath awareness, and I guide my students through exercises designed to help them experience its fullness and depth, which allows them to find power in their voices. I also teach them how to negotiate their fear as performers.

Though I love teaching, for a while I had been feeling the acting bug nibbling at my heart. But ever since I had stopped performing, my fear of getting back on the boards had been growing. Acting in front of my students, my colleagues, and my community after so many years was a risk. But I could not ignore the feeling. And it felt hypocritical to continue teaching students who battle fear every day if I wasn’t facing my own. I needed to put myself back in their shoes to remember the risk and bravery it takes every time an actor steps on stage.

But on that particular opening night, I hadn’t been able to access any of my teachings. I experienced a classic case of stage fright.

Actors train not to get rid of the fear but to be able to dance with it, because it can never truly be vanquished.

I had barely survived opening night and I had eight more performances to go. Not only did I have my nerves to deal with, but now I had to contend with the fear of the fear. On opening night it had ambushed me like a predatory animal, manifesting as dry mouth that almost prevented me from speaking my lines. I knew it could happen again, that it could strike at any moment, but in what form?

I spent the next day preparing myself psychologically for the performance that evening, visualizing the audience’s eyes on me and practising deep, full breathing. I bought Vaseline to put on my lips to help with my dry mouth, a trick I had been taught in theatre school. I snuck cups of water in strategic places around the set, having figured out where I could make taking a sip look like it was part of the action. I also prepared a secret weapon: a tiny lozenge in the corner of my mouth. I was in warrior mode, ready to tell my demon: “You Shall Not Pass!”

When I stepped out onto the stage for that second performance, my mouth went cold and dry almost immediately. But I was ready. The lozenge began to work and within a few seconds, I felt the saliva flowing. My preparation had paid off. Unlike opening night, I was in control. I continued to prepare in the same way before each performance for the rest of the run, and from then on the show went smoothly.

I don’t know how much the audience noticed my battle on that first night. For many days after, I wished I could erase it from their memory. I wished the audience had seen me at my best, but they hadn’t. I needed to let go of that.

Young actors often think that experienced actors are infallible, that they have perfected their craft and no longer have fear. This couldn’t be further from the truth. I always tell my students that it takes an enormous amount of courage for any actor to step on the stage. Actors train not to get rid of the fear but to be able to dance with it, because it can never truly be vanquished.

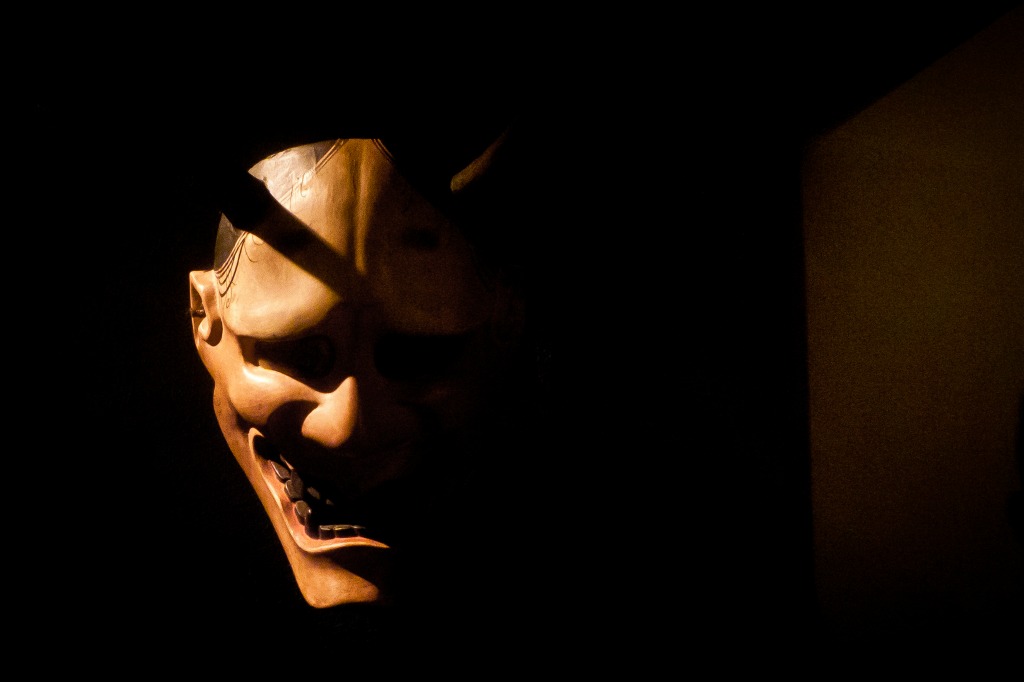

After the show closed, I spent the following few months researching stage fright in order to better understand what had happened to me. I discovered Bella Merlin’s book Facing the Fear, in which she cites Barbra Streisand, Ian Holm, Carly Simon, and Kenneth Branagh, among others, as sufferers. Antony Sher called it “The Fear.” Laurence Olivier called it “a monster which hides in its foul corner without revealing itself, but you know that it is there.” I was reminded that the anxiety of being watched is actually hardwired in our brain: the amygdala, responsible for our survival instincts, senses all those eyes watching us “devouringly” in the dark and triggers our fear. There was something comforting in knowing that I was in the company of others, many of them great actors. I realized that I had faced the monster that resides on every stage.

Management of the fear will only take us so far. We can focus on the 90 percent, we can do deep-breathing exercises, we can visualize the audience. But acting requires a willingness to thrive in the potential for error, to walk on the razorblade edge of total control and total submission. What makes it terrifying is what makes it thrilling. The power of live theatre lies in the infinite possibilities that an actor faces every performance—and their ability to overcome the monster that will always be lurking in the shadowy corner.

Comments