Views from the Stage: It Ironically Looks Like Real Life

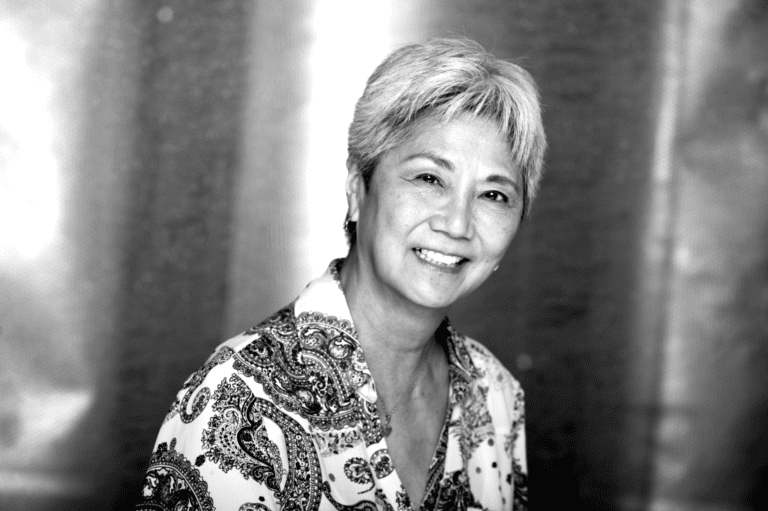

A number of ironies have cropped up over the past number of months for me. Some partly due to the pandemic, and some partly due to other issues, but they all have culminated in my finally entering the lottery for the Toronto Fringe for the first time.

But let me go back in time about fifty years.

I had one of those rare moms who told me I should go to theatre school if I wanted to become an actor. Everyone else’s mom wanted them to go to university or college and get a normal job. Not mine, though.

This was ironic, because back in the late 60s, there was only one school to go to for theatre training, and that was the National Theatre School in Montreal. Period. And no one in the late 60s was going to let some Japanese Canadian kid enter those hallowed white halls.

But that same mom also told me it wasn’t likely that I was going to get roles anyway, for that same reason.

My beginnings as a performer consisted of some television roles wearing the traditional white uniform—nurses, doctors or scientists, or wearing a satin Chinese blouse or speaking with a heavy accent. Didn’t matter that I had no hospital experience, no Chinese garb in my wardrobe, or that I spoke without an accent.

I used to write ironic letters to artistic directors beginning with “do not be alarmed at the face that looks up at you from this picture. I speak English.” I’d have to point that out, even though I’d been born in Toronto to parents who were born in Vancouver.

“Do not be alarmed at the face that looks up at you from this picture. I speak English.”

I dreamed about doing world theatre without worrying whether my appearance would prevent me from ever doing so. My theatre gigs consisted of some nice, if Asian, roles. Rick Shiomi’s ground-breaking Yellow Fever, and the first wife in The King and I, where I got to strut my contralto singing voice, for instance, among others.

But I wasn’t being taken as a regular actor. I was exotic, from somewhere else, specifically of a racial group that wasn’t European. As gratifying as performing a story about the Japanese Canadian Internment could be, I longed to work in classic roles by writers like Chekhov, Ibsen, Coward, Miller, Tennessee Williams—even Neil Simon would’ve done nicely. And because Asian or Japanese was the first descriptive word in a role I played, I never got to get an idea of my strengths as an actor in those world theatre pieces—my niche, my type, my real descriptors. Would I be a better Phoebe or a Cleopatra? Should I investigate Hedda or Nora?

Much of my confusion also came from the number of older roles I played due to the dearth of anyone older than me in my “category.” Both of the above-mentioned roles were older characters.

Let me further illustrate: my first professional gig was in a two-year run of The Primary English Class, which began in a tiny theatre in Toronto. I performed in it across Ontario, across Canada, while it ran concurrently at the Bayview Playhouse and then was remounted at the Bathurst Street Church. During these performances, I alternately played BOTH the young Japanese girl and the elderly Chinese lady.

Such was the reality of my working life. Never been to Japan or China, but what are you to do?

In 1986, Canadian Actors Equity, at their annual meeting, invited me to participate in a break-out session addressing the “problems of the non-white actor in theatre in Canada.”

Problems? Please.

Thus was born the movement toward Non-Traditional Casting: the casting of the best actor for the role without regard to race or ethnic origin, unless it was germane to the play.

Out of this movement came my involvement in advocating for Equitable Participation, or the equitable inclusion of non-mainstream performers in performing arts— a career-long journey for me. It became much bigger than just being about a job for me. I spoke, I wrote, I lobbied. And with my husband, and our theatre company, EMERALD CITY, I even produced a non-traditionally cast production of Private Lives, starring a very black Denis Simpson in the Noel Coward role. I helped organise a symposium, “Talent Over Tradition,” and wrote and lobbied some more.

I achieved a kind of fame for my outspokenness on non-traditional casting. As I say in my Fringe piece, “lots of newspapers talked about it.” In Toronto, the Star, the Globe, and the Sun, as well as the weekly NOW Magazine, covered Private Lives,and most revisited my battle for diversity over the decades – even Hamilton’s Spectator would feature me as an advocate. Canadian Actors’ Equity gave me the Larry McCance Awardfor my work for the underrepresented in the membership.[1]

And things began to change as voices from other communities began to rise. It was gratifying to see people who looked like me, Asian, as well as Black, Latin American, Indigenous, and even Iranian artists telling stories about their worlds, their heritage, their histories, their trials and their communities. Things were beginning to expand, and I marvelled how there were so many voices present—if in theatres run by and for these voices—they were still here. And working. And being heard.

But in the meantime, I was still looking for that part of heaven that said I didn’t need to wait to be cast as an Asian, but just as a person.

And in the meantime, I was joining my third disenfranchised and underemployed group in theatre. First a woman, secondly Asian, and thirdly, a senior.

Which brought me to the final irony in this story of my career.

Shortly after the pandemic shut all theatre down, Act 3, a group of women all over fifty years old, invited me to join them as they gathered to write, read aloud, and act short pieces based on a theme. At first, I was reluctant to join this online group over Zoom, not knowing if I had anything to offer; I don’t write on assignment and have already been dramaturgically involved in dozens of theatre projects over the course of my career. I finally joined the group several months later and while listening, acting in and feeding back on various pieces, I decided to see if there was something in my desk drawer that I might tailor to the theme of this group.

AT THE END OF THE DAY was a play I had originally written for Judith Thompson and the late great Sandi Ross’ SICK COLLECTIVE back in 2000, and when it was not approved for that workshop’s showcase, it was put in a file, and I forgot all about it.

I thought it had possibilities. After I adapted it and included the conventions required of the group’s themes, it was read at one of the bi-weekly meetings and received wonderful feedback. However, it was too long to fit with the parameters of that group—five- to ten-minute pieces—to be able to fit in a show in two acts. I was reluctant to trim it.

And then the Fringe announced its annual lottery.

I have known people to enter the Fringe Lottery for decades and not get a spot. I have never applied for a slot in a Fringe show. I knew the odds of being chosen.

When my name was pulled, I chose to enter AT THE END OF THE DAY.

It needed further adapting—a COVID-19 version demanded the other actors to become “voices,” and the black box in which I imagined the play to be performed became the master bedroom in my house. But at least I had a play. And Brenley Charkow of Bustle of Beast Theatre and Act 3’s dramaturge, who is presently a director at the Shaw Festival, was impressed enough with the writing that she consented to do the play. Bonnie Anderson, an actor who runs Moxie Productions, came on board to film and edit the piece.

To think I hadn’t even wanted to participate in Act 3 to begin with!

So I am amused that the first project I entered into the Toronto Fringe, and the first of my writings to receive production, is a piece about a one hundred year old Japanese woman—my grandmother. What’s this?, you say, you’ve spent all this time offering yourself up for roles that had nothing to do with your racial background and wanting to play your actual age and here you are voluntarily doing the opposite? Yup.

However, this is about family and my personal experience, not a role about someone else’s grandmother. And who better to write about it and perform it? And it certainly is a subject I am familiar with—my family’s history in Canada—the immigrant grandparents, the parents interned during the war, the grandchildren fighting the good fight. Also, I get to play her as myself, with everything I have to bring to the table as an actor. I’m sure my audience will be surprised to know that my grandmother is just like me.

Best of all, it’s not a script that created a stereotype of the Asian woman—the bane of my early film and TV existence—nor is it in another language with subtitles. When I also took into account the treatment of seniors in long-term care facilities during COVID and the abuse of Asians in the news recently, I finally understood the timeliness of my having re-visited this piece for production.

So I offer to tell the truth about my family’s experience while playing a 100-year-old Japanese woman.

It’s all ironic.

[1] Editor’s Note: Kamino additionally received the ACTRA honour of the Lifetime Membership in the weeks preceding this article’s publication.

Comments