A Risk on Paper: Re-writing Theatre at Home

For many of Toronto’s theatres, planning a show online was new territory. For months it was unclear whether theatres would offer digital versions of at least a part of their season or if they would continue to postpone until hosting a live audience was possible again. Now, weeks away from the one-year anniversary of the first time I had ever heard of Zoom, many theatre companies have picked their digital format and stuck to it. While there is still so much left to explore in how we practice theatre online, not every company is following that path.

This year, Toronto theatre company Buddies in Bad Times Theatre’s Rhubarb Festival is taking shape in the form of a book. Bound in bright yellow, the 2021 festival of new works is a physical collection of artists’ responses to how to create liveness for the page ranging from a “choreographic score” to conversations that “look towards the future.” They’re not alone in their desire to move to the page: Theatre New Brunswick is putting theatre in the mail with Post Script, a weekly theatre postcard delivery. Audiences will choose one of three different storylines to follow over a six week period. Although in different provinces, both of these projects were seeded early on in the closures in anticipation of being exactly where we are now.

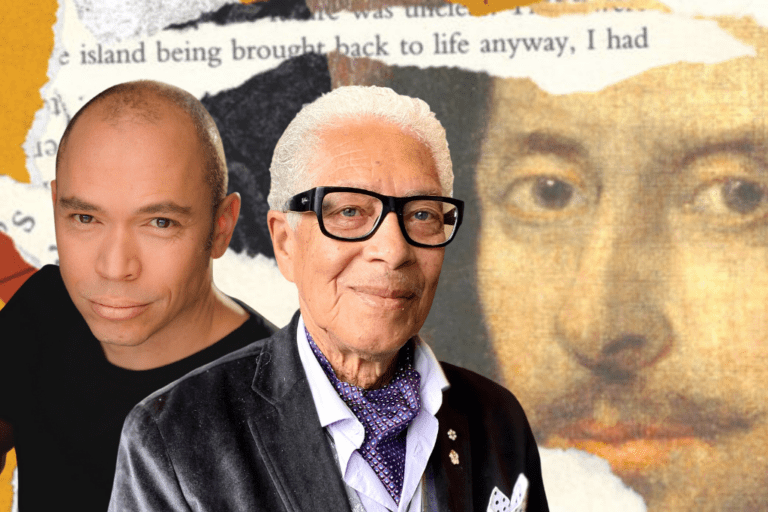

“The germ of the idea came back in April-May of 2020 where we were seeing two things happening: a lot of festivals or theatres that had to close their doors and they immediately transitioned online.” Rhubarb Festival Director Clayton Lee says. “Everyone in March was saying it’s going to be a two-week thing but in my brain I said it’s going to be six months then we’d come out of it in the fall and then come back in the winter, so I didn’t want to necessarily plan for a festival that was going to happen in person and then have to do a quick pivot online. Instead, I wanted to use the time to imagine an alternate version of a festival.”

At the same time last year, Theatre New Brunswick set the first steps for Post Script in motion when they collected letters from the community in a project called Dear Rona. Letters were sent in response to how people were responding to lockdown with the promise that they would be used to inspire future work. Then, Director of Development and Communications, Matt Carter, read about U.K. theatre New Perspectives’ postcard drama, “Love from Cleethorpes,” and the pieces fell into place.

“[Theatre New Brunswick] is one of the oldest regionals in the country. We’ve been mandated to tour the province since day one. The company always thinks, How do we get beyond the immediate city?” Artistic Director Natasha MacLellan tells me. “A lot of our audience isn’t the type to necessarily be intrigued by digital.”

When purchasing a ‘ticket’ to the Rhubarb Festival or Post Script, audiences should not expect to see a traditional script. This is not the blueprint for something else to come, but rather, as MacLellan puts it: “This is the show.”

“The story was submitted to us anonymously when we did our Dear Rona call a year ago; then we had a playwright take that story and format it the postcard and divide it into chapters,” says MacLellan. “I was thinking the other day, who’s the actor in this scenario? Who’s the audience? Who’s the storyteller? But it’s all combined. The person who gets the card is the actor but they’re also the audience.

“Are people going to read it walking into their house from the mailbox or are they going to sit down with a cup of tea and read it?” She continues, “I don’t know. They’re going to decide it all which is really cool to think about.”

On the other hand, the Rhubarb Festival leaves less room for interpretation.

“These projects were designed for the page vs. the script. They’ve all been individually and collectively conceived in this way. I don’t think the audience can go into it imagining that this is what they would see in a normal Rhubarb year but just transposed onto the page.” Clayton Lee says. “Most of these projects won’t be able to exist in any other context, in the Zoom world or post-pandemic theatre but instead they’re an opportunity for the artist to try something out.”

Providing the audience with a concrete, unchangeable item not only changes how we view the work but how the show will be remembered. It can always be revisited as long as you have the book or the cards. Although this gives away some of the work’s impermanence, its etherealness (or perhaps exclusivity) is not entirely lost: the Rhubarb Festival only has 888 ‘tickets’ available, while Post Script has 100.

Lee explains, “The rationale behind that is to attempt to mimic the experience of live performance as much as possible. Once these copies are out in the world they’re gone. The individual people who purchase a copy will have it to refer to but it won’t be as widely received as a normal Rhubarb Festival or any kind of recordings.”

While this sort of limited archiving was not an explicit goal for either Theatre New Brunswick or the Rhubarb Festival, it certainly contributes to both companies’ desires to change our relationship to theatre.

“What it felt like [when theatres first closed] is we’re doing the status quo by putting it online, putting it on Zoom, or putting it on Youtube, or whatever. It felt like there was a real missed opportunity to really go into the heart of the work that we do and seeing how we can improve it or make it better, whatever that means.” Lee says, “In my second year with Rhubarb, my overarching ambition for the festival is bringing it back to a space of experimentation.”

For MacLellan, experimenting is “reconnecting us to that moment of joy that the theatre can bring us—the encountering of the unexpected.

“I’ve been making theatre here for close to 20 years. I was doing a lot of things on autopilot and the scary thing about last year is that there’s been no autopilot. Every day’s different so you get an idea and you just invent it and you go for it and I’ve really enjoyed that feeling. It feels like theatre did when I first discovered it.”

Companies are being forced to work with processes that haven’t fully matured in a way that hasn’t been seen a while. Instead of working with fully outfitted venues, companies have had to figure out new platforms, the logistics of collaborating while socially distanced, and how to engage audiences through it all. In the pre-pandemic world, we might have had harsher expectations for what theatre should look like and how a season would be planned; but now, much of that has been thrown out the window and not everyone has taken advantage of the opportunity to take risks.

“A lot of my colleagues aren’t trying anything and I really wish they would because it’s the perfect time to try something.” MacLellan says, “It’s the perfect time to take a risk.” And she’s right.

In this time where no one knows what to expect, every show is a chance to experiment, reject our normal, and continue to find new paths of connection.

Comments