For Daniel MacIvor, the best theatre ‘honours and interrogates’ the moment

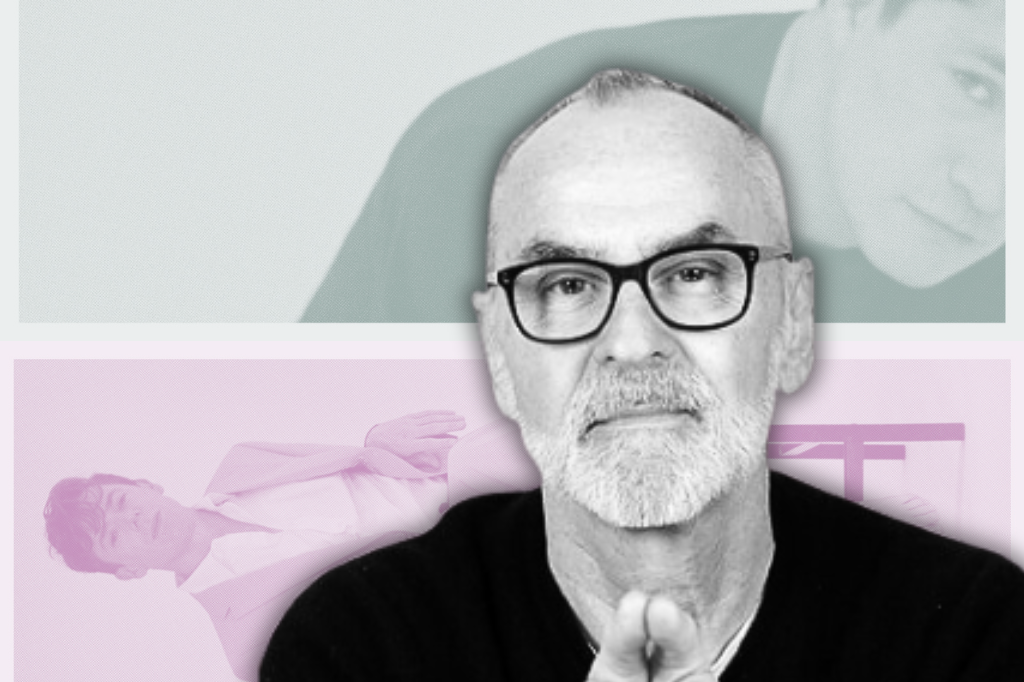

If you have strong opinions on Canadian solo performance, Daniel MacIvor may be to blame.

Born in 1962, the Nova Scotian boasts a laundry list of awards for theatre-making, from the Governor General’s Award for Drama to the Siminovitch Prize, not to mention a GLAAD Award, a Village Voice Obie Award, and any number of other laurels. MacIvor is a king, Canadian solo performance his kingdom — his monologues developed with longtime collaborator Daniel Brooks live on as some of the most important in the genre, with such hits as House, Here Lies Henry, and Monster.

The latter two return to Factory Theatre as a double bill this winter, directed by Tawiah M’Carthy and Soheil Parsa and starring Karl Ang and Damien Atkins. While MacIvor might not be as involved in Here Lies Henry and Monster as he was during their runs in 2006 and 2007, he’s still very much in the picture, offering guidance and “mini-workshops” to the plays’ contemporary creative teams.

“I went through the text with them, and I spent time with Karl and Damien independently,” he said in an interview with Intermission. “I did rewrites on both of the scripts based on what we wanted the shows not to be — we decided we wanted them to be current, and not so much of a [past] moment.”

The notion of evil is a very different conversation today. In some ways, I think that seems to be more and more located in a sociological or geopolitical kind of vibration. But then, in one-on-one situations, we’ve become so much more tender.

The world has unarguably changed since the plays’ first outings, says MacIvor, a difference he says has marked conversations about updating them. “The world has become both more tender, and more brutal,” he said. “The notion of evil is a very different conversation today. In some ways, I think that seems to be more and more located in a sociological or geopolitical kind of vibration. But then, in one-on-one situations, we’ve become so much more tender.”

Here Lies Henry and Monster form a diptych of the human psyche, best seen together but still complete works of theatre of their own. Here Lies Henry explores the idea of untruth, offering audiences a life story through the lens of a self-proclaimed liar, while Monster drills through the layers of 16 different characters to find the truth of an individual experience. The plays talk to each other — about truth, fear, and the vast experience that is personhood — and reveal MacIvor’s fascination with selfhood.

“It’s as if you’re looking at the same play in two different ways,” he said of the relatedness between Monster and Here Lies Henry. “Daniel and I endlessly had this conversation about this kind of performance, which he always defined as ‘an explosion of self.’ There’s the self that’s always going to be there…when I performed this work, it was very sincere, but it was only because that was my vulnerable default as a performer, to go to that particular place. So whatever your vulnerable default is as a performer, you go there.”

MacIvor, ever a fan of metaphors, says the plays gesture toward the idea that performance is a sort of biography, or a conjuring, or a map. “These plays aren’t about ideas,” he said. “It’s not a bunch of ideas. Sure, there’s ideas in it. But there was never a conversation about, ‘let’s make a play about this idea.’ It was about, ‘let’s make space for performance to inhabit, that will transform energy.’ And that’s what both of them do, or aspire to do.

“These performers will make this work their own,” he continued. “The plays belong to them now. They both vibrate on such beautiful high levels. They will own it, they will take it, they will invest themselves in the way they need to. I don’t think the plays work if they’re treated like a text. The text is just a tool towards manifesting energy in a room with people.”

Brooks passed away on May 22 of this year, a fierce blow to the Canadian theatre community. Prior to his death, he performed his solo Other People at Canadian Stage to much acclaim, with dramaturgy by MacIvor. When reflecting on the work of the Daniels of Canadian theatre, it’s difficult to pick their careers apart — for so long, they’ve been interwoven in shared projects and philosophies.

That’s the hope. We’re expressing the hope by continuing to work. And I guess that’s partly why I feel like I want to keep doing it. I need to carry that part on.

“We were just doing the work,” said MacIvor. “Daniel didn’t really care what I talked about as long as I told the truth. He didn’t care what I invented as long as I was telling the truth. More and more without him, my responsibility is to step even further into telling truth, so I can bring the truth of myself, or whatever the hell that is, and whatever the fuck that means.

“People would always say to us, ‘there’s no hope in it’ about the work,” he continued. “But Daniel would say, the ‘hope is that we’re doing the work.’ That’s the hope. We’re expressing the hope by continuing to work. And I guess that’s partly why I feel like I want to keep doing it. I need to carry that part on.”

Towards the end of our interview, MacIvor returned to his musings on ideas — and that the best plays, in his opinion, aren’t merely about them, but about the human experiences and psyches that contextualize them.

“Of course, it’s all ideas,” he said. “Ultimately, that’s everything, right? But I’m not interested in trying to sell you my idea or convince you of my idea. I’m interested in how to elevate, and how to share an action, and how to honour and interrogate the moment.”

Monster and Here Lies Henry open at Factory Theatre on November 16 and November 23, respectively. More information about the production is available here.

Comments