First Jobs, Worst Jobs, and The Flick

For most Canadian artists, a side hustle is a fact of life. Despite endless hours dedicated to the craft, your work almost certainly doesn’t pay the bills. Waiting tables is (of course) one of the more common options, particularly among actors who need their daytimes free for auditioning and (occasionally) acting. But the realities of the sector mean that folks often use a significant portion of their creative energy finding ways to make money. (My past gigs include telephone psychic, porn website editor, and selling exorbitantly-priced purebred dogs to wealthy middle-aged women.)

The characters in The Flick don’t seem to have artistic aspirations. But whatever they want to be doing, it’s clearly something other than working in a derelict movie theatre. Unfolding over nearly three hours, Annie Baker’s 2013 gem follows three employees of a failing cinema as they mop floors, collect trash, and chat about their lives. Hailed by New York Times critic Charles Isherwood as “naturalism on steroids,” the play garnered an Obie Award, a Pulitzer, and launched Baker into the theatrical stratosphere. Two years after smash hit Toronto productions of Baker’s The Aliens (Coal Mine Theatre, helmed by Flick director Mitchell Cushman) and John (The Company Theatre’s Dora-nominated run), The Flick (Outside the March and Crow’s Theatre) is one of 2019’s most hotly anticipated theatrical events.

Since her career explosion, side jobs are a thing of the past for Baker, something she laments in a conversation with actor and director Greta Gerwig for Interview. Beyond making money, her side gigs (which have included wrangling contestants on The Bachelor, researching questions for Who Wants to be a Millionaire?, and, yes, waiting tables) provided critical fodder for her writing.

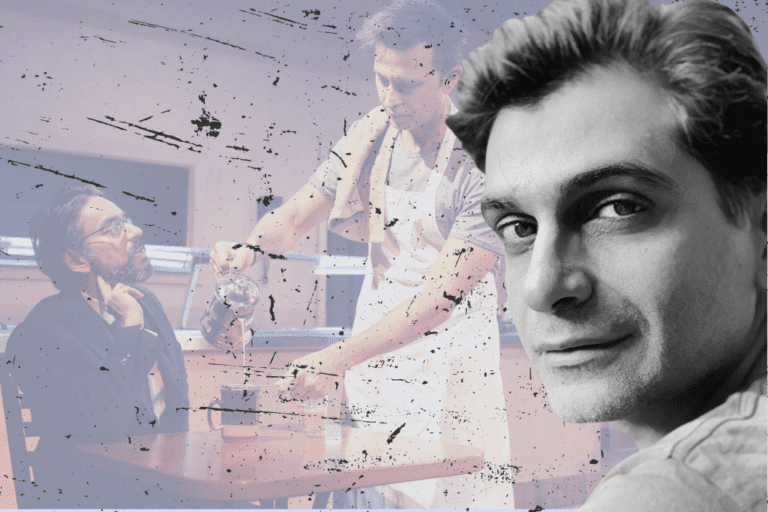

Colin Doyle, Durae McFarlane, and Amy Keating in The Flick. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

For the cast of The Flick, however, past jobs have more often been sites of suffering than sources of inspiration.

Durae McFarlane (who plays Avery) recently returned to Toronto after graduating from the University of Windsor. While still in high school, he landed his worst and shortest gig, working for a lawn aeration company. McFarlane admits that the fact there was no interview should have tipped him off. But the training process was sufficiently convincing that he thought he’d give it a shot. The workday consisted of a 7am pick-up and then being dropped off in a residential area where the crew were instructed to go door to door, hocking their services to suburban homeowners. The pay was commission only (next to nothing) and he wisely threw in the towel after only two days.

Colin Doyle (Sam) fills the gaps between shows with a variety of arts-related jobs, mostly producing and box office gigs. His work history leaves him surprisingly well prepared for The Flick, having spent his twenties working in two different cinemas. Like McFarlane, he sank to the depths of employment hell as a teen, when he was a dish pig at a Scarborough yacht club. A friend tipped him off to the job, but failed to mention some of the hazards.

“You were burning yourself on scalding hot water, trying to get the dishes clean and back in circulation,” Doyle says. “And the chefs would get drunk and throw knives at you as the night went on.”

His worst night on the job was also his last. It was the club’s weekly Wing Night (ten for a buck!) and the chef had forgotten to fish them out of the deep freeze. Doyle was plucked from the dish pit and asked to chip them out of a block of ice. He was canned for cutting himself and bleeding all over the frozen poultry, and then had to do a lonely hours-long walk of shame home. Adding insult to injury, his last cheque bounced.

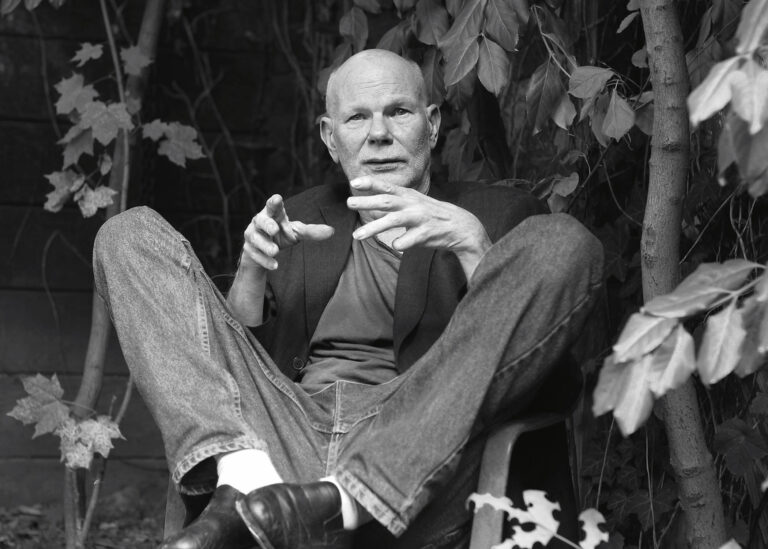

Colin Doyle in The Flick. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

Amy Keating (Rose) loves her current job at an artisanal chocolate shop—no surprise, since her past gigs have included hocking newspapers at a subway station and enticing passersby into a flower shop while dressed as a clown. Like Doyle, she worked at a cinema (Edmonton’s 100 year old Princess Theatre). She also did five years at her local video store, a position she remembers fondly, with the exception of a horror film-inflected phone call from a heavy breather, asking about their “adult” film section. Unaware of the terminology, Keating cheerfully replied that they stocked a wide range of R-rated flicks. When he pressed more specifically about their pornographic selections, she got wise and hung up.

Brendan McMurtry-Howlett (who does double duty as Skylar and The Dreaming Man) is lucky to make the bulk of his living through theatre (both performing and teaching), with the occasional smattering of tech calls. His pinnacle of employment anguish was the summer he spent hawking ice cream at Baskin Robbins.

“Some flavours were harder to scoop than others and my heart would sink when anyone ordered Chocolate Peanut Butter,” he recalls. “On long summer afternoons my wrists would be giving out by the end of the shift.”

Aside from the overly corporate atmosphere (each scoop had to be weighed to make sure it wasn’t too large), the manager refused to offer the staff any free product. As a final act of retaliation, McMurtry-Howlett surreptitiously swiped a takeaway container of Gold Medal Ribbon on his last shift, but then spent the next week petrified that police would show up at his door.

Amy Keating in The Flick. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

The fact that most artists in Canada require a second job isn’t a secret. When discussing our work during cocktail parties, family reunions, or first dates, we’ve all had the experience of being asked, “But what do you really do?” While arts organizations like to tout surveys showing widespread public participation in the arts and support for arts funding, when it comes to securing additional funds for our industry, politicians tend to shrug and look the other way.

In contrast, several European countries including France, Belgium, and most of Scandinavia, consider artists to be public sector workers, offering various forms of guaranteed income (usually in the range of $1500-2500/month), which they consider critical to an industry where work will always be uncertain. This makes the arts a more viable career, and helps stem the flow of talent we commonly see in Canada, as inspired young creators come face to face with the hard realities of the business and quit their craft only a few years after graduating. Until we effectively make the case for our industry to be properly subsidized the way many others are (What’s up Big Oil?), we’ll have to be content with using a significant chunk of our creativity finding ways to get by.

The Flick runs Oct. 6 – 27 at Streetcar Crowsnest in the Guloien Theatre. Tickets and information can be found here.

Comments