History Reimagined Onstage in The Royale

On May 24, 2018, Donald Trump issued a posthumous pardon for Jack Johnson, the first African-American to win the world heavyweight champion title in 1910. Three years after his win, Johnson was arrested for crossing state lines with a white woman and served time in prison. His pardon, over a century after his arrest, was spurred by a celebrity-driven campaign led by Sylvester Stallone. When the news broke, CNN ran the headline: “Who was Jack Johnson, the boxer who Trump posthumously pardoned?”

Despite having made history in his sport, Johnson’s name was not widely recognized across America. But his tenacity, grit, and ambition inspired playwright Marco Ramirez to pen The Royale, a fictionalized telling of Johnson’s story that has its Canadian premiere at Soulpepper as part of their 2018/2019 season.

Plays based on marginalized historical figures offer new perspectives and insight into stories that have often been forgotten, sometimes even inspiring audiences, or readers, to seek out more information about the people who had a lasting impact on the world as we know it.

Johnson was born in the late nineteenth century in Galveston, Texas, just as Jim Crow laws—which were in effect from 1877 to 1964—spread across the United States and institutionalized innumerable disadvantages for Black Americans. Johnson took to boxing at an early age, lifting weights and punching the bag at a local gym where he worked as a janitor. His first professional fight, in 1898, was a knockout. Just over ten years later, undefeated world heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement to fight Johnson for the heavyweight title. What then became known as “the fight of the century”—which now commonly refers to the 1971 match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier—saw Johnson defeat Jeffries in front of more than twenty-five thousand spectators.

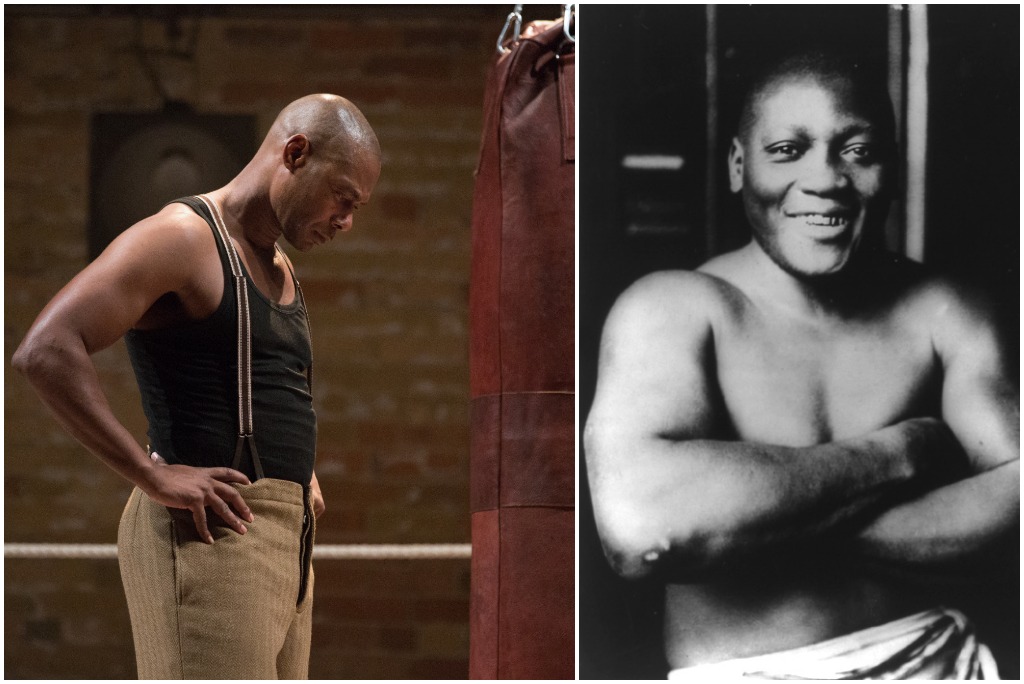

Former boxer John L. Sullivan introducing heavyweight champion of the world Jack Johnson, moments before the latter’s fight against the returning champion James J. Jeffries. Photo taken on July 4, 1910.

Johnson’s victory threatened white supremacy. Riots erupted in New Orleans, Houston, New York, Los Angeles, and other cities. Black people across the country were harassed, assaulted, and murdered. The records show that between eleven and sixteen people were killed, though there were hundreds of victims in the aftermath of the fight. The government repressed all footage of the fight and news outlets misreported the match in an attempt to whitewash the outcome.

This landmark fight broke the racial divide in boxing. Ramirez, who had been drawn to the challenge of putting boxing onstage, knew this was the story he wanted to make into a play. Feeling like Johnson’s victory was well-trodden territory and wanting to reveal a nuanced portrayal of a man behind his gloves, Ramirez moved beyond the facts available to him and took many liberties with the script. Jack Johnson became Jay Jackson, and Ramirez ensured Jackson’s name was repeatedly spoken to remind the audience of the fiction onstage.

For Canadian actor Dion Johnstone, who plays Jackson in the Soulpepper production, the process of discovering the real history behind the script was a powerful experience. “[Johnson’s] not a figure or a hero who would normally be put on stage,” he says. “He was an anti-hero, a gifted, exceptional athlete who was given the opportunity to fight against the reigning world champ.”

Johnstone shared how Booker T. Washington, a prominent African-American leader at the time, wanted Johnson to consider how he presented himself publicly and how his behaviour reflected negatively on the Black community. Johnson was known as a “sport”: someone who loved to gamble, drive fast cars, date women (including white women), and, “by anyone’s definition, live his own life,” Johnstone says. Ramirez’s script takes the mythic significance of a boxer and distills it into an intensely personal story. The play guides its audience through the lead-up to the most important moment of a person’s life, and the toll of that pressure on a human being.

Christef Desir, Diego Matamoros, and Dion Johnstone. Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann.

Ramirez emphasizes that Jackson is driven to be the best at his sport, like any other athlete. But he knows what the backlash would be if a Black man won a world boxing title. This inner turmoil resonated deeply with Johnstone: “It matters for a new generation to see that they are beautiful and can achieve greatness.”

Born in Montreal and raised in Alberta, Johnstone didn’t see himself reflected onstage or onscreen, especially in classical work, growing up: “I had to fight to tell myself I could do this, I could go for leading roles. I kept bolstering myself up because it really means something. Audiences, people of colour, can see themselves represented on stage and see that they are already part of a legacy.”

Earlier in 2018, Johnstone played the role of Ira Aldridge in Chicago Shakespeare Theatre’s production of Red Velvet by Lolita Chakrabarti. American-born Aldridge was the first Black actor to play Othello, in a production that took place in London’s docklands in 1825 to vehement protest. Despite aggressive and persistent racism, Aldridge achieved a highly successful career. Before taking on the role, Johnstone didn’t know of Aldridge’s legacy—it’s there if you know where to look, but Johnstone noted that Aldridge is not celebrated the way David Garrick is. “What might my life have been like,” Johnstone questions, referring to his own acting path, “if I knew there was someone’s shoulders I could stand on?”

It matters for a new generation to see that they are beautiful and can achieve greatness

Considering that North American history has been written from a Eurocentric, cisgender, heterosexual, colonial viewpoint, stories that do not fit into this narrative are often lost. Racialized communities—as with many other oppressed groups—have to fight for the stories of their ancestors to be upheld and celebrated. Theatre is a medium for audiences to actively engage with the lives of these individuals. Historical fiction allows playwrights and audiences alike the freedom to imagine the struggles, sorrows, and victories of the people who came before us and to move beyond the constraint of fact.

Plays like The Royale and Red Velvet offer more than entertainment or education: they actively fight cultural erasure. Theatre that fictionalizes history allows us to connect on a deeper level with our personal stories. Plays like these ask us to question our worldview and show us another side of the history. They explore the humanity in figures who have been forgotten, celebrated, or placed on pedestals. And they emphasize that what’s happened in the past can have a lasting effect on the present.

Comments