Sitting in the Dark

In a stiflingly hot elementary school gym last year, I saw one of the most engaging shows I’d seen in a long time. There were beautiful songs, epic speeches, and audience participation throughout. The show lasted over four hours, and most of the audience members were, at some point, moved to tears. Entry had been free, although I did have to wake up early on a Sunday. This particular “show” was a church service, and it was among the most spectacular and bizarre theatre I’ve ever seen.

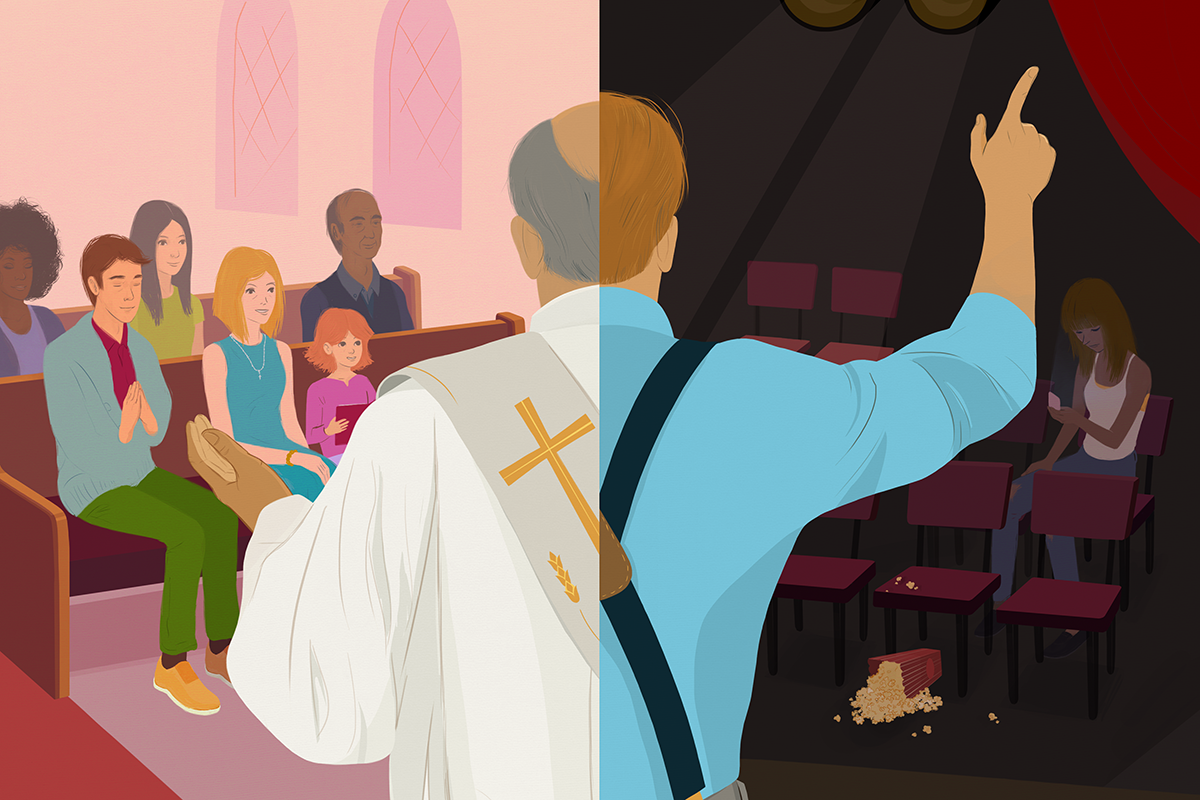

On the surface, contemporary theatre and religious institutions occupy very different places in our society. They seem diametrically opposed in terms of their respective messages: generally, theatre as a bastion of liberalism and progressive ideals, and the church (or mosque, synagogue, temple, etc.) traditionally advocating for conservative values. Yet there is one way that these two old-as-civilization-itself institutions are similar: they both face problems in appealing to young adults. Statistics Canada 2011 shows a general decline in both religious affiliation and attendance, with millennials leading the charge as the fastest growing apostate group. And people 25–34 are also among the least likely to go to the theatre, according to a 2010 Canada Council report. Whatever the message, it will fall on deaf and absent ears as far as young people are concerned.

I’m certainly not the first to consider parallels between these two cultural phenomena, nor to lament the decline of interest in theatre. In 1888, August Strindberg claimed that “… the theatre, like religion, is dying out, a form for whose enjoyment we lack the necessary preconditions.”[1] So, just what are those “preconditions” that make for a theatre-loving (or church-going) community? Especially for the younger generation? Can theatre and religion find any common solutions to their marketing conundrums? Should they change to fit the current preconditions of society, or demand that their patrons conform to traditions and customs established when society’s preconditions were very different?

Full disclosure: I fall squarely in the age demographic that both religious institutions and the theatre need to attract. I’m an atheist theatre school graduate, raised by secular Jewish theatre artists, so my perspective on this issue is certainly skewed in one direction. However, like many atheists, I am fascinated by religion and its influence on both society and individuals. And I have a lifelong love-hate relationship with Toronto theatre. Having recently returned from a long acting hiatus and a brief foray into the corporate world in China, these thoughts and questions were inspired by the arrival of a new church in my neighbourhood of Kensington Market.

The pamphlet showed a young contemporary James Dean–style figure, leaning on a wall in a cool, loitering pose next to an electric guitar. It read: “Christ Embassy Church: God believes in YOU!” This piqued my interest and got me thinking about the connection between the church and the theatre in terms of their youth outreach, and I decided to go to the opening service to check it out. The similarities to theatrical performance were evident as soon as I sat down: musicians fussed with their instruments and made sure their blocking was open to the audience, while the pastor, a large Greek woman, seemed to be doing vocal warm-ups while fixing her hair. The less obvious resemblances were there too: community members happy to see one another, dressed up, chatting, and excited for the show. One stark difference that struck me was the diversity of the attendees. The ages ranged from infants with their young mothers to elderly couples. I heard conversations in French, Spanish, and a Slavic-sounding language I couldn’t identify. Just after the service started, a group of 15–20 year olds walked in, many wearing shorts, fitted hats, and headphones, who seemed to represent almost every ethnic group found across Toronto. The older churchgoers at the front smiled at them, and one immaculately attired woman dug out some extra plastic chairs to accommodate them. My first thought was: this is the kind of audience that most downtown theatres could only dream of attracting with any consistency.

Once the service started, however, it was clear that underneath the friendly exterior there lay a certain foundation of exclusion. References to HIV, drug addiction, and depression seemed to be a leitmotif of the sermon, dismissed as afflictions only suffered by those who did not live in Zoe, a Greek word ostensibly meaning “a life lived with and for God.” During these moments, a tearful elderly woman sat clutching her four-legged cane as those around her stood. Whether the tears were of faith, physical pain, sadness, or ecstasy, I couldn’t tell. The folks at the service were moved to speak in tongues, and call out praises to God, and raise their arms heavenward almost mechanically every few minutes. When the band sang, so did nearly everyone else. (I was actually quite impressed at the harmonizing skills of my immediate neighbours.) I had certainly not seen an audience so moved by any theatrical performance in a long while.

The pamphlet showed a young contemporary James Dean–style figure, leaning on a wall in a cool, loitering pose next to an electric guitar. It read: “Christ Embassy Church: God believes in YOU!”

It also invited (and in some cases demanded) active participation by the audience. After the service, which lasted over three and a half hours, the pastor beckoned me over, introducing herself as Taba. Earlier during the service, she had quite literally dragged me to the front to be saved by Christ, and I, along with several others, had stood in front of the congregation as they reached their arms towards us and prayed for our souls. One young woman had burst into tears at this moment, as did her friend watching the salvation from the front row. I think Pastor Taba could tell from my face that I had not truly accepted Jesus Christ into my life. When she asked me, I confessed that no, I had not. When I told her I was there in the spirit of enquiry, writing about the church and the theatre and their respective appeal to the future generation, she gave me her number and told me to call her later that night. I did so a few times, but with no response.

My experience in that particular church is not representative of religion as a whole, I realize. But I felt both engaged and alienated as a first-time, outsider audience member, and there occurred to me several takeaways for theatre companies. The pros of that kind of a service were the active encouragement of participation, whether joining in with songs or giving vocal response to the pastor’s sermon, which enhanced the theatrical elements, as well as the fostering of a sense of community. Young people from diverse backgrounds were welcomed with open arms and seemed to be central to the form of the enterprise. However, the assumptions underlying the content were disconcerting. The judgement and derision towards addicts and the mentally ill made me feel alienated for having a different view, and given that the pastor seemed to be unwilling to speak to me once she realized I was not a believer, we missed out on any true discussion. To be honest, I’ve sometimes felt this in the theatre too, that you have to be a member of the club to truly enjoy a show. Or, to put it another way, that there exists an artistic language that some performers speak, as though they do not want outsiders to understand, and jokes are told with an assumption that every member of the audience has a certain sense of humour or politic. This may be a reason why young people who have no connection to the arts may avoid theatre as an entertainment option, which is a sentiment I’ve heard from many of my non-theatre friends when they’ve come to see performances of mine or of others’.

However, I’ve been out of the scene a long time. To get a better sense of the current state of Toronto theatre from people more closely involved, I talked to both a critic and a young artistic director of a not-for profit theatre company. According to J. Kelly Nestruck, theatre critic for the Globe and Mail, contemporary theatre in Toronto “tends to be very Protestant… people sit in the dark, quietly, and just listen.” He suggests the decline in interest among young people in Toronto for both church and theatre may be partly due to “the fact that we’re just not used to sitting like that anymore.” Educational research shows that encouraging movement among children when they need to walk around improves attention and engagement—teachers are beginning to subscribe to the “ditch the desks” theory of classroom configuration and activities. Perhaps this would work for these same kids as they grow into potential theatre patrons and congregations, creating a more relaxed atmosphere in which those who want to stand up and move around, or even engage with the performers, can do so without being reprimanded.

Just such an opportunity came my way when I saw DLT’s Off Limits Zone during the Luminato Festival. The company calls the concept “audience-specific” theatre, meaning one audience member per show. The ticket-holder receives instructions after purchasing their ticket, informing them when and where to show up. Among various random passersby, a stranger approaches you, and the play begins, with you as its protagonist. What follows will be slightly different each time, depending on the participant and their reactions to the characters they meet, but it was one of the most engaging theatrical performances I’ve ever been a part of.

I don’t think I’ve seen a play in quite some time where my attention didn’t wander at least for a few seconds here and there, but during this show I was unable to disengage. This was in many respects due to the novelty and the audience-specific format of the show, to be sure, and some might argue that this type of theatre is an unsustainable business model, but that way of thinking might be somewhat behind the times.

Over the past two decades, much has been made by economists of the transition in first-world societies from an information economy, where knowledge is the most scarce and therefore most precious resource, to an attention economy. My experience at Off Limits Zone, as well as the Christ Embassy Church, made me think about the two-way nature of attention. As Michael H. Goldhaber writes in a seminal article on this topic, “Whenever you pay attention to (someone or some performance), you have to be getting at least some illusory attention back.” The obvious care and devotion on the part of the performers of Off Limits Zone to keep me involved made me feel really appreciative, and I found myself thinking about the experience many times in the weeks after. Theatre companies understand that their marketing must adapt to the times by establishing a social media presence, but why not adapt the format and content of the product itself, encouraging more audience participation in new and unconventional ways?

Certainly one thing religion can offer society, as I experienced first-hand at the Christ Embassy service, is the sense of community it engenders. Theatres in our fair 6ix could do well to emulate this sort of outreach.

When the audience is also the protagonist, you have the immediate opportunity to say what you think, and disagree with the script, which brings me back to the question of dissenting voices in an audience, whether church or theatre. On this topic, Nestruck told me about Daniel Karasik’s blog Thoughts from a Glass House, suggesting that at one point it had gone off the rails when Karasik tried to tackle the subject of the glut of whiteness in Toronto theatre and was called to task for “being another white guy blathering on.” I read his blog and found at least the explanation for its existence refreshing, distilled nicely in this sentence: “Why can’t we call bullshit more often, not only at the bar but also in public, when our theatre doesn’t ask smart enough, urgent enough questions or do so in complex enough terms?”

In my experience, this is very difficult in the theatre community. There seems to exist an understandable but perhaps unhelpful aversion to criticism from all sides: unimpressed theatre reviewers are often dismissed as ignorant, and non-artist audience members who didn’t like or “get” our shows even more so. As for our peers in the industry, I have rarely if ever felt comfortable expressing my honest opinion about a friend or family member’s show if it’s not a rave review. The few times I’ve tried, with people close to me, have not ended well. Now, this may not be the experience of everyone in the community. But in the age of Yelp, peer-to-peer services like Airbnb, and social media outlets like Twitter, one thing the market has made clear is that young people like expressing their opinions, especially about the products they consume. I think they have reason to believe that they would not be welcome in the theatre community, and maybe it’s up to us as theatre professionals to lead by example and start voicing our opinions honestly, responsibly, and publicly. I realize that’s a tricky proposition, but the stakes are pretty low for us as theatre artists in Toronto. Dissidents in theocracies like Saudi Arabia are regularly flogged, jailed, and even killed for expressing their opinions; surely we can channel a fraction of their bravery by being honest with each other, and thus improve our community and celebrate the freedom we enjoy here.

But does that sort of conversation require feeling part of a given community to begin with, whether theatrical or religious? Certainly one thing religion can offer society, as I experienced first-hand at the Christ Embassy service, is the sense of community it engenders. Theatres in our fair 6ix could do well to emulate this sort of outreach. One theatre that seems to be doing exactly that is b current, run by artistic director and actor Jajube Mandiela who is the daughter of its founder, ahdri zhina mandiela.

Originally founded as a space for black theatre artists to develop their craft and present new works, the company has now “grown to support work from all diasporas.” By being clear in their vision, Mandiela says, “The kids from these communities, often from low-income families, the children of immigrants, or immigrants themselves… see artists and stories that reflect them and interest them.” b current aims to be part of their community and their regular life, and make them feel like they belong when they come to a show, whether dressed in “pyjamas or a nice suit, whatever [they] want!” This echoed something Nestruck told me when I asked him how he got into theatre: he said his first great experiences at the theatre were as a teenager, seeing free shows while volunteering at the Montreal and Winnipeg Fringe festivals. “Seeing other young people in shorts hanging out… I would never have bought a ticket to [Montreal’s prestigious] Centaur [Theatre], it just didn’t feel accessible.”

Mandiela and I talked about this feeling of belonging, and I told her about what I saw at the Christ Embassy Church, how included the young, casually dressed kids were made to feel. And although the numbers show religious affiliation dropping sharply among Canadians born in this country, the numbers stay static among immigrants. Conversely, Canadians who self-identified as a member of a visible minority group are less likely than those who are not members of a visible minority group to attend theatre performances, similar to first-generation immigrants versus non-immigrants. Could this be said to mean that immigrants and members of minority groups are more likely to choose a place of worship over a place of artship (is that a word? it should be) as their community centre? “Probably because the stories and faces don’t represent them at the theatre,” Mandiela says, “and they don’t feel like they belong.”

I know I’m probably preaching to the choir here. And I’m half an outsider myself, someone who grew up in this crazy community and then ran away for a while. But I think that’s the biggest takeaway for me from this white-guy-blathering-on about the parallels of church and theatre: religion is, at its best, a place where people from any background, and any tax bracket, can come and feel a sense of togetherness and think about the big questions: love, hate, kindness, cruelty, tolerance, bigotry, and the struggle between good and evil that exists inside each and every human being. The stories speak to you, whoever you are, and those around you make you feel like you belong. Certainly enough to tolerate a dissenting voice or two. And hopefully, though maybe not every time, it can move you, to tears or to laughter, and every once in a while provide you with an unforgettable, transcendent experience that just can’t be found anywhere else. Sounds like a good metric for the theatre to me.

[1] From author’s preface to Miss Julie in Strindberg: Five Plays, translated by Harry G. Carlson, University of California Press

Comments