Truth, Survival & Creation: In Conversation with Sizwe Banzi is Dead ’s Amaka Umeh and Mumbi Tindyebwa Otu

Sizwe Banzi may be dead.

But the production’s spirit is more alive than ever with a new run at Soulpepper Theatre, almost 51 years after its South African premiere at Rhodes University.

Written by the critically and culturally-acclaimed playwright Athol Fugard, Sizwe Banzi Is Dead is not only a comedic performance piece of dual identities, but a crucial piece of protest art that reshaped audiences worldwide.

“I was trying to remember … the recorded performances of [Sizwe Banzi] by the original creators because it was created as a divisive piece with two performers, John Kani and Winston Ntshona. They were baring so much from their own lives [and] their communities, and it was dangerous [because] it wasn’t even legal,” said Mumbi Tindyebwa Otu, director of the Soulpepper production, in an interview.

“There was such urgency … to tell the story, and that really drew me to it,” said Otu. “The fact that it was so necessary and so dangerous, but it was the only choice [for] artists — to create.” Born and raised in Kenya, Otu strongly identified with the theme of survival displayed throughout the play both as an African and as an immigrant.

Under apartheid, laws were passed to ensure that Black South Africans carried identification on them at all times. This would restrict their movement around the country, even where they lived, which was sometimes at their place of employment.

“Those [themes of survival] definitely resonate in terms of thinking of my community and lots of stories of people I know,” she said. “In an African context, [I was just] thinking about documentation and what you need to be able to live in [Canada] … and who gets to stay here and the privilege of not having to struggle with those kinds of documents.”

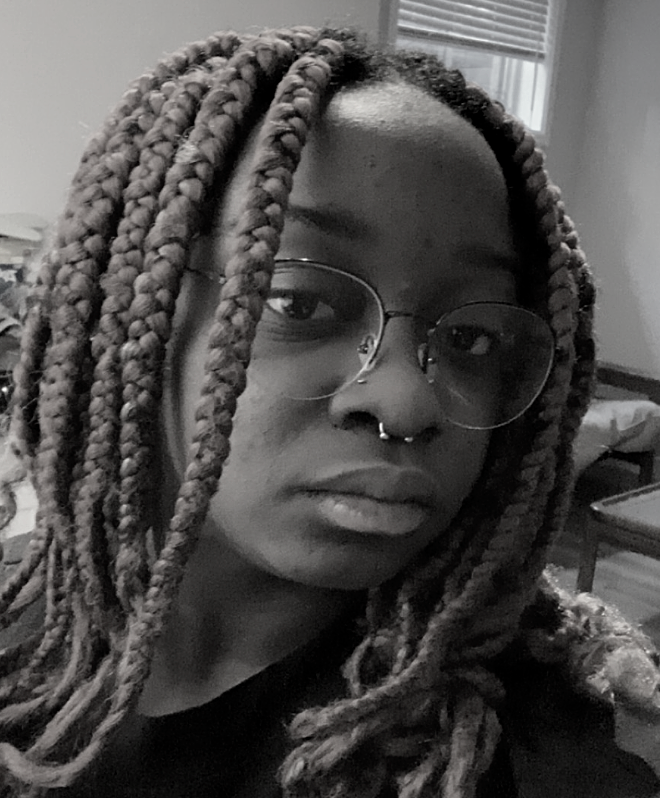

Amaka Umeh, the Dora Award-winning actor perhaps best known for leading Hamlet at the 2022 Stratford Festival, recalls having to “stop and digest” the first half of Sizwe Banzi Is Dead during her first read-through.

“[The play] is so full… it enriches the listener with a crash course in the reality of a Black South African’s experience in that time period,” they said. “But it’s not a very long play. And in that amount of time, [the story] arrives at a breathless pace.”

Umeh, who plays dual roles of Buntu and Styles in the production, said she has a personal relationship with “the necessity to wear different identities” in different roles. What is important to Umeh is understanding how characters fit into roles differently, depending on who they’re with and what is being asked of them in a performance.

“I see it very much in the characters that I play, [Buntu and Styles], one of whom spent a very long time just doing what he was told and wanting to be the ‘Employee of the Month’ every second. And [there is] also this character [who is] an English speaker, [and] is someone who can translate … the messages from the higher-ups to his community,” she said.

Umeh related this to her experiences as a Nigerian, encouraged to learn English at home rather than Igbo, her native language. It wasn’t until they were an adult that they understood the privileges of speaking English.

“I was asking my mom, ‘How come we never spoke Igbo at home?’ There’s a few things here and there [that I know,] like ‘How are you?’, but there was no education in my indigenous language. And the answer was ‘That wouldn’t serve you on a global stage… being an English speaker is what’s going to empower you to survive in this world.’”

Observing the anxieties and realities of navigating the pass system and other apartheid-era systems through Sizwe Banzi Is Dead was a shock to both Otu and Umeh, who both reflected on the parallels between civil rights then and now.

“I was thinking [that] by the time I was born, apartheid was still in effect,” Otu recounted. “And then growing up with ‘Free Mandela’, then Mandela being freed … it’s almost like everything was forgotten,” Otu said, looking back at her Kenyan upbringing.

“I was thinking about which histories we actively remember, [which ones] we choose to remember, and which ones we choose to forget and how important that is.”

Umeh also outlined that many of the audience members in the 1972 premiere of Sizwe Banzi Is Dead were not aware of the circumstances that Black South Africans had to navigate in their own country. “Sometimes it’s almost like we don’t want to listen to each other because we are so capable of bending, morphing, and crafting falsehoods,” they said.

“But there’s something [important] about the ritual of arriving in an artistic space that everyone goes ‘Okay, we’re gathered here to believe’. To suspend disbelief and receive what’s being released into this space.”

Otu believes that the goal of Fugard, Kani, and everyone involved in the creation of Sizwe Banzi Is Dead was to hold up a mirror to society and [understand] how we see ourselves. “It’s a reflection, and only art can do that,” she said.

“Especially in this piece, [it] is a conversation with the audience as much as … with two characters on stage,” said Otu. “There’s a real, intentional kind of relationship between the shared humanity on stage and … what’s happening in the audience.”

Umeh reminds us that although means of escape and spectacle are valuable and enriching, there are issues that we might not know about until they are discussed by others. “I think [art is] very empowering. It can be really emboldening for people who maybe don’t feel like they have access to that voice of truth,” she explained.

Both Otu and Umeh are invigorated by the atmosphere of theatre and performance, especially in regard to Sizwe Banzi Is Dead, which captures an emotional point in humanity through both comedy and societal struggles.

“There’s just something about the act of creation on its own that is very much at the heart of this play. Regardless of the political context we’re living in now, there’s power that you feel when you’re watching the play,” Otu said.

“I think the act of creating … is political. It requires something that is not of this world, to be able to make something and share it with other people, especially as a live experience.”

Sizwe Banzi Is Dead runs at Soulpepper Theatre until June 18. Tickets are available here.

Comments