The Terrible Parents and the Toxicity of the Nuclear Family

Why “family”?

I find all the positive vibes swirling around the concept of “family” highly offensive. When did “family” become a good thing—in fact, the best thing of all?

I remember the good old days when “family” was a bad word.

For those born after 1980, it might be hard to imagine.

You see, back in the 1950s everyone thought families were perfect. Then two things happened: women’s liberation and the sexual revolution. In the 1960s, women’s liberation and the sexual revolution made people think twice about the notion that “family” might be the answer to everything. Women’s liberation opened our eyes to the fact that the institution of marriage is too often responsible for women’s oppression and abuse, and sexual liberation led us to think that sex could be fulfilling outside of a loving relationship and a key to self-exploration and human development. Then there was the psychologist R. D. Laing who theorized that the source of schizophrenia was not a chemical malfunction, but the irrational behaviour of our parents. Then, there were those shocking ‘hippies’ who rejected traditional family life in favour of communal living and polyamory.

People were starting to become skeptical of family life. And then what happened?

AIDS.

AIDS put sexual liberation into lockdown. Sex stopped being about exploration and growth—it was suddenly about fear. People were so afraid of AIDS that they began to believe that monogamy equaled life, and promiscuity equaled death.

Call me crazy, but I think most people aren’t meant to be married and monogamous. People think I’m nuts when I say this. But just look at the ever-rising divorce statistics! Look at prostitution! Look at strip bars! Why do all these institutions seem eternal? Because marriage can’t exist without them; because monogamy just doesn’t suit human passion.

In fact, it is somewhat inhuman to expect us to all be happily married. And too often children get caught in the crosshairs. If a couple isn’t happily married, the woman may get pregnant for the wrong reasons, like to keep the marriage together. It’s no wonder that after the children are born, parents often act like adolescents. The result is that kids feel un-parented and unloved.

Hillary Clinton and the Iroquois got it right. Hillary said, “It takes a village to raise a child.” In the past, many Indigenous North American children were raised in longhouses by extended families; if the kids didn’t like their parents (something that happens too often) then they could chum up with aunts, uncles, or cousins who were a better match.

My play The Terrible Parents is inspired by my own family life. Does it tell the truth about my mother and father? Does it reveal all about my mother’s relationship with the man she fell in love with after her divorce? I’ll never tell. On the one hand, what I have tried to do is reflect the demented emotional reality of my own family drama, while playing wild and crazy with the details. It’s taken me years to understand how toxic my home environment was, and why. My mother—who was sexually abused as a child—was born out of wedlock and raised by various relatives. She married my father at age seventeen to get away from her horrible life. My father—raised in the sexist post-Victorian atmosphere of the 1920s, was searching for a pretty, perfect, doll-wife. Their claustrophobic marital situation practically drove my mother insane. After divorcing my father, she fell in love with a man who would never be able to devote his life to her; he was an alcoholic Roman Catholic, married with six children. My mother had never really experienced adolescence, had never dated, experimented, and never really fallen in love. Is it any wonder that instead of shielding me and my sister from the details of her relationship with her lover, she tried to involve us emotionally, confessing inappropriate sexual details, and asking for advice about their affair?

This is the truth of my own family life; I only mention it knowing full well that your own nuclear family was probably different. But knowing, too, that you probably have your own set of secrets and lies.

Don’t get me wrong; I think love is a beautiful thing. So are children. And some people are perfectly suited to living and loving and sexing one person—and one person only—for their entire lives (i.e. true monogamy).

But most of us aren’t.

The nuclear family is toxic and dangerous. The unnaturalness of it all makes us repress our real ideas and deepest feelings, turning families into little atomic bombs.

And you know—the thing about bombs is—they tend to go off.

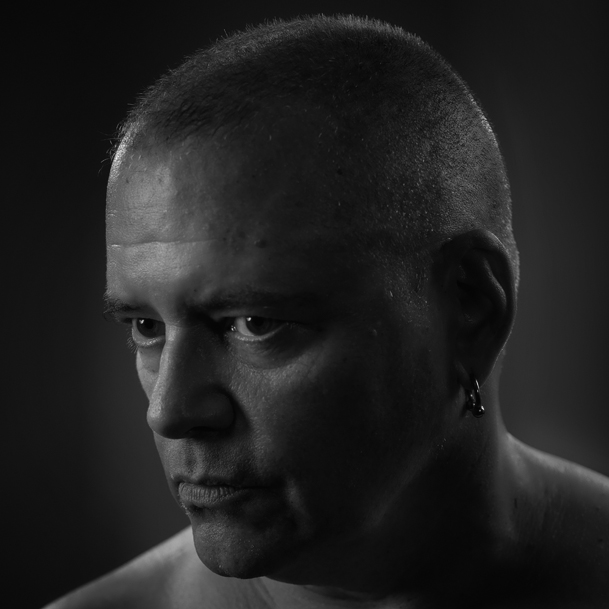

Sky Gilbert wrote and directed The Terrible Parents, which is running at Buddies in Bad Times from April 6 to April 17.

For tickets or more information, click here.

Comments