Decay and Regeneration: Re-Framing the Rhubarb Festival

In many ways, Rhubarb is fundamentally about change. Buddies’ long-running new works festival has had numerous leaders and offered space to countless artists intent on exploring the unknown. That said, under Clayton Lee’s direction, the festival has morphed in ways that would have been hard to predict, even for Lee himself. The 2020 edition (his first at the helm) was perhaps the closest to a “normal” event during his tenure and followed the model for which the festival is known. With the explosion of the pandemic, the 2021 edition saw the event re-conceived as a physical publication, which audiences could safely consume from the comfort of their homes.

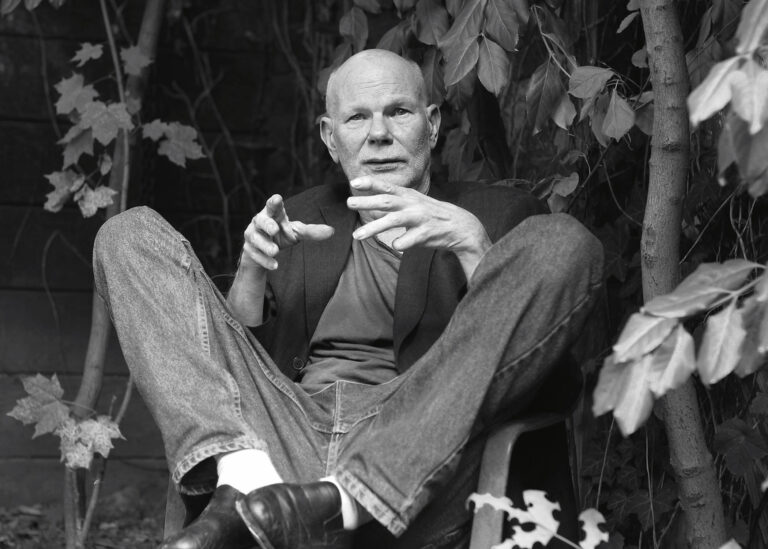

For the 2022 edition, the festival is returning to a limited in-person gathering. Lee invited designer Andrea Shin Ling to conceive a unique installation for the space, and a group of artists have been invited to create performances in response to the site. Chris Dupuis caught up with Lee to chat about international collaboration, taking criticism, and filling the building with mold.

Chris Dupuis: I don’t know if there’s such a thing as a “normal” tenure leading Rhubarb. But you took over the festival at what turned out to be the beginning of a major period of transition for Buddies and a series of unprecedented global events. How has the job of Festival Director been shaped by everything that’s been happening during this time?

Clayton Lee: The festival always allows artists to experiment and I also wanted to explore how we can encourage experimentation in the curatorial process. My first year followed the go-to Rhubarb model of two spaces, with multiple shows in each space. Last year, during the initial pandemic months, it became clear that we wouldn’t be able to have an in-person festival. A lot of companies were going digital and I was often uninterested in the results. So I proposed the idea of the book, both as a strategy to do something different from everyone else and to offer an alternative vision of what the festival could be. After that, it became a question of changing the festival format year to year, as a way to be flexible and responsive to what’s happening in the industry and to ground that approach in the needs of artists at any given point.

This year’s edition of Rhubarb is probably unlike any version that’s existed before. Tell me about what’s happening and why you decided to work this way.

Andrea Shin Ling has designed a large-scale installation for the Chamber and the idea is that all of the work in the festival is a response to what she’s made, physically but also conceptually. This installation consists of thirty-four tree stumps that have been processed in various ways. Some are hand-carved simple forms. Others are these robotically fabricated, computationally designed blobs. We’ve inoculated about half of them with various kinds of bacteria and fungi so there’s the element of witnessing decay and regeneration. In practical terms, it means there’s a lot of mold everywhere. Each day, a new artist or artist team arrives to create their work, and then it’s performed once or twice for the public, which is limited to twenty-five people per performance.

Working this way is obviously practical in terms of limiting the number of people in the space at any given moment. Beyond that, why did you want to use this specific format?

During the application process, we often get proposals for works that are already in development. That means you sometimes have artists helicoptering their work into the space and then helicoptering it out with the aim of taking it on to SummerWorks or Luminato or another theatre company. There’s nothing wrong with moving up the development ladder that way, and it’s a successful strategy for professionalization. But I was interested in shifting away from that and coming up with structures that encourage responsiveness, the book from 2021 being a good example.

In terms of the living installation we’re working with this year, there was an interest in exploring time. In traditional architecture, when you have a problem, you can just throw resources at it. But with bio-design, you have to wait for the organisms to do their thing. Beyond that, thinking about decay and regeneration as complementary processes is profound for me in any number of ways.

Discussions of decay and regeneration obviously tie in with the broader questions around what’s happening at Buddies right now and how Rhubarb fits into that. The festival has been a lot of different things at different points: an incubator for new Canadian plays, a hub for performance art, and an entry point for international queer artists to the city. I know the future of the company is fuzzy. But I’d still be curious to hear your thoughts on the place of Rhubarb in that developing ecology.

I recently reread this interview that Erika Hennebury did with Kelly Nestruck in 2009 where she talked about her vision for the festival and how it fit into the company. And it was kind of spooky to read because many of the considerations she was weighing thirteen years ago are the same questions I’m wrestling with now. It’s difficult for me to speculate about how Rhubarb will function in the future of the company. But what I can say is that I want to actively allow for change to happen and try to understand my role in that process over time. For the moment, I can say that I’m actively and intentionally shifting away from well-made plays and trying to hone Rhubarb as a space for experimental practices. More broadly, I’m interested in contextualizing Rhubarb in the global landscape. There’s a lot of value in having artists from abroad coming in and informing practice, as well as local artists traveling to explore the ways artists are making work around the world. The question I’m always trying to answer with Rhubarb is how we make practice better, which is obviously a loaded term and a loaded phrase. But for me, the tools of that are exposure to different ways of making, both internationally and intergenerationally.

One of the challenges for Toronto theatre artists is that the city isn’t positioned within an international touring network. Shows made here rarely tour abroad and work from other countries is rarely shown. As anyone who’s had the experience of being an immigrant will tell you (myself included), you don’t really understand your own culture until you’ve lived in another culture. I think the same is true of a performance milieu since performance is such a local medium and so performance makers in Toronto often don’t understand their own context.

I think Toronto performance works in three-year cycles. When there’s one influential piece, you can see the ways it bleeds into other works that follow it. How do we interrupt that? We shouldn’t have an ecology that’s only informing itself. I’m interested in exploring how we can let other artists and practices seep into that space, as a way to enrich practice, and internationalization is a big part of that.

When you take over a festival or a theatre, you suddenly have a community of artists and audiences who want specific things from you and feel entitled to point out anything they perceive as a failure. How have you been able to navigate those things during Rhubarb?

The fact there’s been a pandemic has been helpful because I haven’t left my house that much in the past two years. (laughs) But in all seriousness, I invite these kinds of criticisms of the festival because they allow it to shift and grow. My work on the festival is guided by what I think is useful for this context and how that can set up the ecology of the future. There’s also a value in disagreement and the tensions that exist around it, as well as the ways we project our hopes and dreams for an ecology onto someone in a leadership role. My goal is to ground these questions around the future in something generative and nourishing rather than just using them as a way to rip things apart.

During times when Rhubarb specifically (or Buddies more generally) has shifted towards performance art, there have been complaints from theatre artists that their space is being taken away. Do you think there’s any validity to those criticisms?

I don’t think the work I’m programming signals a shift in the company at large because Buddies is a theatre space and has adhered to that for a long time. When I think about flexibility and responsiveness, I think about how Rhubarb is responding to Buddies as a whole, and this programming has its roots in theatre. So how do we introduce other contexts to the theatre space? It’s not a referendum on whether theatre is good or bad. That’s not an interesting question for me. It’s more about tools or strategies for making work that moves beyond the well-made play.

Imagine we’re talking five years in the future, after you’ve finished your tenure as Festival Director. What would you like to be able to say you’ve achieved?

I’m interested in shifting the festival towards being more financially equitable. Rhubarb built its name off the labour of artists, often poorly paid or unpaid. I’ve been able to increase the artist fees, which is why we have a smaller number of projects. In terms of the future, I think Rhubarb will continue to be malleable and flexible based on what’s happening in the community and in the world. The model I inherited was there for a long time. But the circumstances under which I’ve been working have both allowed and required me to reimagine it. And whether the next person recreates that model or envisions something entirely different, that’s part of what a legacy can look like.

Comments