In Conversation: Hannah Moscovitch

Playwright Hannah Moscovitch is currently writing an opera, while her 2016 play Bunny is enjoying an acclaimed run at Tarragon and last year’s Old Stock is opening in New York. Now her 2015 play What a Young Wife Ought to Know, about the ways women navigated love and sex and desire before birth control was made legal, is about to open at Crow’s Theatre. At a time when conversations around female sexuality are increasingly necessary, she talked to us about the play’s real-life inspiration, awful old-school birth control methods, and why looking at women’s history is especially important right now.

On the real-life stories that made Moscovitch want to examine women’s sexuality before birth control was legal or accessible

I picked up a book at a garage sale. I think it was 75 cents. It’s a book of letters written to Dr. Marie Stopes—she was a pioneering birth control advocate in the 1920s in England. Women were writing to her, asking her for help with birth control. Many letters don’t really distinguish between birth control and abortion, because they were both illegal.

It was this weird entry into this world that I had never heard of, and it was women, all women. Women were the subject, even when husbands wrote in. And there was a helplessness in the love husbands had, because they wanted their wives to live. They wanted them to survive childbirth.

[The letters came from women] worldwide. You get to see letters from Canada, and letters from Australia, and letters from India. They’re predominantly working-class women. Because birth control was illegal there was a black market, and it was extraordinarily expensive. That was part of the problem. The working class— often they’ll say things at the beginning of the letters like: I saved up the money to buy the paper for this letter. I didn’t buy butter this week so I could buy paper so I could write to you.

Reading the letters, I felt like: This is a world with machine guns and telephones and electricity. It’s a modern, technological world. And it just shows the difference in women’s lives before and after the legalization and proliferation of birth control.

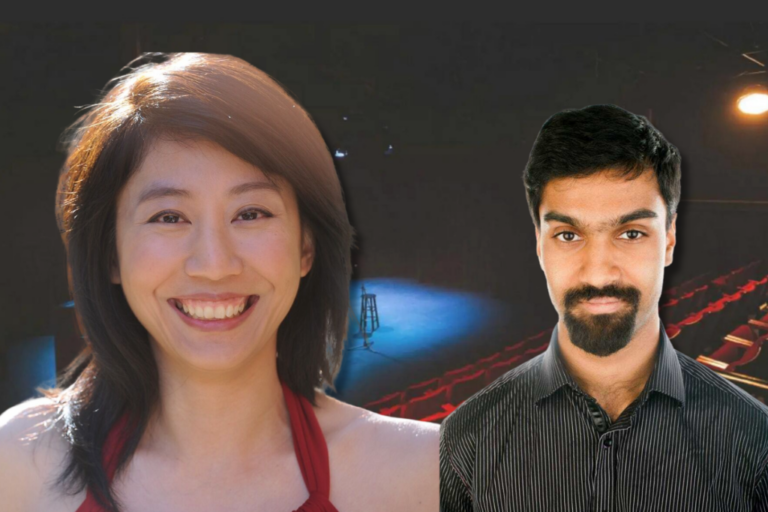

Liisa Repo-Martell and Rebecca Parent in What a Young Wife Ought to Know

How the letters uncovered truer narratives about abortion

What is striking about the letters is that they were so in contradiction to abortion narratives about some young unmarried girl who gets knocked up by a rich man and then has a back-alley abortion and dies. That story is omnipresent. But these are married women who want abortions, with husbands who love them. Almost every letter starts with how much they make and how many children they have. So it will be like: My husband makes eight dollars a week, and I bring in two dollars doing laundry. I’ve buried three children, had four stillbirths, two miscarriages, and I have four living. Can you please help me to stop having more children? My womb has prolapsed twice now, and every time I go into the hospital it’s so much money, and the children need me at home. Every letter sounds similar, kind of like a scream into the dark, written to a woman they’d never met.

Why it was refreshing to read women speaking candidly about sex

It’s so strange, when you think about the literature of the period and how masked all of that stuff is. Then to read this thing where it’s just fully on the table, you know? They’re like: here are all the things that went wrong in my childbirth. And birth is something that’s so often alighted. Even in movies today—birth in movies today is exactly like fucking used to be before HBO. It’s a woman in a sheet, a little bit of sweat, she looks fulfilled but tired. No! Twenty-nine hours of labour does not look like that! But we see that over and over again. In a way this is the opposite of that: everything unmasked, the dirty, slutty, gothic side of what birthing would have been like.

On the problem of sexual pleasure

Desire is actually a problem in What a Young Wife Ought to Know, and in the letters. Some of these women are pleading to be able to continue to have sex with their husbands without having babies as a consequence. What if you’re twenty-three, and you’ve been married since you were eighteen, and you’ve already got four children? You want to fuck your husband once or twice more before you die.

To women whose uteruses had become prolapsed from so many pregnancies, often doctors would say, you have to stop having children. [Women] would ask, how? And [doctors] would say, that’s not a medical question, that’s between you and God. So they’re stuck in a marriage with desire but no way to fulfill it. What do you do with desire in a marriage where you cannot fuck your husband without the consequences being disfigurement and death?

Liisa Repo-Martell and David Patrick Flemming in What a Young Wife Ought to Know

The horror of early birth control methods

Some of them shocked the shit out of me, like using acid. It’s apparently spermicidal. That’s a scene in the play. They would bake acid into something like butter—it looked like a brownie—and you would stick it up your vag. And it would burn you and your husband, but you could have sex. I know, it’s grim.

The middle class sometimes went for abstinence as a solution. There are cases of men writing in and being like: My wife doesn’t want to have any more children and so she spends a lot of time in the garden. Stuff like that. Or they went for very, very expensive illegal, and often botched, abortions.

What hasn’t changed since the 1920s

There is a kind of isolation to bearing the burden of labour and childbearing alone. That alone-ness was just so stark in the letters, and that felt contemporary. Maybe it’s strictly true to heterosexual relationships, but if you’re a woman and [pregnancy is happening within] your body, to some degree, it’s going to be your responsibility more. That’s inescapable. However much you love your husband, there’s going to be some places where he cannot follow you. And that will make you feel isolated. That’s something that I learned about when I had my own child.

On how conversations about the play have changed since its premiere three years ago

When we were working on it in 2015, people kept saying, “Why do you think this is relevant?” Artistic directors said that, too. I kept having to defend it. I felt like what was being said on some level was that women’s history wasn’t relevant. What the fuck?

[Women’s lives before birth control] was this extraordinary thing, an unusual part of women’s history, that felt lost to me. And, like with anything else, it can come back. The leader of our Conservative party right now is against abortion, openly. Mike Pence is second in line for the presidency in America, and he is stridently, in all cases, anti-abortion. It’s annoying to be too alarmist, but it’s worth saying.

It’s amazing to me that three years ago, interviews started with, “What’s relevant about this?” And now they’re starting with, “This is so relevant.”

Comments