In Conversation: Patricia Rozema

After seeing Mouthpiece—the Quote Unquote Collective play by Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava that took the Canadian theatre scene by storm in 2015—esteemed Ontario-born filmmaker Patricia Rozema took it upon herself to adapt it for the big screen. Below, Rozema talks about adapting Mouthpiece, theatre and film, and her career as a filmmaker.

Starring Nostbakken and Sadava as two halves of a single woman, Cassandra, Mouthpiece documents the recent death of her overburdened mother and the subsequent funeral preparations. Written by Nostbakken, Rozema, and Sadava, Mouthpiece premiered in 2018 at the Toronto International Film Fest, and is part of this year’s Forest City Film Festival in London Ontario alongside Rozema’s 1987 indie hit I’ve Heard the Mermaid Singing starring Sheila McCarthy.

Beginning in 2016, Forest City Film Festival is an annual juried competition for features, shorts, documentaries, and short animations by artists connected to Southwestern Ontario. FCFF also presents a selection of the best Canadian films of the current and past years, industry workshops and networking, a screenplay competition, and filmmaker Q&As.

On Why Mouthpiece Spoke to Her

It really was a great play. The audience vibrated before it started because the word was already out about it. It was one of those exciting cultural moments. Amy and Norah—keep an eye on them. They addressed various issues about being a woman today, in Toronto, as themselves. Their attitudes toward their bodies; their attitudes toward their inherited self-critique; their attitude toward their inherited sexism, or internalized misogyny, or self-doubt. It was very operatic in the sense of the highly theatrical and the physical—a lot of dance much of the time, and a lot of musical numbers. So I came to that. And everyone comes to me and says, “How did you think that could be a film?!”

I just was so excited by it and that’s what I responded to. I think that the combination of intensity and humour, they way they could really make fun of themselves, and clearly [their] work ethic because it was at a level of precision that was thrilling. I met with them and kinda on a whim said, “I’d like to throw my hat into the ring to make this into a film.” They were totally stunned.

On Adapting Stage to Screen, from Beckett’s Happy Days to Mouthpiece

The Beckett Estate doesn’t allow the tiniest bit of intervention with the materials—no interaction, no development. So I took that very seriously, you know that’s the art of contention. I put it on a volcano because it’s usually performed in a pile of sand in the theatre, but [a pile of sand is] not what he meant. He just meant somewhere where there’s no life. Somewhere that the sun beats down relentlessly and there is no growth.

[Mouthpiece] was a transformation, a re-envisioning. So we went up to this little cottage and just free-associated. First I said [to Amy and Norah,] “Write a TV show,” and then they didn’t really know what to do and nothing really came of it, and [they] didn’t know [the rules]. And I thought that that’s good that you don’t know the rules. You can be more original you know? But none of us could get fired up about a TV series about [Mouthpiece]. So then we decided to do a feature and suddenly everyone’s shoulders went down and we were, “Okay, well this is how it would begin.” And we’ve got one hour so far, so what could we keep? We had to add the mother because the mother had died in the story. Let’s see the mother; let’s know more about her.

Maev Beaty and Taylor Belle Puterman in Mouthpiece (Patricia Rozema, 2018)

On Mother/Daughter Relationships and Grief

I’m a mother. I’ve had kids. My mother died about the age [that Cassandra is in Mouthpiece] so I felt like I really had legitimate input. I had a legitimate voice in this creation. They [Amy and Norah] didn’t know what that would feel like. They had more anger towards their mothers, although they both have great relationships with their [living] mothers.

The mother [Elaine, played by Maev Beaty] just took it and took it and took it and just can’t take it anymore. And I wanted to delve into that a little more, the differences between generations. Who’s to say what’s right? Was it so bad that she stayed and loved those kids every day, every hour, even if it was at the expense of her self-expression?

On Recurring Themes in Rozema’s Work

There will always be the tension [in my work] of, how will I spend my time on earth? My first film was called Passion: A Letter in 16mm, and it was a letter by a woman played by Linda Griffiths (who was quite a hero in the theatre scene in Toronto and died way too young from cancer). She was struggling with a passion for excellence in her work and passion for another, and I created this sort of unusual format. I was jealous of poems and songs where you could just sing to yourself. You know, sing in first person and not have to identify or show everybody everything. So I made [the film] first person—she speaks directly to the camera and explains a break-up. She goes through this letter in 16mm. That was my first exploration of that tension that still comes out in [my work]—love of a human, or love of making something that lasts and stays. Those are tough. Theatre doesn’t last and stay, and that’s why I can’t do it. It’s so much about capturing what slips through your fingers so quickly. Theatre is too transient, too ephemeral [for me].

On Making the Ordinary Extraordinary

I’m more interested in taking an ordinary person, rather than a heroic, extraordinarily beautiful person. I guess it seems kinder in my mind. I was moved by other movies like that. I’ve said this before and I’m suspicious of it, and maybe it’s not good, but I have this feeling like it’s something I can offer. It seems to me that people all over the world, myself included but less so now, [have] these grand emotions and an appreciation of beauty; but a real doubt that it’s for you, or that you can reach it or ever make it. If I can show that person who isn’t the big spectacle that gets noticed and has the cameras trained on them; if that person can get respectful treatment and have their heartbreaks and their aspirations treated lovingly with dignity and with heightened import; that’s worth spending life on. Why I’m slightly nervous of it is because it [might feel] like, “Here, I’m giving the little people something to feel about.” That’s my fear, that it’s from a stance of superiority. But it isn’t, I know that I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing is about my own fear, that I was drawn to the mermaids singing but they weren’t singing for me.

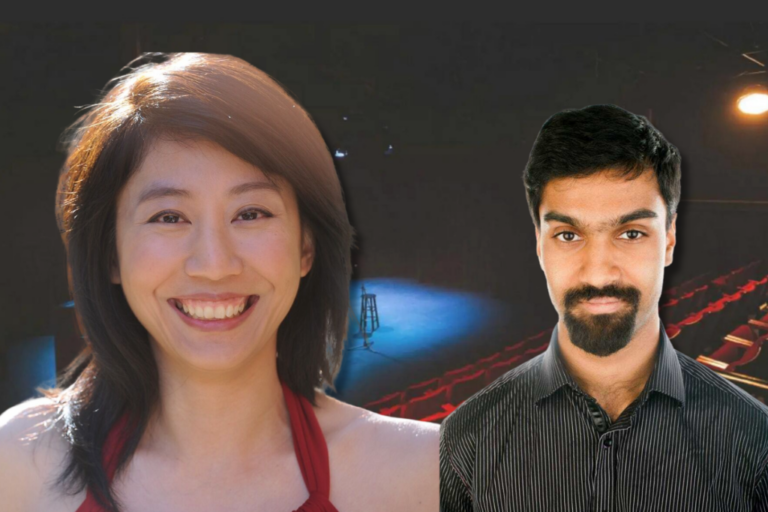

Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava in Mouthpiece (Patricia Rozema, 2018)

On Navigating the Male-Dominated Film Industry

I don’t know if it was being the only woman in a predominantly male [Toronto] film scene or predominantly male film scene in the world, [but] I think I probably leaned more into charm than I otherwise might have. I felt like the only way I’m going to get away with this woman-ness, and my concerns and my issues, and the things I’m drawn to is if I make it kind of funny. But I believe in humour anyway. If you can make people laugh you can go anywhere together. They’ll go with you, and I’ll go with them!

On Telling Women’s Stories

I think that we were all tuned to the issues well before #MeToo. I was shocked at how widespread it was suddenly and I was shocked that abusive men lost their jobs. I did not believe that a collective outpouring of stories and upset would get guys fired. I didn’t believe that this is something we learn over and over again in society: actually you can change things. A collective, if enough voices say the same thing, can actually change things that we [previously] believed were just life. I think it was Gloria Steinem that said, “We didn’t think of it as sexual assault, we thought of it as life.” There are so many things like that.

When [Amy and Norah] were making the play, they hesitated to use the word feminist because they thought no one would want to see it if it was called feminist. I have been freer with that term since the beginning. I think it’s coming from the very repressive background I came from, and then breaking out of that, and then being gay, and deciding to live the way I want and not hiding it. You are already so outside the mainstream that who cares if you add feminist onto that? It’s the least of the reasons people are going to reject you.

Women are having a moment! The [Forest City] Film Festival is full of female film directors, and the mother-daughter story is finally getting examined! Mothers were either dead or non-existent for most of the history of cinema. So this is a huge moment. That’s why women need to be behind the camera, or be the playwrights, or be the theatre producers because they have the understanding and investment in these stories that haven’t been told yet.

Comments