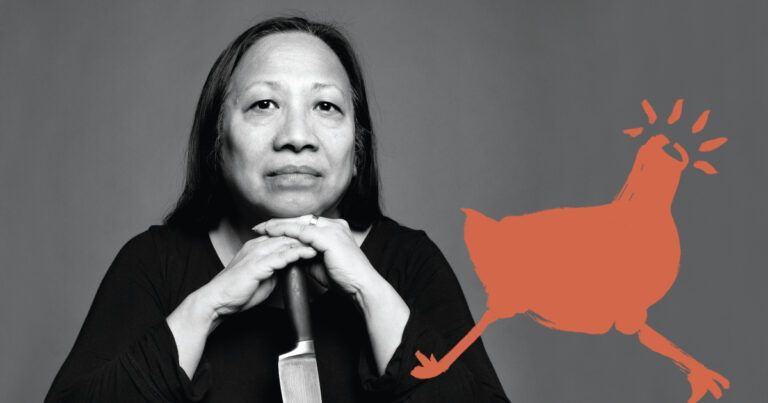

In Conversation with Alison Wong on ‘nowhen’

I am walking through High Park with a small group in the sweltering summer heat, and we all have our headphones in as we listen to a Bengali man share the story of his ancestors and his migration journey to this land many now know as Canada. There is an actor who leads us through High Park – from the Parkside Drive and High Park Boulevard entrance, up the steps to the Greenhouses, and then in between some trees by a picnic shelter.

The actor, in beige, loose-fitted, ancient, robe-like clothes, guides us through a route that I have never been through before while performing the story that I hear in my headphones. My ears are filled not just with the narration that recounts an intergenerational tale of war, displacement, survival, resistance, and triumph, but also of rich soundscapes from the natural world. As we move along this journey, my eyes take in the beauty of High Park and the strange dissonance of following a performer through a public park as families pass by, as children play in the background, and as a train trolley waits along a trackless road.

I’m led into the High Park Amphitheatre, where I sit socially-distanced from the other theatre-goers around me, who are slowly filling up the space after journeying through their own unique paths led by other actors. These actors, in the same or similar beige clothes, walk up and down the amphitheatre steps, greeting each other in various languages. I hear Spanish, Jamaican Patois, Bengali, Yiddish, Anishinaabemowin, and other languages I can’t quite name.

And for the next half hour, I’m transported into a whimsical experience of language, colour, sounds, and the repeated question of, “where are you at?” as the performers weave in and out of the audience with dance-like movements. I feel the earth underneath my bum, the grass tickling my thighs, and the sun beating down my shoulders in what feels like a meditation and homage to the natural world we all find ourselves in.

I feel the earth underneath my bum, the grass tickling my thighs, and the sun beating down my shoulders in what feels like a meditation and homage to the natural world we all find ourselves in.

That’s just a snapshot of the nowhen experience that is part of Canadian Stage’s Dream in High Park programming.

nowhen is a Canadian Stage production in collaboration with the Department of Theatre, School of the Arts, Media, Performance & Design at York University, presented in partnership with Summerworks. It’s a collective creation led by York University Theatre and Canadian Stage MFA Candidate Alison Wong with Cole Avis, César el Hayeck, Djennie Laguerre, and Miquelon Rodriguez, and adapted from stories originally published in Living Hyphen, an arts community I founded, that explores what it means to live in between cultures as hyphenated Canadians.

When Alison Wong first reached out to me randomly via Instagram direct message last summer, asking where she could purchase a copy of Living Hyphen’s inaugural issue called Entrances & Exits, I had no idea of the magic that would later unfold. I had no idea that just a month or so later, we would be meeting for a socially-distanced coffee and then a walk through High Park to seriously discuss the possibility of collaborating to adapt stories from the magazine into a staged production. I had no idea that this seemingly trivial interaction would lead to the creation of nowhen, a stage production of seven paths and seven stories, all converging in celebration of the thing that unites us all – place.

Now here I am today – nearing the end of nowhen’s run at High Park from August 8th to 15th – experiencing her vision come to life.

I had the privilege of interviewing Alison to chat about her process in creating this immersive, diverse, and experimental production, how the pandemic has influenced her approach and her perspective, and the importance of the concept of place that is at the centre of nowhen.

On her relationship to High Park

nowhen came about in the first summer of the pandemic, as I was spending a lot of time in the park trying to figure out what kind of storytelling I wanted to make happen as a part of my thesis production. Because we were in isolation, I felt like I was getting to know the park in a deeper way. Before the pandemic, my experience of walking through the park was, “Oh, this is a park. This is a space I walk through.” I didn’t think much about its past history, its living history. I didn’t think much about what happens in my day-to-day life that actually impacts my access to this space and my ability to move through it.

When the pandemic happened, High Park was one of the few places that was available to me, and it became a kind of a sanctuary. It took me in and it gave me a lot. I wanted to make a piece that could express that, and that showed what was shifting internally as I was moving through that space and the awareness I was starting to have. I wanted to explore how I could tell that story.

On curating Living Hyphen’s stories along the different paths

I was reading a lot of poetry and a lot of mythology during that time. I was thinking of origin stories and creation stories. Interestingly, that led me to Living Hyphen. When I got the first issue, I read it cover-to-cover in one sitting, and a lot of those stories stayed with me.

The next time I was at the park, I was thinking about them and I realized that there was an experience of locating ourselves and our stories in place, especially during a time when we were really stuck in the same place.

Sometimes I would read a story, and I would think, “This story happens on this path.” I would just know. I just had a gut feeling about it.

Then, of course, when I started working together with the creative team, that would sometimes change. They would tell me, “No, Alison. This story really belongs on this path,” and seeing their vision for it made me realize how that made more sense.

Overall, I’ve been thinking a lot about my position and the responsibilities I have in relation to this place. A lot of the stories in Living Hyphen touch upon those ideas as well, and I really wanted to make something that allowed for that storytelling to happen in tandem with place.

On developing a production set in nature

Each individual actor has really developed a relationship to the path that they have been assigned to. Their path has become their scene partner. Because the physical environment changes day-to-day, the actors have had to learn their paths and know it really well. They also need to know when something is different. They need to be able to respond to something that is happening in the moment and have that be a part of the story that they are telling. Much in the same way that you rely on a scene partner to be consistent, you also leave room for these great moments when something is improvised, when the rhythm locks in a different way that is just magical. We’re finding these parallel experiences between the actors and their paths in the park.

On the challenges of the pandemic

We had to work remotely and it was really strange for the team to make a piece about our connection to place, but not be together in the same place. And not just that, but we also couldn’t go to the place that the piece is about.

There had to be a lot of trust between us. In a way, that intentionality and desire and energy and focus to work with the park even though we couldn’t be there together fueled the process. It opened up some imagination amongst the group to challenge ourselves with this uncharted process. If we had been a world where things were business-as-usual, I wonder if there would have been more hesitancy to try something new. At that point, everything was out the window. We weren’t making theatre in the way we had been making theatre. So we were all just game for anything. It was a gift in a way.

We weren’t making theatre in the way we had been making theatre. So we were all just game for anything. It was a gift in a way.

On bridging the natural world with technology through the Echoes app

I was really curious about this experience of people being together in place but being aware of their state as an individual. We all experience time in our own way and the pandemic really amplified that. This was potentially going to be a performance experience that people were coming back to for the first time after a year and a half of isolation. How do we land into that? I didn’t want to create a piece that would just thrust us into the Before Times. I didn’t want to not acknowledge the pandemic.

We’ve all been going through such a difficult experience and it will take time to process and work through it together. This idea of letting go of time – or not letting time or our concepts of time restrict us – but also allowing ourselves to celebrate being together, to connect to space together, to share space together – was a really big part of the vision of the experience that I wanted the audience to have. The Echoes app surprisingly lent itself to those values.

Aidan Ware, who is the technical director on the project, found the Echoes app. When I started playing around with it and building these tracts, I really loved that what you hear is really dependent on where you are standing, where are you moving to. That means that when I am moving with a group of ten people and someone is ten feet away from me, they are going to hear something five seconds before I do. But the way we’ve built the performance – at least, what we’ve attempted to do – is still have that moment be shared by everyone in the group. The actor has an important role in holding that moment so that even though the audience members are experiencing this in staggered moments in time, the moment is still complete and still shared.

That’s the metaphor for the whole piece. We can intentionally be in space together and relate to each other even though our timelines are different.

On the diversity of language highlighted in the play

I am very lucky as an artist to have worked in multiple countries and in different language settings. And as a settler here in Canada, I’m very aware of how Indigenous language loss has impacted my understanding of colonial history in Canada. I bear a responsibility to learn the language in the same way that when I am a guest in another country, I try to learn how to speak even just basic phrases. It’s out of respect.

That was a part of the relationship that we were all navigating between these stories of hyphenated experiences so generously shared by the writers from Living Hyphen. Language was a part of these stories. But I also knew that if we were highlighting the languages that have been brought to this place, then we must also spend time honouring the languages of this place. For the land that High Park sits on, that’s Anishinaabemowin. And so a part of the artistic process that we all went on together as a team was learning some Anishinaabemowin. That was important to me.

When I was curating these stories, I knew I wanted the actors to bring their own language experience outside of English into the performance. That’s something that I’m really interested in as a director. We have such talented actors in Toronto and what we call Canada who can act in English, but who also have such diverse language abilities. We don’t platform that enough unless it’s a very culturally specific performance or piece of theatre. I didn’t want to centre English as a target language and it just made sense in our process to have language learning a part of building our intentional relationship to place.

Reckoning with Canada’s genocidal past and continued colonization of Indigenous nations

The work definitely sits in this moment. There wasn’t any way that we could look at creating a piece together that speaks to our relationship to place without confronting this. Every person who was a part of the team is on their own journey with that. We dedicated time to locate ourselves and our story not as characters, but as ourselves, as artists working through this process. We dedicated time to locating where we are on this journey.

That’s a big question that comes up in this piece a lot: “where are you at?”. We visited and revisited this question in our rehearsals, in how we began our days, how we greeted our paths. That was something that was critical for us to make space for.

On what the audience should take away from nowhen

I hope the audience sits with this question themselves. Where are you at?

I hope they really actively consider locating themselves, what their relationship to this place is, and what their responsibility to this place is. I hope that they are embodying that process and not just intellectualizing it.

nowhen runs in High Park through August 15.

Comments