REVIEW: Studio 180 Theatre’s Four Minutes Twelve Seconds stirs one moment and puzzles the next

Constructed as a series of reveals detailing events set before the play’s start, it may be best to experience Studio 180 Theatre’s Four Minutes Twelve Seconds, directed by Mark McGrinder at the Tarragon Theatre Extraspace, with no knowledge of what’s to come. There are so many twists, it occasionally appears playwright James Fritz is satirizing the plotiness of thrillers — though at other points he embraces these narrative swerves with earnestness, or something resembling it.

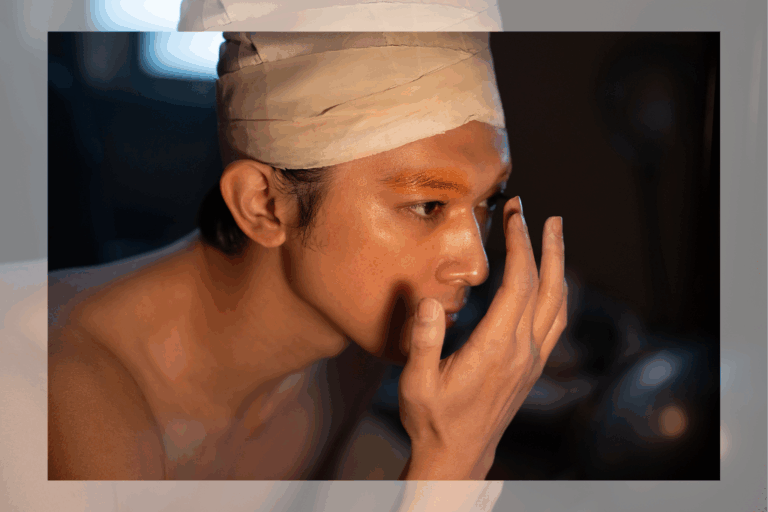

The play in any case centres on Di (Megan Follows) and David (Sergio Di Zio), a married couple living in Scarborough (for the North American premiere of this British play from 2014, McGrinder has modified location names). After their 17-year-old son Jack, who never appears on stage, returns home wearing a shirt covered in blood, Di and David panic, stained garment in hand: who’s done this? Turns out it’s the brother of Cara (Jadyn Nasato), Jack’s ex-girlfriend. Cara dumped him after a video of the two having sex surfaced online. Owing in part to the sweet Nick (Tavaree Daniel-Simms), a schoolmate of the young couple, information surfaces indicating the sex was likely non-consensual, further distressing Di and David.

Fritz has named fellow Brit Caryl Churchill as an influence, a fact visible in the play’s snappy, cutoff-ridden dialogue, made up largely of conversations slow to unveil their subject. And though Fritz’s deployment of this style can veer toward affectation — he sometimes obscures trivial information until it’s more aggravating than engrossing — it does serve to produce an aura of mystery, along with a degree of forward momentum.

Di emerges as our detective. She’s the only character with any real will to uncover the truth of what’s occurred and thereby push the drama forward. She collects evidence, meets with both Cara and Nick, and concocts idiosyncratic plans to resolve the conflict, all the while fighting to stay grounded. As the script ties itself in narrative knots, Follows never loses sight of the situation’s overwhelming nature; it’s as if Di’s fending off a panic attack at every moment, grabbing onto any scrap of hope she can, clutching to it for survival.

Critics at Toronto’s daily newspapers have had very strong feelings about this (in my view) rather middle-of-the-road production; for the Globe and Mail’s J. Kelly Nestruck, the script is dated and the direction “embarrassingly awkward,” while for Toronto Star’s Joshua Chong, the show is “pretty close to perfect.”

I see where both writers are coming from: the show is conflicting, with much to both stir and puzzle. On a certain level, Fritz’s twists rouse, and are entertaining in the comforting manner of genre fiction purchased at an airport. But they never stop coming off as constructed; the play prioritizes shocks above all else, at times seeming more interested in manipulating the audience than staying true to its characters.

As for McGrinder’s direction, I find the production effective on the level of rhythm, pace, and, often, performance (Di Zio is one of Toronto’s most metamorphic actors, transforming from role to role enough that it usually takes me a few minutes to recognize him). But McGrinder realizes the physical world of the play is in a less complete manner. Jackie Chau’s set of angular modern furniture is sleek, backing up the text’s hints that Jack’s family is wealthy in comparison with Cara’s — yet the actors don’t get many chances to interact with it, making it feel oddly tertiary. And while lighting designer Logan Raju Cracknell provides extra theatricality via occasional isolations of Follows’ Di, the choice to illuminate an unimportant upstage bowl of apples during nearly every transition grows confusing.

McGrinder has opted against selecting a specific angle for his production, writing in his director’s note that distilling a Studio 180 show down to a single idea “has never been more challenging than it is with Four Minutes Twelve Seconds.” Instead, he writes, the play is a catalyst for conversations around “consent, privacy, masculinity, sexual assault, and the perils of technology.” Embracing this thematic soup rather than picking a defined direction doesn’t exactly help with bringing the text into the present day.

That said, I’m glad to see the show has two student matinees scheduled each week. The relevant subject matter, winding plot, pulpy 80-minute runtime, and pair of heartfelt performances from Nasato and Daniel-Simms — young, emerging actors — mean high schoolers in particular should find plenty to get excited about.

Four Minutes Twelve Seconds runs until May 12 at Tarragon Theatre. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Comments