REVIEW: National Ballet’s Procession tangles the lines of sorrow and sensuality

Procession, the National Ballet of Canada’s brooding and stylized world premiere ballet, rushes to the stage with startling vitality — and does so at a funeral. For its season opener the National Ballet tapped Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber, two of the hottest names in contemporary dance, to create a custom work, and the result is a solid and searching meditation on the force of funerary rite and the porous line between performance and reality.

Smith and Schraiber owe much of their style to Gaga, a technique created by Ohad Naharin, the former artistic director of Batsheva Dance Company, where married couple Smith and Schreiber met. Procession involves some of Gaga’s hallmarks — a mix of sharp and rippling movements that prize inward sensation over outward polish — as well as flickers of neo-expressionist choreographer Pina Bausch and the balletic arabesques and deep plies the National Ballet company is comfy among.

Before the house lights drop or the curtains rise, a single dancer dressed in a tuxedo coolly leans against the proscenium wall, as though he’s just snuck out from a stuffy gala to watch idly as the orchestra tunes. The casual gesture carries theatrical weight. It’s the first of many signals that Procession is not just a spectacle but also a lifelike experience. Like him, we too have arrived on opening night in formalwear (or close to it) ready for the ritual of live performance.

When he dips away, the curtain lifts to reveal a minimalistic stage lit in heavenly bright light by lighting designer Bonnie Beecher, which bounces off of silky white drapes at backdrop. As dancers in elegant black evening wear walk on stage, so do cellist Coleman Itzkoff and soprano Rachel Wilson, who sings a chilling rendition of Funeral Music for Queen Mary by Henry Purcell in a knees-bent, hands-on-her-thighs pose as the orchestra plays softly beneath her.

While the production is billed as contemporary, there are purposeful classical echoes. For starters, the Baroque score, dominated by Purcell (which later turns to brighter Ravel, Mahler, and Vivaldi), evokes ballet’s European origins. The opening tableaux are rather courtly, reminiscent of ballet’s foundations as an aristocratic ritual. And the large ensemble — 13 women and 19 men — dance in tight and disciplined formations, uniformity and symmetry being a key value in classical ballet.

Despite Procession’s conceptual richness in breaking the fourth wall and referencing ballet’s storytelling architecture, the elegiac first act is sleepy, with more than a few patience-testing scenes. At one point, the dancers exit the stage achingly slowly and in total silence. In another, two opposing lines of men and women hold blank expressions while making incremental foot gestures. We are perhaps being implicated in the tedious endurance of ceremony, but the pacing slides from meditative to deadening.

But there are moments in the first act where Procession beams. There’s no storyline, yet plenty of narrative heat and suggestion. Isabella Kinch, Spencer Hack, and guest artist Alexander Bozinoff are forceful in a pas de trois that reads like a love triangle. They push, pull, and toss each other — and one even stands on another’s chest. It’s unclear what they want from each other (or if they even know) and that tension plays out beautifully.

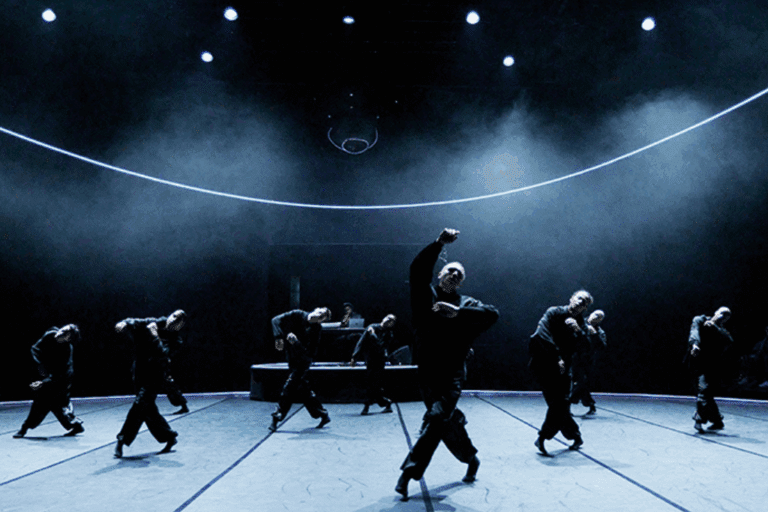

Later, the male dancers perform an explosive first-act coda atop carefully arranged chairs that to me feels like a somber yet energetic Hora. The scene tips into uncanny comedy when dancers stand up and yell or leap into stiff postures like fish out of water. The audience laughs, but rather than resulting from outright humour, it may be the only reaction available to the jumble of alien motions.

After intermission, the dancers return with hair loose and jackets shed. The dances become fast and feral, the mourners now manic. Three men wrestle playfully, and a hearse rolls into the background, which if anything brings lightness — not grief. The mixed imagery adds to work’s wide refusal to close grief and desire into neat boxes.

Kinch, Connor Hamilton, and Genevieve Penn-Nabity’s solos and duets are restless and sharply etched. Meanwhile Hannah Galway and Christopher Gerty’s fluid and sensual pas de deux comes charged with sinuous tension. They wrap and climb one another’s bodies as though they can only see each other through touch, and Galway straddles Gerty’s shoulder in profile to the audience with a purposefully sickled foot (usually a cardinal sin in ballet) draped over his hip.

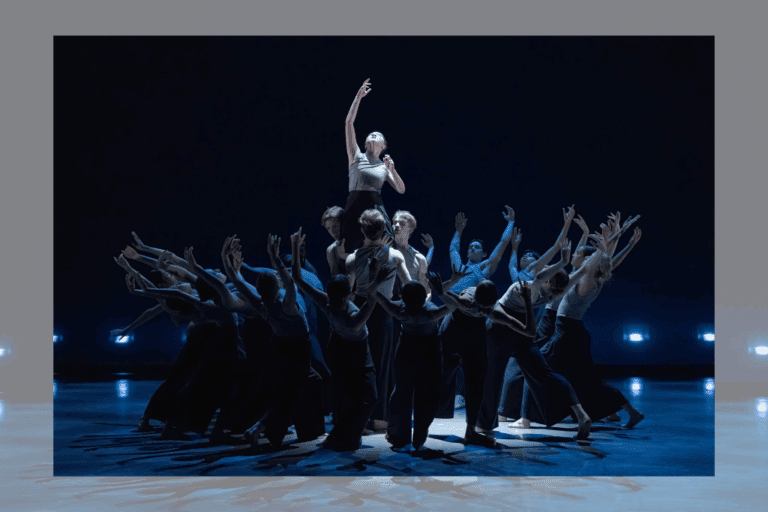

It culminates in a high-voltage frenzy where the full cast flings themselves with abandon, but the energy halts as Itzkoff and Wilson wander toward the front of the stage as the curtain begins to lower. Wilson gives another haunting performance, this time to Musick for a While from Oedipus by Purcell.

Just as the show began, with a lone figure at the threshold between the performance and life, so too does it end. Ben Rusidin appears in front of the curtain, holding it open just a crack, a membrane between worlds. With a held, imploring look to us, he ushers the musicians back into the searing light on stage. What does he want us to know? There is no single answer, but one thing feels certain: the looming force of a communal death march serves as a relentless instigator for tangled emotion.

I left Procession moved, but I struggled with Smith and Schraiber’s heavy reliance on Gaga and their outspoken indebtedness to Batsheva, which Israel considers one its best known global ambassadors. Procession receives funding from the Azrieli Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Israel’s largest real estate company, which has seen ample recent protests at other performances around Toronto. I didn’t personally witness protests at Procession, but I was left wondering about the ethics of Smith and Schraiber acting as indirect cultural ambassadors, and how much such political implications should or shouldn’t be taken into consideration when watching the show.

The artists were excellent, but their virtuosity worked, in a way, to complicate the political context. Watching them inhabit Gaga’s sensorial language on Canada’s national stage with devotion made me wonder: whose freedom of movement does this form ultimately serve?

Procession runs at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts until November 8. More information is available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.

Thank you for speaking on the ethics and adjacent discomfort of this production!

Thank you, Lindsey, for pointing out that this production is implicited in Israel’s genocide. The truth should be told.

Exciting review! Makes me want to go see it if it’s not too late to get a ticket!