REVIEW: Broken Shapes at the Theatre Centre/Broken Shapes Collective

After four long years, Rimah Jabr and Dareen Abbas’ Broken Shapes has made it to the stage in a stunning display of visual and performance collaboration.

Developed in residency at the Theatre Centre and originally slated to premiere in 2020, Broken Shapes is a hybrid performance that examines grief and healing through movement, projections, and visual installations. At 70 minutes, it’s a compact and artistry-laden exploration of themes that, despite plenty of abstract movement and video projections, translate beautifully to the stage.

Broken Shapes tells the story of a young woman trying desperately to piece together the remaining fragments of her late father’s architectural work. As she peruses his unfinished designs, she reflects on moments from her childhood and the stories he used to tell her, revealing a darker past filled with doubt, suspicion, and war. From short movement sequences and a moveable set to hidden props and segments of voiceover narration, Broken Shapes explores the ways in which we grieve and how our memories affect our reality.

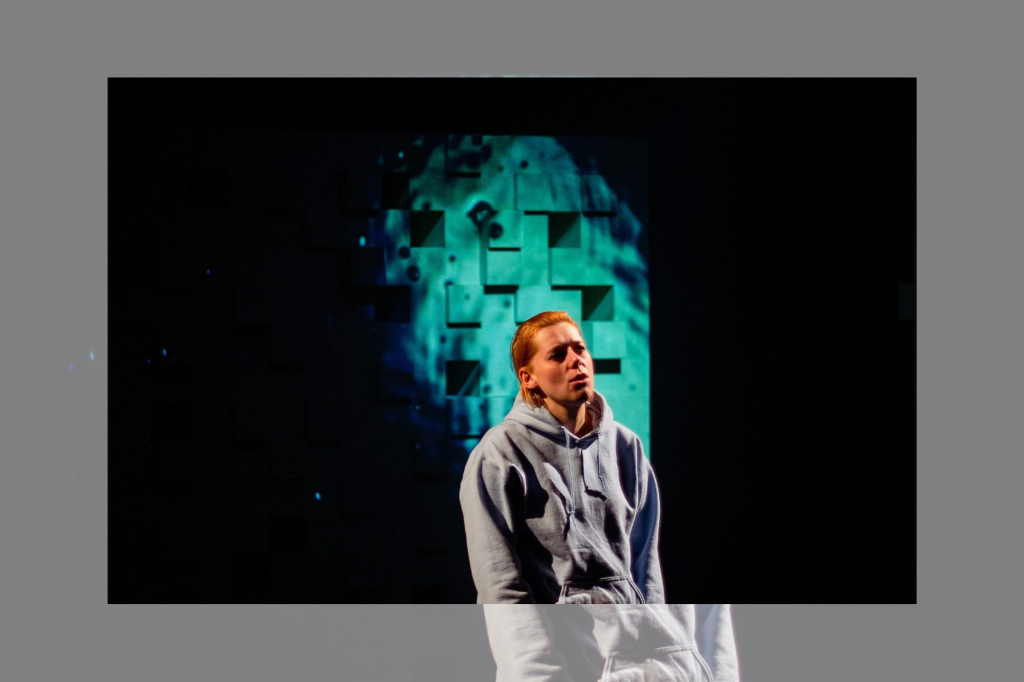

That the solo performance piece is a collaboration between a theatremaker and a visual artist is evident throughout the show. Upon entering the theatre, I was immediately captivated by the deceptively minimalist set in the middle of the space. Resembling a giant game of jenga, or perhaps a tiny Brutalist-inspired apartment complex, the mobile three-walled box creates a restrictive yet adaptable space in which Femke Stallaert, the piece’s sole performer, can play. Removable boxes jut irregularly from the surface of the structure, ready to be placed into one of the many empty cubbies that surrounded them. At a glance, the holes appear empty, but they house several secrets that are revealed as the show progresses.

Covering less than half the stage, the set is a perfect representation of the themes of grief and healing, particularly when lit – the stark contrast of the pale illuminated structure against the ominous, dark space that surrounds it is astounding. The effect of the cubbies is unsettling in certain lights, creating small, dark chasms that made me feel ever-so-slightly trypophobic.

Water is one of the recurring themes of the piece, and Abaas uses video projections that heavily feature this element. I hesitate to say that the projections steal the show, as the entire experience is a visual wonderland, but they change the atmosphere of the room. At one point, projected coins fall to the floor mere seconds before actual coins descend from the ceiling, in a moment that left me wondering if I was imagining things. Later, waves crashed and water swirls across the blocks and holes, creating an image of a barren, underwater city.

The collaborative spirit behind the production is further evident as the story unfolds: every detail is flawlessly executed, and harkens back to the script. Toronto-based theatremaker Jabr and Brussels-based visual artist Abaas have fine-tuned the visual elements of the show to tell the story almost without needing words. Combined with André du Toit’s ethereal lighting design and Arzu Saglam’s robust and precise soundscape of waves and voiceover narration, the entire experience is a sensory spectacle, but never at the expense of the story being told.

Alongside the strong impact of the visual elements, Stallaert delivers a consistently strong performance. Her presence is immense in the tiny set, and even as the walls peel away, giving her more room to play, she remains resolutely in control of every beat of the story. Alternating between complete stillness, in which only her face tells the story, and short sequences of abstract movement, Stallaert conveys a truthful story without leaning too heavily on realism. There’s a subtlety to her performance that translates well to this stage, and her proximity to the audience allows that nuance to land. Though the show almost resembles narrative theatre, Stallaert creates stakes and projects a depth of emotion that firmly centres her as a character rather than simply a narrator.

There were moments in which I found myself distracted by the sheer beauty of the visual elements of the show, but overall, it’s a well-balanced piece of theatre that feels as daring as it is lovely. Although the piece is about the experience of living within the war-machine, the themes and symbolism make it a deeply relatable piece that examines the humanity in all of us as we process grief, loss, and violence.

Broken Shapes runs November 22 through December 4, 2022 at the Theatre Centre.

Comments