REVIEW: Kooza at Cirque du Soleil

Sure, the story’s thin, the popcorn’s expensive, and your anxiety will spike watching humans plummet to near-death.

But who cares?

Kooza has all the risks and rewards for which Cirque du Soleil has become so famous, from the aptly named “Wheel of Death” to a frightening number of acrobatic feats achieved without safety nets. Countered by impish moments of clownery from some of the best in the biz, Kooza’s acrobatics and stunts are consistently impressive, a slick blend of talent and aesthetics that makes for a dazzling night under the big top in the (less dazzling) depths of Etobicoke.

By this point, Kooza’s a long-standing part of the Cirque du Soleil repertoire. Premiering in 2007 and making a stop in Toronto the same year, David Shiner’s writing and direction has since travelled the globe, landing back in the GTA now on the heels of last year’s Kurios. While the plot may leave some scratching their heads (there’s a boy in stripey pyjamas, and a human-sized dog, and a crew of Phoebe Bridgers-style skeletons), that’s sort of beside the point: Cirque du Soleil keeps audiences coming back for the adrenaline of well-executed gymnastics and the comic release of well-timed clowning, and those things are alive and well here.

The actual story, per Cirque du Soleil’s online materials: we’re looking at the world through the eyes of “The Innocent,” a young boy still figuring out how exactly the world works. While our hero flies his kite, he encounters a mysterious box which leads him down the exciting, unpredictable road of an alluring trickster.

Sure. The Innocent, played by Cédric Bélisle in those charming striped pyjamas, serves as a visual throughline, vamping with the Trickster (Mitch Wynter) in between the more gripping circus fare. Under the watch of a terrific, shimmering, two-storey bandstand (designed by Stéphane Roy), which houses the note-perfect band (led by Fritz Kraai) and serves as a portal through which the performers enter and exit the stage, we watch the Innocent grapple with the delights and terrors of this world.

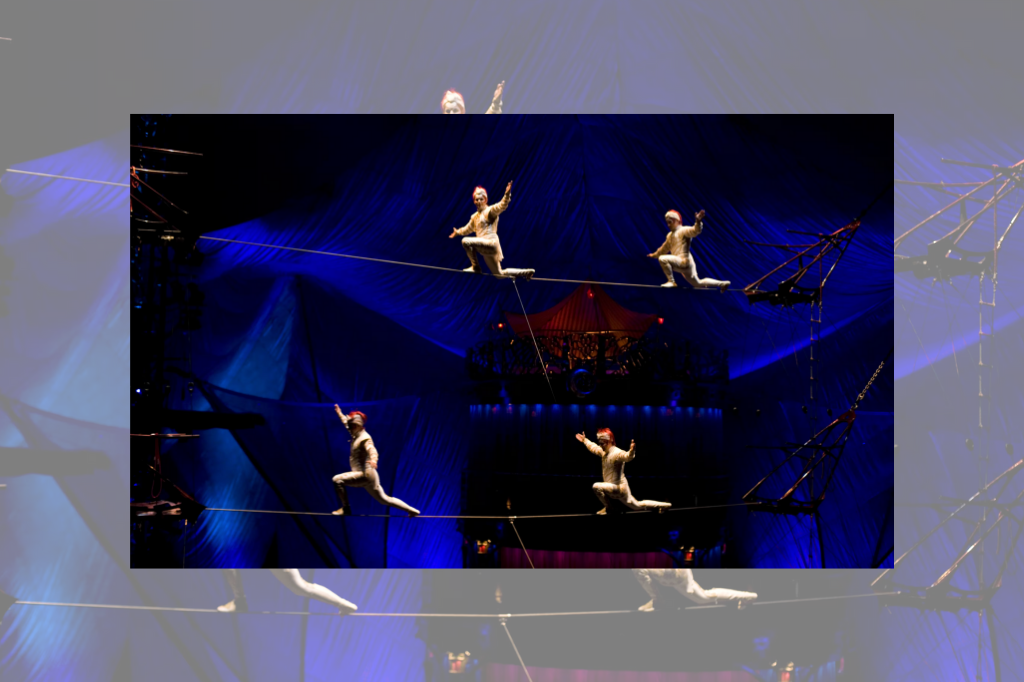

And how breathtaking those delights and terrors are: lithe contortionists in striking bodysuits. An aerial silk artist unhindered by gravity, yo-yo-ing from the tippy top of the circus tent all the way down to the ground. A group of tightrope walkers (and cyclists) teetering from one end of the stage to the next dozens of feet above the ground.

And then, of course, the Wheel of Death, a large, metal apparatus suspended in midair with freely spinning circular cages on each end. As the device rotates, so too do these cages on their own axes — the item itself is quite spectacular to behold. Then two performers, Jimmy Ibarra Zapata and Ronald Solis, occupy either end of the Wheel, leaping, somersaulting, and slithering their way in and around the machine, seemingly by magic. More than once do the men go flying, almost certain to plummet to the ground so many feet below. But every time they land perfectly, keeping the wheel spinning and ceaselessly impressing the earthlings down on the floor. Kooza has positioned the Wheel of Death as the show’s centrepiece, and with good reason: if there’s a part of the show that will inspire you to purchase a ticket to a second night, it’s this.

Jean-François Côté’s music keeps the circus flitting along smoothly, inspired by the drama and major-minor scales of Indian ragas. (Listen closely in the second act: you’ll hear “kooza” in the lyrics a few times.) Marie-Chantale Vaillancourt’s costumes, too, amp up the theatrics of the production, from slick, stunning leotards to the more playful skeleton and dog getups.

This Cirque du Soleil offering is a good one to start with if you’ve never been before: the experiential payoff makes the GTA traffic and steep price tag worth it. This is circus without any echoes of problematic freak show culture, and rather an impressive (even jaw-dropping) showcase of athletic and artistic ability.

Kooza plays at the Toronto Big Top in Etobicoke until June 18. Tickets are available here.

Comments